Movement experts are trying to change the game for people who rely on the strength and agility of their bodies for work, like Terrance Carson. Photo by Ross Hailey

Training and Technique Help Improve Performance and Stave off Injury

Professionals in dance, music and sports rely on the health and agility of their bodies to maintain long careers.

The human body is an intricate organism composed of muscle groups, bones, organs and a nervous system all working in harmony. The human body is also the source of work for dancers, athletes and musicians.

Such careers depend on the health, function and agility of the body. The professionals’ bodies are their livelihoods.

What does optimal health look like in these professionals? What happens when, not if, something goes awry? With this body work comes an entire sector of experts and researchers who focus on preventing injuries and improving performance.

“It is the oddity of each player, each dancer, each artist that makes them so good at what they’re good at,” said Michelle Tyer Heines ’91 (MFA ’96), a movement expert and strength trainer who owns Optimal Performance Group in Tyler, Texas.

Talent alone doesn’t keep athletes such as basketball player Jaedon LeDee in the game. Learning to take care of their bodies is key. Photo by Ross Hailey

No two bodies are alike, she said, and the way someone is built can make that person more likely to be talented in a particular activity.

Heines cautions athletes not to rely on talent alone. Just because someone is doing something well doesn’t mean that person is doing it “right” or in a healthy, sustainable way. She also issues a warning: “Everything done too much is an invitation to disaster.” But that’s precisely what these professionals do: A musician practices for hours, ballet dancers move through dozens of pliés and tendus at the barre, and athletes run drill after drill.

“What if at 45 minutes I’m experiencing pain? What do I do? That conversation isn’t happening,” said Kristen Queen ’19 EdD, interim director of the School of Music. “Over time, because we know this is our discipline — this is what we want to do, either right now or long term as a profession — there’s a propensity to say, ‘I will do anything I need to in order to be successful.’

“We are also saying that message to ourselves internally and so perhaps blocking out receptors saying, ‘This is good,’ ‘This is OK,’ or ‘This is painful.’ I find sometimes that students will get into patterns, and this [was] true of me when I was in college, of sort of the no pain, no gain mentality, which is, in some cases, still kind of alive and well.”

Queen, Heines and other trainers, therapists and teachers are trying to break through that mentality.

“For a person who is beating their body up every day, they come to me for managing their body,” Heines said. “I know their bodies. I see them. I memorize them.”

Heines said that when people know their bodies, they have functional movement awareness. This leads to confidence, she said, because they’re not acting based on talent but on the knowledge of how their bodies move.

Across music, dance and sports disciplines, TCU faculty and staff are encouraging students to become familiar with the intricacies of their bodies early in their careers.

Kristen Queen, interim director of TCU’s School of Music, leads the class Yoga for Musicians to encourage students to learn their bodies as much as they learn their instruments. Photo by Ross Hailey

“Nobody knows your body better than you,” said James D. Rodriguez, assistant professor of voice and voice pedagogy, clapping his hands in punctuation. “I think you develop your practices and, as you observe these practices over time, they yield the results you want.”

Queen, a 200-hour registered yoga teacher who also is part of the Performing Arts Medicine Association, developed the Yoga for Musicians class primarily to help students gain awareness of their bodies.

“Where the education is falling apart for us as performing artists is we spend so much time learning our instrument,” Queen said. “We don’t spend time learning our body.”

She suggests moving joints through their full range of motion. “In my case, if it’s a flute recital, and I just spent an hour solid playing my instrument, moving my fingers, raising my arms, what’s my recovery process look like?

“Most students don’t think about what happens afterward and how they need to take care of their bodies,” Queen said. “It’s a big area of opportunity to not only educate the students, but also educate the professors, the teachers, the people who are working with those students about changing the game.”

In the body-work professions, downtime is a luxury some don’t have. “This is all about quick,” Heines said. “Coaches want them back out there.”

Relying on larger muscle groups is one way athletes like basketball player Jaedon LeDee can prevent injury. Photo by Ross Hailey

Antidote to Injury

The pressure to perform, regardless of the risk, is ever present. If the athlete isn’t physically sound, the second string is ready to step in. Dancers have understudies. Musicians have second chairs. Someone else is learning the same plays, choreography or compositions.

Double bass players like Robert Carter can be prone to lower-back pain. Photo by Ross Hailey

Taking time out, relying on larger muscles and bones to produce force, and maintaining an aligned posture are Sajid Surve’s antidotes to injury. In addition to his practice providing care for performing artists in the Dallas-Fort Worth area, the co-director of the Texas Center for Performing Arts Health at the University of North Texas and associate professor of family medicine at UNT Health Science Center Texas College of Osteopathic Medicine brings batches of music educators to his seminars to explore solutions.

“You have to treat it like a sport, but a sport for really small muscles,” Surve said at one such seminar. Staying in optimal condition includes warmups, adequate breaks, cool-downs and cross-training. Then the body will be ready for forces, postures and repetitions that are imposed on it.

On a marker board, Surve wrote: force + posture + repetition = injury. “This is a high-risk thing,” he said. “There’s a really high likelihood that injury can occur. We have to be more mindful of what is going on. Then it’s manageable.”

Surve’s goal is to talk educators through what it looks like to create more force with less effort while maintaining optimal posture. “We want to offload tasks to the biggest muscle possible to accomplish that task,” he said. “When we play, we try to do it in a way that is using your triceps or your shoulders to protect yourself … and keep the joint as neutral as possible.”

Queen turns to yoga to understand the ways musicians use their bodies and to integrate poses that can be therapeutic for those frequently used parts. For example, she asks students to move their bodies in an opposite direction, move a joint through its full range of motion or allow stretching.

Violin and viola students who spend much of their performing time with their heads turned to the left, thus compressing that side of their neck and perhaps raising one shoulder, are encouraged to spend time moving in the opposite direction throughout their day.

“Once you start to isolate what are the muscle groups or the joints or the spaces in the body that are critical for producing the sound, those are going to be rife [with] injury, overuse or inflammation,” Queen said. “Those are the places where we can ask ourselves: Is that a part of the body that can move in a different way to help encourage circulation?”

Kristen Queen says moving through a full range of motions can help relieve the stress on muscles and joints that can come with playing an instrument. Photo by Ross Hailey

Proper Way to Practice

When physician and musician Stephen Scott was an undergraduate student majoring in piano at Rice University, he found his passion turning into pain. With a high-stakes juried piano exam weeks away, Scott felt his arms become sore and tight. His endurance in front of the keys dipped.

Students like saxophonist Jakab Macias must learn to advocate for themselves to break out of the “no pain, no gain” culture, body-work experts say. Photo by Ross Hailey

“I just overdid it,” Scott said. “It wasn’t as simple as taking a week off in the summer and, ta-da, it’s all solved. It became something that impacted that next year.”

Scott didn’t take time off to heal. Instead he carefully trudged ahead — in pain.

“I had to learn how to be smarter about my practice time,” said Scott, senior associate dean for educational affairs and accreditation at the TCU and UNTHSC School of Medicine. “I had to relearn how to practice — it’s not just playing it a thousand times, it’s focusing on the things that you need to work on and paying attention to the mechanics in a much more careful way and not going all-out all the time just because you feel like it.

“Maybe it was partly my youth, partly my inexperience or probably because I hadn’t had any limits before. I didn’t have that kind of insight about how it all works and that there are limits.”

Scott said there is a misconception that to play loud, a pianist has to push the keys harder. “The mechanics of the piano are such that when the key is depressed, once it has fallen and the hammer has left to hit the string, there’s nothing left to do.

“Continuing to push or exert any pressure is wasted energy,” Scott said. “The energy all gets transferred to the hammer, and the hammer has already struck the string.” Also, energy is related to velocity. If someone wants to make a louder sound, it’s more efficient to make a quick motion so the key falls and the hammer strikes the string with greater speed.

Body-work experts say musicians like Alphonso Rayford need to take breaks proportionate to playing time. Photo by Ross Hailey

For other musicians, the instrument itself can cause injury. Kris Chesky, professor of music in the UNT College of Music and co-director of the Texas Center for Performing Arts Health, said musicians and teachers don’t realize there can be a mismatch between the body and the instrument.

Chesky has developed and uses computer-based technology to measure biomechanical stresses generated during music performance. These data help musicians know if, when and why certain performance practices increase risk for injury. One example of his findings: A trumpet player’s embouchure changed as the intensity of the music grew. The musician was pressing the instrument into his face, and he later experienced mouth and jaw pain.

Chesky also advocates for hearing-conservation practices that include knowing how to adjust music to lower the risk for hearing loss.

Musicians have to advocate for themselves, even if it means pushback from marching band directors who think a clarinet neck strap is a visual distraction from the band’s formation or faculty who question the talent of a pianist whose fingers can’t reach all the keys, both stories from Chesky’s findings.

“The culture of not speaking up on your behalf is a real big thing,” he said. And that’s the culture he’s trying to break.

“There are kinds of social norms, attitudes, belief systems that we are challenging in some ways,” said Chesky, who has been a freelance trumpet player since 1983.

Historically, pianos weren’t designed for different hand widths, but having a more ergonomically friendly piano could mean the difference between hand pain and no hand pain. Photo by Ross Hailey

Chesky said 86 percent of UNT’s piano majors have hand pain. “The No. 1 set of factors that drive the difference between those with pain and those without are the anthropometric indices of the hand.” So UNT purchased a smaller piano.

“If I can limit those stressors while I’m practicing, I can learn to get better technique, and I can transfer that skill into the bigger piano,” said Chesky, who found reward in seeing a musician go from self-doubt to a solution.

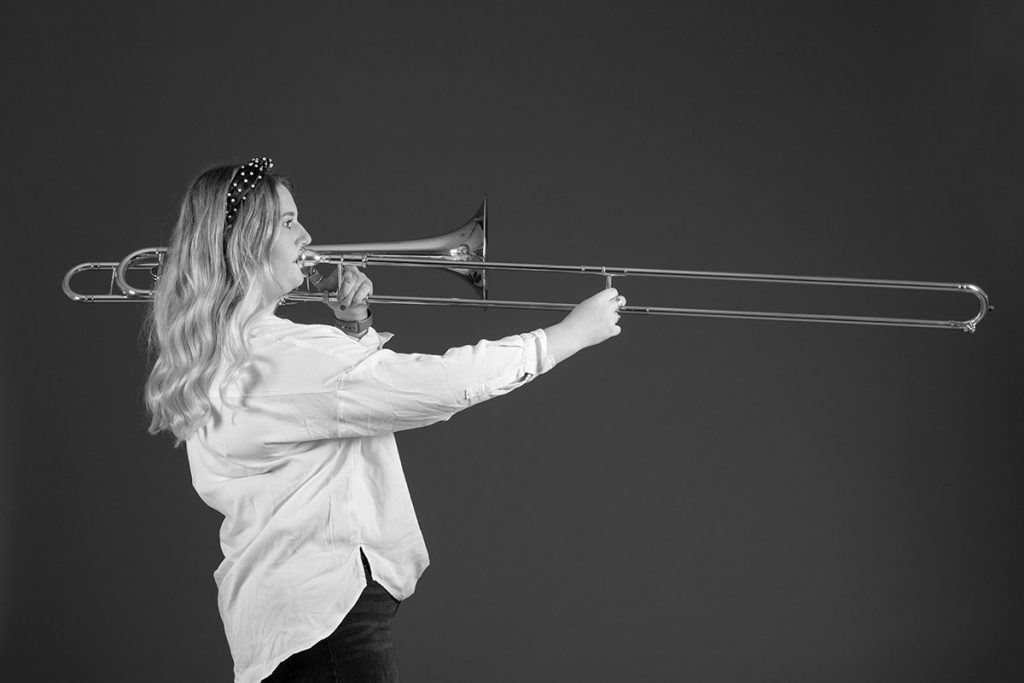

Musicians mismatched to their instruments, such as a narrow-shouldered trombonist or a pianist with small hands, Surve said, should be especially mindful of resting.

Surve asked a group of educators to consider the way a trombone rests on the shoulder and neck. He leaned forward to show the strain on the body when unaligned. To avoid this top-heavy tension, he moved his shoulder girdle directly over his hip. “Now you have built a column that you can rest on, so now your forces are coming straight down through your entire body.”

Musicians like trombonist Kaitlyn Norwood need to be aware of how their bodies are holding the weight of their instruments. Photo by Ross Hailey

When the musician is seated, the force of the body should be directed down instead of slumped forward into the instrument. Queen said students who play their instruments from a seated position, as with piano, organ and cello, complain of lower-back pain.

Musicians who play their instrument from a seated position, like cellist Manuel Papale, have to consider posture in a different way than standing musicians. Photo by Ross Hailey

“They spend so much time compressing down into their spine,” Queen said. “They’re kind of hugging around the instrument … usually curling in the spine, rather than trying to hinge at the hip to meet the instrument. It’s a ricochet effect.”

Foundation for Success

Hinging at the hip is one motion Zach Dechant looks for in his athletes. The senior assistant strength and conditioning coach with TCU Athletics works with sports players to control their pelvis and generate power from the middle. He looks at the stability of the pelvis and spine during his foundation program to analyze the five key movements: squat, hip hinge, upper-body pull, upper-body push and stability of the core sequence.

Dechant is the author of Movement Over Maxes: Developing the Foundation for Baseball Performance (independently published, 2018), which has become a manual of sorts for high school coaches. He said he wrote the book because coaches were contacting him about workouts for their athletes.

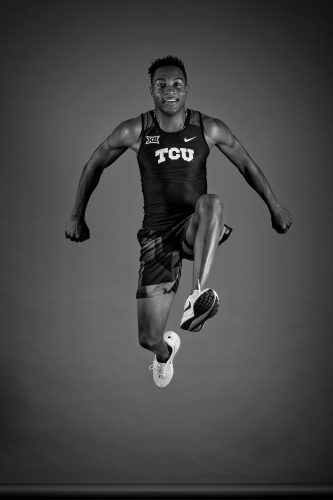

Teaching athletes like triple jumper Chengetayi “Du” Mapaya to move correctly helps prevent injury. Photo by Ross Hailey

“I said, ‘Well, if they don’t move correctly in the first place, all you’re doing is putting them in harm’s way. They’re just going to get hurt because they don’t move right.’ It’s really delayed gratification,” Dechant said. “If we handle our business up front, then we have exponential gain on the back end. But if we don’t and allow them to skip through steps in building their patterns, in building efficient movement, then we have to regress, and we’ll never be able to make the gains we could have.”

Dechant runs all his incoming collegiate athletes through a monthlong foundation program before they ever step foot on a court or field. He also screens them with the Selective Functional Movement Assessment to get an idea of how they move. If their high schools didn’t have physical therapists and movement coordinators, it’s Dechant’s job to instill new behaviors.

He used an analogy of a car with uneven tire wear. The problem isn’t the tires, Dechant said, but the alignment. “The same thing happens in athletes: They move incorrectly. They compensate for a lack of mobility or a lack of being taught the right skill.

“The body will always find a way to do a task that it is asked,” Dechant said. “The body is the ultimate compensator. It will always find a way.”

Heines, who works with MLB and NFL athletes, focuses on identifying and strengthening pelvic floor stability. Her technique draws upon her background in modern dance and movement therapy (such as the Pilates and Gyrotonic methods) to work with athletes in the performance and recovery process.

Paying special attention to stretching, nutrition and sleep and eliminating stressors helps athletes like track runner Derrick Mokaleng avoid injury. Photo by Ross Hailey

She also knows what it’s like to be in pain: She has a rare muscle disorder called McArdle disease that causes muscle contracture and fatigue.

TCU faculty members urge students, including double bassist Chengjin Tian, to spend time learning about their bodies as well as their instruments. Photo by Ross Hailey

Instead of the “bigger, faster, stronger” approach, Heines uses her own method: Athletic Stability Management. “The goal is to improve structure, build stability, prevent injury and ensure longevity through movement.”

When the focus is on the efficiency of movement, she said, there is a reduction in the chance of injury. “If muscles are what it takes to do your sport or your art, why aren’t we taking better care of them? It’s really that simple.”

As a vocalist, Rodriguez also looks for warning signs of imminent injury. “In conversations that I’ve had either with young professionals or even some of our students, we think of the voice as just the voice — the larynx, the voice box.

“We fail to see that it’s really an entire-body thing. It’s an athletic event,” Rodriguez said. “If we are to be successful and have longevity, then we really have to know how the voice functions beyond the larynx, and that means the whole body.”

The influences of posture, breathing and voice overuse or misuse are just as critical as the movement of the larynx and the sound it produces.

“The demands of the field — if you really are living, breathing, performing — it can take a toll on the body,” he said. “If your posture is poor, if your breathing is poor, all those things take a toll on the end product.”

Instead of just focusing on injury, Rodriguez said, studying the optimal body is crucial. “The more you can understand how it all functions, how it all works together, then you allow the voice to do its job. You allow it to be free of any outside manipulations in the body — whether it be posture, breath — so that it functions optimally.”

James D. Rodriguez, baritone and assistant professor of voice and voice pedagogy, says understanding how the body functions helps vocalists have long careers. Photo by Ross Hailey

His goal is for students to leave TCU singing healthily and for a long time.

Rodriguez also oversees the John Large Vocal Arts Laboratory, where he and students can record and analyze sound and use a spirometer to measure breath pressure, an indicator of lung capacity. He said acting and music theatre students in the university’s theatre department also benefit from this research into vocal health.

As with any physical feat, exercising and training are imperative for vocal athletes, Chris Watts said. “If you have not done a vocal task before that’s going to require endurance, you need to exercise those muscles to build up the ability to do that.”

Exercising a part of the body that is not visible without an endoscopic camera seems arduous (people don’t develop six-packs through their necks), said Watts, dean of the Harris College of Nursing & Health Sciences and professor of communication sciences and disorders. But ears instead of eyes recognize this practice.

“We know what the end result of using all these muscles together is: It’s sound,” he said. “We use sound as the auditory feedback, a cue to guide our exercises.”

Reps and sets aren’t just for the gym; they also play a role in Watts’ profession of healing the voice. Making low-intensity sounds is the first step. Then, as function increases, so can the frequency of the sound and reps and sets, just as someone would graduate to a heavier dumbbell.

“Most singers have had some training, and they exercise all the time,” Watts said. “The best golfers in the world go to the driving range and practice. They’re exercising the muscles that are used to do their sport or performance. The same is true for the voice.”

Warming up is another key component of good vocal health. Increasing blood flow to the muscles brings in greater oxygen for them to function in a healthier way. “The vocal folds are designed to withstand a certain amount of collision in every person,” Watts said. “They are colliding hundreds of thousands of times a day when you talk.”

Vocal folds, also called vocal cords, are also colliding, or phonating, during a cough, throat-clearing or grunt.

Preparing the Whole Self

As Scott was finishing his undergraduate degree, he did a semester of independent study to look at the impact of performing injuries on pianists. Each self-selected participant in the group of aspiring professional musicians had a story to tell about injury.

Hours of repetitive practice can pose a risk for athletes like gymnast Abbie Moore. Photo by Ross Hailey

“I would have the hunch that almost anyone who has had to do something at a very high level encounters that limit,” Scott said. “They tiptoe or cross over the line of what’s really reasonable to ask of their body and what it can do.”

There will be casualties.

“For every gold medalist in the 400-meter race at the Olympics, there are probably thousands who didn’t make it, but among those a pretty healthy number who could have,” Scott said. “But they had that career-ending injury or test with the limits and lost.”

But with musicians, dancers and athletes, the end of their careers — and their livelihoods — can come with the snap of a tendon or break of a bone. Considering the hazards of those occupations — the repetition, the leaping, the tackling, the falling — that’s an all-too-real possibility. Lack of longevity is a pain point for many careers.

In 2017, the most common retirement age was 62, reports the Federal Reserve’s 2017 survey of household economics and decision-making. The average career length for players in the NFL is 3.3 years. NBA careers average 4.5 years. The aDvANCE Project survey results found that the average age that dancers in Australia, Switzerland and the U.S. stopped performing was a little under 34.

Frequent leaping and falling can take a toll on dancers like Lauren Huynh. Photo by Ross Hailey

“Any of these folks who do things at such a high level — musicians or ballet dancers and other performing artists — that thing becomes such a core part of who they are, a part of their identity,” Scott said. “To think about that identity having to change is incredibly hard, incredibly sad and threatening.

“It’s not just about the pain in your tendon — it’s all the way to your soul. It can spark a crisis of identity.”

To add to the complexity, Dechant said, bodies are more than movement. It’s important to consider diet, sleep and stressors such as relationships and academics. Athletes are more susceptible to injuries during high-stress academic periods (midterms and finals, especially) than any other time.

It’s not a matter of leaving outside problems at the door. “If you try to separate the physical body from those things, it’s not possible,” said Laura Barbee ’06, adjunct faculty in classical and contemporary dance. “We’re trying to look at the whole body.

“Sometimes I’ll say before we start a combination: ‘Prepare your whole self. Here we go.’ It’s not about just getting your feet in the right position; you have to be completely present because you’re sharing ideas,” she said. “Maybe it’s more like poetry for some people. Using your imagination is a big part of dance.”

Sarah Newton, instructor of dance, recognizes the mix of artistry and biomechanics. “I talk about that a lot in my education course: trying to have whole-person education — W-H-O-L-E,” she said. “And how do you bring that in your performance? … You’re cognitively engaged, physically engaged, affectively engaged.”

Newton encourages students to connect to their personal experiences. In one session, she was explaining softening the chest to move through the spine for mobility and pliability. She used the memory of putting her baby on her chest for the first time and the way her body softened for her child to rest.

“Having those kinds of things to connect to is helpful,” Newton said. “You’re a person in the world. Bring your person experiences into class. Bring your person experiences on the stage.”

Thinking of the body as a whole entity, rather than multiple parts, helps athletes like gymnast Abbie Moore better prepare for their sport. Photo by Ross Hailey

Barbee, who is a certified Gyrotonic and Gyrokinesis trainer, said having endurance in focus is essential. “Being able to run a mental marathon is hard, and you have to practice it.”

Barbee teaches through these elements: movement, breath, rhythm and detail. All have to be functioning well or the other components will suffer. She uses this same philosophy for all the ages she teaches, from 4-year-olds to college students.

Understanding that stress contributes to injury helps athletes like dancer Terrance Carson stay healthy. Photo by Ross Hailey

“They’re going to change so much, so I’m giving them a good foundation so that they’re healthy from the start instead of thinking they’ll figure it out when they’re older. No, let’s teach them accurately from the beginning,” she said.

There’s a balance between what the body was born with and what the body is capable of. Dechant identifies three reasons a body may not move well. First is anatomical — this includes all the genetic factors that determined how the body was formed. Next is motor control — the motion is available, but the brain doesn’t realize it. The third is a length-tension relationship problem — difficulty with flexibility or mobility.

Newton teaches students how to consider anatomical factors while in motion. Her Functional Anatomy for dancers course, co-taught with biology instructor Molli Crenshaw ’09 MS, includes a generalized look at the anatomy of the body and how it’s applicable to dance.

A central question of the course — How can deeper understanding of individual anatomy equip a dancer with the tools to work optimally in class and performance? — is explored in movement labs.

After a lecture on bones in the foot, Newton said to illustrate, students pair up and are “palpating the different bones of the foot, feeling for the bony landmarks, noticing how the joints articulate with one another and move.”

Students would then analyze the ankle’s range of motion, discuss possible causes for limitations and relate it back to dance movements.

Recognizing anatomical markers — such as tibial torsion (twisting of the shin bones), uneven leg length, sideways curvature of the spine — leads to an understanding of how to work optimally within the form.

“You don’t have to have a perfect body to be an amazing dancer,” said Deborah Vogel, adjunct dance faculty and co-founder of the Center for Dance Medicine in New York City. “The body is actually designed to move. When we have efficient alignment — anatomical alignment — when we’re aligned well, our muscles then can work in a balanced fashion.”

Dancers like Lauren Huynh, front, and Abby Linnabary rely on cool-down time to recharge for the next performance. Photo by Ross Hailey

Through animated lectures, Vogel teaches students to understand the relationships among parts of the body. Tightness in the hips, for example, can influence how the knees and ankles work.

Neuromuscular patterning between the body and the brain can form by just thinking through the motions. The body-brain connection includes emotions that are chemicals flowing through the body. Instead of “mind over matter,” Vogel said, it’s “mind with matter.”

“When you have something that you’re passionate about and you hit a block, get a bad grade or doubt yourself, this is where we get to do the real-life work,” she said. “How can I bring myself back on course? That maturation process happens on a daily basis.”

Vogel’s students do “a full physical exploration” through stretches and strengtheners to become more somatically aware of where their body is in space and how their feet feel on the ground.

“Whatever the intellectual information is, I want to get it into their body,” she said. “Perfection is a good goal to have as long as you realize that it’s the process — that getting to it — is important. …

“The body is the vehicle for life,” Vogel said. “Listen to the messages that your body is giving you. And then be curious.”

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related reading:

Research + Discovery

Germán Gutiérrez Believes in the Power of Music

The director of orchestras at TCU says music is a way for people to work together and put aside political differences.

Alumni

Tina Mullone Choreographs a Dance Career

MFA grad never stops moving as she leaps from ballet to modern to more

Research + Discovery

Making the Mind-Body Connection in Dance

Jessica Zeller values student input and critical thinking over rote mimicry.