Making a Difference Through Medical Nonprofits

Four alumni physicians have a heart for healing and work to make the world a better place — one patient at a time.

Trudging through a dark wooded area to deliver medical aid to a homeless person is no glamorous task. Training a team to test children’s blood sugar at midnight is no easy feat. And these physicians’ day jobs aren’t any easier.

Four physicians, all TCU alumni, have identified health care needs in their underserved communities and, in some cases, across the globe, and they are working to lessen human suffering through medical nonprofits.

The physicians share a drive to use their skills beyond their day jobs. Each practices a different medical specialty with even more distinct extracurricular paths.

From caring for homeless people and the uninsured to providing forms of escape and camaraderie for chronically ill children, these physicians are shining a light on the neglected corners of medical care and keeping their fingers on the pulse of health care advocacy.

Dr. Brandon Pomeroy ’88

TCU Major: Chemistry

Medical Specialty: Urology

The Nonprofits: Care Beyond the Boulevard and Medical Missions Foundation

A patient clutches his medicine refills at the Care Beyond the Boulevard clinic in Kansas City. Photo by Shane Keyser

August 2018 — Nestled among faded Victorian and American Foursquare houses in Kansas City, Missouri, stands the Independence Boulevard Christian Church. Before Dr. Brandon Pomeroy reaches the back door of the dome-topped church, a woman stops him.

“Oh! Doctor,” she says before explaining that she can’t get her prescription because the pharmacy doesn’t have her address and contact information. The pharmacy needs a physician to resend the order.

“I’d be happy to do it,” says Pomeroy, a physician for Kansas City Urology Care. “We’ll get it to you.”

Inside the church on Gladstone Boulevard, Pomeroy greets the triage team of Care Beyond the Boulevard.

The nonprofit organization, started by Jaynell “KK” Assmann, provides medical and mental health care to the city’s homeless and underserved populations.

George holds out his arm as Dr. Brandon Pomeroy uses the flashlight on his phone to inspect a rash at the Care Beyond the Boulevard clinic. Photo by Shane Keyser

Before creating Care Beyond the Boulevard, Assmann, a nurse practitioner, volunteered at the Micah Ministry. That organization helps impoverished people by providing services such as Monday night meals that can draw as many as 700 people.

As Assmann served plates of food, people started telling her about their ailments. “A meal a week is great, but they need more than that,” she said.

In March 2016, Assmann launched Care Beyond the Boulevard. Within months of the clinic’s opening, Pomeroy started volunteering with her.

Assmann and the urologist share a propensity for helping impoverished people. “He and I have a little secret,” she said. “Our patients do more for us than we do for them.”

Serving homeless people gives Pomeroy a chance to grow as a physician. “The more you do that’s creative and outside your comfort zone, the better,” he said. “It makes it easier for something else. If you’ve done something like that here, or Uganda, or Mali, then you know it can be done, and you can take care of it somewhere else.”

August 2018 — On a Monday night at the church, more than 300 people eat and mingle along a dozen rows of tables adorned with plastic red-checkered tablecloths.

Within the cacophony of activity, there is order: Volunteers serve beef stroganoff and blue-iced sugar cookies and hand out bags of clothing.

If people need to see a physician, they go upstairs. Pomeroy says many patients come in for diabetes and blood pressure maintenance, bug bites, small infections and wounds, as well as psychiatric needs. He also sees trench foot and frostbite during inclement weather.

Tonight, Pomeroy is stationed in “the good room” (it’s spacious) containing a painting of Jesus, a shopping cart, a U.S. flag, a wheelchair and an artificial ficus tree. His backpack sits on a carpet of indeterminable color (maybe it’s maroon; maybe it’s brown).

Dr. Brandon Pomeroy fills out a label on a prescription bottle as nurse Kay Johnston counts pills. Photo by Shane Keyser

A woman wearing a Reba McEntire T-shirt shuffles in. “How are you doing, young man?” she asks the physician in a raspy voice. The woman, Louisa, talks to Pomeroy about back and leg pain that prevents her from sleeping through the night.

With a bedside manner honed over two decades of medical practice, Pomeroy asks questions about the nature of her pain. He makes notes on a sheet of paper.

“We have the same birthday,” Pomeroy says.

“Oh, awesome,” Louisa says. “We’re awesome. We’re twins, you know. Geminis are twins.”

Pomeroy takes out his stethoscope and listens to Louisa’s lungs. He leaves the room to get her naproxen and Imodium. (“We don’t have any narcotics,” Pomeroy says. “Especially on the streets, it’s important not to have that stuff.”)

Across the hall, next to a church organ, a portable wooden case holds clear bins of prescription medications.

Billie Jean has come to the church to talk about swelling in her legs. “I haven’t had very much sleep since it’s been raining,” she says. “Everything of ours is wet.” She says she doesn’t have a tarp for her tent, nor does she have poles. The tent is attached to a tree.

Billie Jean pushes her curly auburn hair out of her face to look down at her feet. She says she frequents QuikTrip for hotdogs and buffalo chicken. “Salt makes you swell,” Pomeroy says.

A convenient, sodium-laden diet like Billie Jean’s is not uncommon for homeless people. In studies assessing the nutritional status of homeless adults, many researchers have noted the population’s levels of malnourishment from inadequate diets. A qualitative study from the United Kingdom published in Nutrition Research Reviews found that homeless people aspire to eat more fruits and vegetables but are limited by low income and lack of storage for raw and perishable food.

Dr. Brandon Pomeroy, center, discusses a prescription with Richard, left, while nurse Brian Ghafari delivers an additional medication. Photo by Shane Keyser

Within five months of starting her health care initiative, Assmann realized her medical efforts to help the homeless still weren’t enough. It’s difficult for homeless patients to make their health a priority when they’re struggling to find their next meal and somewhere to sleep, she said. They are reluctant to leave their tents unattended and risk theft of their belongings. And, she said, “the bus system is not easy, particularly if you’re carrying your house on your back.”

In September 2016, Assmann launched a medical group to take health care directly to homeless people living on the street, with Pomeroy joining the crew.

“Worrying about getting to the pharmacy to pick up your prescription is really low down on the totem pole,” the nurse practitioner said. The portable pharmacy, with donated supplies, accompanies the church clinic and street medicine group.

* * * * *

In November 2011, Pomeroy drove a nun to an advocacy event in Wichita, Kansas. The physician expressed his desire to participate in a medical ministry in Africa; he just couldn’t figure out how to get there. The nun told him not to worry and that she would pray for him.

Two weeks later, Pomeroy received an email addressed to all Kansas City urologists.

The group email was a plea to help a 12-year-old Malian girl (the same age as his own daughter at the time) with an ectopic ureter. Ureters are tubes that connect the kidneys to the bladder. But one of the girl’s ureters bypassed her bladder and connected to her vagina, causing her to constantly leak urine.

Dr. Brandon Pomeroy, right, said his homeless patients come to the clinic with a variety of ailments, including those related to their lack of permanent shelter. Photo by Shane Keyser

“I saw that [email] and I said, ‘Yep! I don’t even know where Mali is — I’ve never heard of it — but I’m going.’ ” After Pomeroy performed the surgery, the girl was able to go to school. “That’s a big, life-changing thing,” he said.

In 2018, Pomeroy used almost all five weeks of his vacation time on international medical trips. “I feel a responsibility,” he said. “It’s just the usual cliche thing: If you’re good at something or if you have a passion for something, you kind of have a responsibility to not just go to the lake. You should help people if you can.”

Pomeroy has traveled to Uganda, Mali and India multiple times through the Medical Missions Foundation, a nonprofit organization that sends teams of doctors and nurses to underserved communities around the world.

“It’s important to go there and pay attention, to learn from them and pay attention to the way they do things and what their actual needs are,” he said. “As long as there is a need, you can keep evolving what you do there to make it more useful to the people there.”

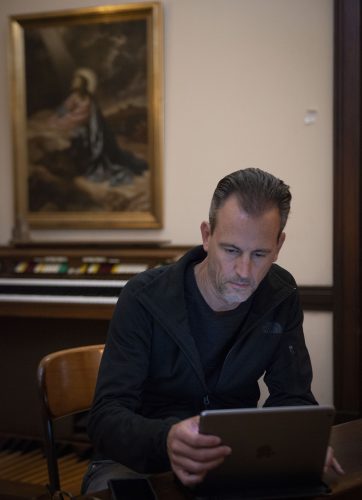

Dr. Brandon Pomeroy uses an iPad to fill in patient information for the Care Beyond the Boulevard clinic at Independence Boulevard Christian Church. Photo by Shane Keyser

During a weeklong stay in India in February 2019, the urologist performed 55 surgeries, working from 8 a.m. until 8 or 9 p.m.

Instead of an “operate and leave” model, Pomeroy prefers to teach physicians in countries where there may be limited education and specialty training. He is sometimes a medical student’s only exposure to urology. “I’ll be operating and there will be 15 medical students in the room with me watching,” he said. “I’m their whole urology rotation.”

Instead of swooping in with elaborate, high-tech instruments that will be loaded back on an airplane after a week, Pomeroy shows doctors abroad how to use the instruments they have. “The most useful things are a little bit beyond what they can do there,” Pomeroy said. “You don’t want to go in and do stuff they can’t do. You want to teach. These are good doctors that are there.”

Pomeroy stepped up to lead a September 2018 mission trip to Uganda. He has since headed another team. “All these African countries had a lot of bad things happen over the last hundred years,” Pomeroy said, straightening his copy of The Teeth May Smile but the Heart Does Not Forget: Murder and Memory in Uganda by Andrew Rice (Picador, 2010) on a table, exposing the “be kind” tattoo on his right forearm and the sacred Hindu om symbol on his left wrist.

“You see how small the world is. You see how people are the same everywhere,” he said. “You come back, and you share it with people. You’re a better person, maybe, a more tolerant or patient person, and that rubs off on other people. You’re spreading these little oases of kindness.”

Dr. Wendy Heger Bonnell ’95

TCU Major: Neuroscience

Medical Specialty: Pediatrics

The Nonprofit: Ruth’s Place Clinic

The single-wide trailer that once housed Ruth’s Place Clinic’s medical practice is now used as a food pantry and for English as a Second Language classes and other services. Photo courtesy of Ruth’s Place Clinic

Past propane businesses and gun shops sits Ruth’s Place Clinic. Dr. Wendy Bonnell has been part of the clinic in Granbury, Texas, since its second inception.

The founding organization closed the clinic after deciding to withdraw from the health care field. In 2009, two of the original leaders asked Bonnell and her husband, Ric, both pediatricians, to help restart the medical service and work as physicians at the clinic.

“We were both on board right away,” Bonnell said. “I think from the time they talked to us until we opened our doors was only a few weeks. They were ready.”

The re-established free clinic operated out of a single-wide trailer in Oak Trail Shores, an unincorporated community. Benefactors later purchased a more central location in town on Crawford Avenue and sold it to the nonprofit for $1.

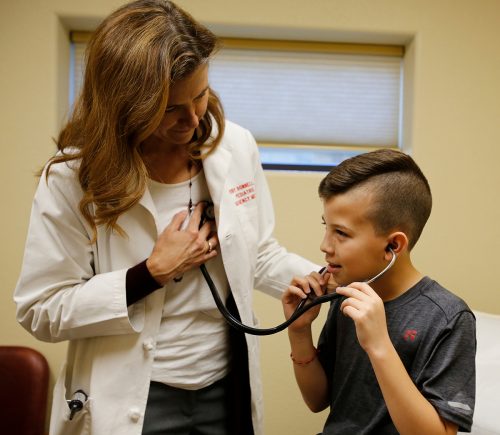

Dr. Wendy Bonnell lets Mauricio listen to her heart at Ruth’s Place Clinic in Granbury, Texas. Mauricio is interested in being a physician. Photo by Ross Hailey

Even though practicing medicine in the trailer was challenging, Bonnell said, it proved insightful. Medicine today focuses more on social determinants of health.

“Working in that single-wide trailer was a perfect example of that,” she said. “You get to know the patients that much better when you know where they’re coming from and what they’re going back to.”

Healthy People 2020, the nation’s 10-year goals and objectives for health promotion and disease prevention set by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, identified five key areas of “place-based” social determinants of health. They are economic stability, education, social and community context, health and health care, and neighborhood and built environment.

With this place-based perspective, Bonnell considers factors such as lack of transportation as an obstacle to obtaining prescriptions or the challenge of treating head lice on a patient who shares a room with four siblings.

An aerial view of Ruth’s Place Clinic in Granbury, Texas, shows the donated metal structure that was added onto the original brick house. Photo by Ross Hailey

“For me, I had always practiced in an emergency room setting, in kind of a social bubble,” Bonnell said. “I knew that my patients struggled with other aspects of health that kept them from accessing it. I don’t think I fully understood that until working at Ruth’s Place that first year.”

The U.S. Census Bureau estimates that 7.9 percent of residents under age 65 in Hood County, Texas — where Ruth’s Place is located — did not have health insurance in 2016. In 2017, about 10.6 percent of the population was below the poverty line.

Bonnell treats two to 15 patients in an average day but never the 40 patients a day she would treat at a regular pediatrician’s office. Many of her patients have fallen off Medicaid for a short time, she said, and she sees them in that gap period as they work to get back in the system. Some patients have insurance but do not have access to health care.

Dr. Wendy Bonnell works as a physician at Ruth’s Place Clinic, a nonprofit that provides free care for families in need in Granbury, Texas. Photo by Ross Hailey

Navigating the labyrinth of health care is important for Bonnell, who wears the hats of both physician and social worker. She said she spends half of the time treating patients and the other half asking questions about their social circumstances and determining how the clinic can access the appropriate treatment for them.

In 2012, Ruth’s Place converted the building’s garage into a dental clinic. The house is connected to a 3,200-square-foot addition donated by Mueller Inc. as part of its Helping Hand Project in collaboration with the television show Texas Country Reporter.

The Oak Trail Shores location is still used for a food pantry, an after-school program, English as a Second Language classes and parenting programs. The nonprofit even hosted a mechanic to fix cars.

If someone has an idea to help others, “we’ll figure out how to do it,” Bonnell said. “Just providing medicine itself isn’t always going to be effective without addressing everything else.”

Despite the challenges of working through patients’ socioeconomic statuses, there is an element of freedom in practicing medicine at a free clinic. No one tells Bonnell which prescriptions to push, and there are no third-party payers to deal with or emphasis on running a business with an impractical patient quota.

Dr. Wendy Bonnell examines Gypsy at Ruth’s Place Clinic. Bonnell treats two to 15 patients on an average day. Photo by Ross Hailey

October 2018 — At the clinic, in a room with a Goodnight Moon print on the wall, Bonnell asks a young girl named Gypsy if she knows the location of her heart. The pediatrician lets the girl wear her stethoscope and applies the chest-piece to her heart.

“She was born at 25 weeks,” Gypsy’s mom, Katie Hott, says. “She spent her first 104 days in the hospital.”

Gypsy’s brother Shelton, dressed in a red Spider-Man shirt and Spider-Man shoes, asks for a turn. “Come on, Spider-Man,” Bonnell says, lifting him onto the exam table. “Where’s your heart?” Bonnell helps him listen to his heartbeat, too.

Dr. Wendy Bonnell listens to Shelton’s heart during a physical at Ruth’s Place Clinic. Photo by Ross Hailey

After the exam, Bonnell leaves the room to check her chart for her next patient, her heels clicking down the corridor. The physician says she used to come to the clinic in flip-flops and a ponytail, but Dr. Romeo Bachand, the clinic’s medical director, encouraged the team to show patients the same amount of professionalism as in a mainstream hospital.

“Every Thursday do I want to necessarily get up and get dressed and go to Ruth’s Place and have a million other things to do? I don’t. But it’s a great reminder for me: I’m always happy once I step foot in the door,” Bonnell says. “By the time I leave, I’m always crazy happy because I know it’s what I’m supposed to be doing.”

Dr. Alison Hartman Lunsford ’03

TCU Major: Biology

Medical Specialty: Pediatric Endocrinology

The Nonprofit: Diabetes Foundation of the High Plains

Taygen lost 10 pounds in four days when he was 8 years old.

His mom, Randi Armstrong, carried him into a hospital in Amarillo, Texas. With his weight at 42 pounds, she said, she could count her son’s ribs connecting to his sternum.

“I thought he was going to die,” Armstrong said. “I really did.”

A woman at the entrance of the hospital identified Taygen as diabetic. She led them to the strollers and walked with them to the pediatric intensive care unit. A normal blood sugar level for an 8-year-old is between 70 and 150 milligrams per deciliter. Taygen’s blood sugar that day was 946 mg/dL.

A few days after diagnosis, Armstrong asked hospital employees about the greeter and described her. Nobody had heard of her. “My husband and I are convinced that God had put an angel in there. God knew how sick he was so the angel could show us where to go,” Armstrong said. “We literally had an angel take us to the PICU.”

Taygen, now 10, said he doesn’t remember much surrounding his diagnosis and hospital stay, but the medical team gave the family a crash course in Type 1 diabetes. The team also invited the boy to Camp New Day, hosted by the Amarillo-based Diabetes Foundation of the High Plains.

At the camp, children living in West Texas and eastern New Mexico learn to manage their chronic illness better and have the opportunity to do typical summer camp activities: swimming, hiking, arts and crafts.

Dr. Alison Lunsford, a pediatric endocrinologist, heads the Diabetes Foundation of the High Plains in Amarillo, Texas. Photo by Ralph Duke

Dr. Alison Lunsford, a pediatric endocrinologist in Amarillo, heads the diabetes foundation and was one of its founders. She was a year into her medical position at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center when a group of her patients’ parents approached her about funds they had raised and their desire to keep the money local. They met in Lunsford’s living room and outlined the foundation.

“Had these parents not approached me, and the right people and the right time and the right money come together at the same time, I don’t think I would have ever just started it willy-nilly, especially being new to this community,” said Lunsford, who is also an assistant professor of pediatric endocrinology at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center at Amarillo.

Community members rallied to create the foundation, she said. Local lawyers help set up the nonprofit pro bono. The Will Rogers Range Riders, a club that spearheads charitable activities for the Texas Panhandle, was an important catalyst. Rhonda McDavid, the executive director of the Southeastern Diabetes Education Services, served as Lunsford’s mentor.

One key point for the foundation was to financially support an ongoing diabetes camp and to provide scholarships for the children, as well as insurance and personnel.

In her volunteer position as president of the foundation, Lunsford champions fundraising, leads public engagements and runs Camp New Day.

Campers at Camp New Day enjoy camaraderie with other children coping with diabetes, as well as counselors (including Christian Clay on piggyback, far right, back row) who assist with medical needs. Courtesy of Alison Lunsford/Diabetes Foundation of the High Plains

Armstrong opposed sending her son to the camp at first. “I just said, ‘No. No, we’re not doing it. Three days ago I thought my son was going to die, so no, you can’t take my son for a week.’ ” But Armstrong changed her mind; she realized staff members at Camp New Day had decades of experience with the chronic illness versus the short time she had managed Taygen’s diabetes. “We knew very little at that point in time,” she said. “We were leaving him with counselors and staff who know the disease inside and out.”

At camp, “it was really cool whenever you’re with everybody who understands,” Taygen said. “No one treats you like you’re not normal.”

Christian Clay, a camper-turned-counselor, said his mom and doctor talked him into going to the children’s camp. “I say ‘talked me into it,’ but I got volun-told to go,” he said.

Clay, who was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes in 2011, has attended camp seven times so far. “I enjoy the happiness I can feel from camp — being able to get out of my environment and learn something new and get to see some of my friends.”

Camp volunteering is tiring, Clay said, but helping others with diabetes is worthwhile. “Some people call it a disease; I call it a challenge,” he said. “I can show them I have the same challenge they do, and it does get easier over time.”

At the end of 2018, the Crouch Foundation of Amarillo donated a 640-acre ranch bordering Palo Duro Canyon and $500,000 to the Diabetes Foundation of the High Plains. In Ann Crouch’s handwritten will, she wanted to honor her son and husband, who both died of complications from diabetes. Lunsford said the nonprofit will design a new facility specifically for medical and special needs camps.

“I’m really excited,” Lunsford said. “We always dreamed of being able to build something.”

Dr. Alison Lunsford talks to a patient’s mother about blood sugar levels. Photo by Ralph Duke

Lunsford said it will be a lot of work, but with the help of skilled community members, she hopes the camp will be fully operational in two or three years.

Parents involved in the foundation care more about helping everyone versus the “What can you do for my kid?” mentality, she said.

“It makes it easier for me to do my job and to help take care of these kids,” Lunsford said. “We’ve been able to see a whole lot of great development in the community — awareness about diabetes. We’ve been able to support these kids a whole lot more.”

Children learn to administer their first shot and change their pump site at camp. Lunsford said kids will jump out of the swimming pool to compare pump sites. “It’s like positive peer pressure.”

At camp, all children learn healthy eating habits, and the older children learn about things to consider when they’re adults, such as insurance and drinking alcohol as a diabetic.

Initial goals of the foundation were to help patients who needed supplies, guide new diagnoses and connect families.

In the five years the foundation has operated, Lunsford has doubled the number of kids who attend camp by extending and splitting age groups and providing scholarships. Hiring a psychologist and a research nurse to help with her practice were also significant milestones.

“We had a few small things that we wanted to do and see where it took us,” Lunsford said. “It’s just taken off. I didn’t really envision how successful the fundraisers have been and how much we’ve been able to accomplish. It all exceeded my expectations.”

Avery and Owen lead a horse at Camp New Day in 2018. Campers say no one stares or is treated differently when it comes to diabetes management. Courtesy of Alison Lunsford/Diabetes Foundation of the High Plains

Camp New Day, which does not turn children away based on financial need, is just one aspect of the foundation. Lunsford said the nonprofit focuses not only on children with diabetes but also on their parents. “These parents live day in and day out with exhaustion,” she said.

Events such as an evening at a trampoline park are one way for kids to connect with other kids like themselves, as well as for parents to connect with other parents dealing with the same situations. Parents need a night out just as much as the kids, Lunsford said, and they can use the opportunity to learn the ropes from one another.

The foundation hosts five or six events each year. It also helps fund a diabetes research nurse at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center and offers aid to alleviate the sudden lifestyle changes that come with a diabetes diagnosis, such as providing grocery store gift cards to offset the cost of buying different foods and gas vouchers for long drives to the hospital.

“I have patients who have to drive three or four hours one way to get here, and your lower-income families just can’t do it,” Lunsford said. “We don’t have public transport — I can’t just send you a taxi.”

“I think Dr. Lunsford is a very good role model,” Taygen said. “She’s very kind, nice and helpful.”

At Taygen’s school in White Deer, Texas, about 40 miles northeast of Amarillo, only two other students have diabetes. Classmates are wary of the Dexcom continuous glucose monitor in the boy’s arm, so they don’t roughhouse with him like they do with other kids.

“They used to treat me like everybody else, but now they act like I’m a completely different person — like I’m breakable,” said Taygen, whose confident voice started quivering until he stepped away to compose himself.

At Camp New Day, campers with diabetes like Malachi, 12, enjoy activities such as fishing, horseback riding and swimming. Courtesy of Alison Lunsford/Diabetes Foundation of the High Plains

Lunsford said children with diabetes in the Texas Panhandle are frequently the only student in their school — or whole community — to have the disease. “Kids who have chronic diseases frequently suffer from depression and social isolation,” she said. “They feel kind of ostracized or different. They start not taking care of themselves because they feel like they want to hide it.”

Facing a barrage of questions is another challenge. “A lot of our kids deal with it day in and day out at school or a friend’s birthday party,” Lunsford said. “People just look at them: ‘Why are you sticking yourself with a needle? What are you doing? I can’t believe you do that. That looks like it hurts.’

“That gets really old, so when they’re around a bunch of kids with diabetes, nobody asks those questions,” Lunsford said. “Nobody looks at you funny. Nobody says anything. For them, that’s every bit of what they need.”

Taygen uses his condition as a way to educate others. When people ask him questions, he answers. “It gives me a chance to teach someone something new.”

One day at school, Taygen noticed one of the adults was exhibiting symptoms of low blood sugar. He helped her test her levels, and he was right.

Dr. Alison Lunsford holds a fish Taygen caught at camp in 2018. Photo courtesy of Alison Lunsford/Diabetes Foundation of the High Plains

Or sometimes he jokes. Once when someone pointed at his glucose monitor, he responded: “The aliens did it.”

Though it’s constantly on their minds, for the Armstrong family, managing Taygen’s diabetes is just part of the daily routine.

Taygen’s Dexcom monitor communicates his blood sugar levels with an app his parents have on their phones. An alarm goes off if those numbers teeter out of a set range. Even with this monitor, his mother still worries, especially at night.

“I’m still waking up and checking the app,” Armstrong said. “I’ll watch trends and sit there and stay up for hours making sure he doesn’t drop. I don’t think that will ever go away.”

After senior camp, Taygen said, he wants to come back as a camp counselor. “I can interact with the kids. I can relate, so if they’re ever having trouble, I can talk to them about my experiences,” he said. “You can help them get through if they’re out there having a rough day — help them out and find the joy.”

Clearing hurdles and grappling with diabetes will always be ongoing. Now two years after his diagnosis, Taygen doesn’t let anything get in his way. He has even tested his blood atop a horse.

“I have a disease; the disease does not have me,” Taygen said. “I know that diabetes cannot stop me.”

Dr. J Mack Slaughter ’09

TCU Major: Neuroscience

Medical Specialty: Emergency Medicine

The Nonprofit: Music Meets Medicine

January 2019 — Lyrics to a catchy pop tune and instrumentals reverberate down a hospital corridor in Dallas.

Why don’t you just meet me in the middle?

I’m losing my mind just a little.

Dr. J. Mack Slaughter fist bumps with Daniel, 7, during a jam session at Children’s Medical Center in Dallas. Photo by Rodger Mallison

Dr. J Mack Slaughter, an emergency room physician with EMC of TeamHealth, plays a Taylor travel guitar alongside a young patient’s child-size hospital bed. Daniel, small and frail, is nearly swimming in a purple gown adorned with cartoon submarines and sea life.

Hannah Hankins, the boy’s nurse, finishes labeling vials of blood samples. “He’s been kind of grumpy because he hasn’t been able to eat,” she says. “This is perfect. Thank you all so much.”

Slaughter places a small electric drum set on the bed and hands Daniel the drumsticks. The boy starts tapping away. Compliments stream from Slaughter about Daniel’s prowess: “You’ve got natural rhythm, buddy.”

“Big finish!” Slaughter says in a crescendo. The duo seal the jam session with a fist bump. “Skidoosh!”

During the winter hospital visit at Children’s Medical Center Dallas, Slaughter was not on the clock. Rather, he was volunteering for Music Meets Medicine, the organization he created in 2008 that focuses on children’s hospitals in the Dallas-Fort Worth area. The nonprofit brings music to young patients with chronic illnesses using jam sessions, music lessons and financial donations.

“Through playing music for and with patients, you give them this escapism,” Slaughter said. “You give them this positive, uplifting course in the moment. Some people respond to it, and some people really respond to it.”

Dr. J Mack Slaughter is the founder of Music Meets Medicine, a nonprofit organization that donates instruments and provides music lessons to patients in children’s hospitals. Photo by Rodger Mallison

Music Meets Medicine funded a therapeutic arts room at Children’s Medical Center Dallas with Kidd’s Kids in memory of radio icon and Slaughter’s mentor Kidd Kraddick. Kidd’s Kids is another organization that focuses on aiding sick and physically challenged children.

“[Slaughter] was able to identify that need and then raise money to help patients who need a special place in the hospital that is safe, where they can go and express themselves,” said Lisa Jones, music therapist and the hospital’s therapeutic arts supervisor. “He was able to help fulfill that need.”

For Slaughter, the music therapy room, which officially opened in 2018, is important to complete the escapism. It gives the kids a chance to take a break from the challenges of treatment. “Anytime you experience it, you just know that it belongs.”

Music in hospitals has not always been welcome, Slaughter said, noting that history shows antibiotics and invasive surgeries are the favored routes. “All of those things are very necessary … but to ignore the social and the emotional aspects of being hospitalized, I think, is missing a crucial point in the healing process.”

But Slaughter said the tone is changing. “We are raised to our parents’ favorite music. We fall in love to music. People pass away, and we fall in love with certain songs,” he said. “All of our memories are so inextricably tied to all these musical memories, so why would we not also have that when we’re ill? It just makes sense.”

Slaughter’s first experience with music as escapism came during his mother’s chemotherapy treatment for stage 2 breast cancer. (She is now more than a decade into remission.)

A side effect of one infusion meant her fingers, toes and nails could turn black. To prevent this, she submerged them in ice for the duration of treatment — an hour. Constricting the blood flow to those vessels meant less of the drug would be delivered to the tips of her fingers and toes.

Ice may not sound problematic, but imagine the discomfort of the prolonged application of something frozen to a bump or bruise.

“My mom is strong-willed, and she would do it; she would just push through it,” Slaughter said. “She looked like she was in so much pain and agony, and we just hated it.”

Dr. J Mack Slaughter accompanies Daniel, 7, as he rocks out on a drum set in his hospital room. Photo by Rodger Mallison

Slaughter and his sisters got together and tried to figure out what they could do. They went back to what they had done as children.

“We got our instruments. We brought them into the room, and we played for her,” Slaughter said. “That hour flew by. It was happy and loving and exciting. She was making requests. Next thing we knew, she was done.

“It was just so powerful to me after I experienced that that I knew I had to do something with it. I just felt called to do it. I didn’t know how. I didn’t know where and when.”

Slaughter linked his new perspicacity to the challenges of engaging chronically ill youth while volunteering at Cook Children’s Health Care System in Fort Worth as a TCU student. That eureka moment was the impetus for Music Meets Medicine.

The first big donation came from a group of Dallas doctors whom Slaughter met through his medical residency at UT Southwestern Medical Center. One doctor’s wife had breast cancer. Slaughter explained his nonprofit organization and asked if he could jam with her.

“It was that same power I experienced in the room with my mom. … After [the doctors] experienced that, they said they were on board,” Slaughter said, slapping the table. “They gave me a big check.”

* * * * *

“We have a limited amount of resources that we can dedicate toward consciousness — what we’re keenly aware of at any moment,” Slaughter said. “We’re blocking out a significant portion of that. … If you can capture somebody’s consciousness and pull it over to you and what you’re doing, they can’t mentally be focused on the pain and the negative aspects of the treatment.”

Slaughter remembered an oncology patient at Children’s Medical Center Dallas with whom he had weekly jam sessions. The physician gave the boy a guitar, a mini amplifier and a set of headphones.

Uriel, 15, practices guitar in his room at Children’s Medical Center Dallas. The guitar was donated to the hospital by Music Meets Medicine, a nonprofit founded by Dr. J Mack Slaughter. Photo by Rodger Mallison

“He was getting really good at guitar,” Slaughter said. “It was becoming a part of who he was.” The boy was receiving aggressive treatment for the cancer in his leg, which eventually had to be amputated below the knee.

“The night before they amputated, his mom told us he was playing guitar all night long,” Slaughter said. “It went from giving someone escapism in the moment to teaching them how to cope on their own. That’s when you feel like you really can make a leap in music therapy — is giving them the tools.”

Jones, the music therapist, agrees. “It makes you feel good that music is being used in that way and that patients who are having such difficult times in the hospital can have that outlet.”

A strong benefit of music therapy, Slaughter said, is that it helps kids process what they’re going through, their own mortality. Though Music Meets Medicine does not tackle this, Slaughter said the organization supports those efforts.

Jones’ music therapists focus on helping children with the psychosocial ramifications of hospitalization. The team uses musical intervention activities as tools in the therapeutic process.

Lyric analysis and active music-making aid the formation of relationships and therapeutic bonds, and therapy can proceed from there.

Raymond Turner, recording studio producer at Cook Children’s, has seen Slaughter’s organization in action, including a recent visit to the neonatal intensive care unit. During that visit, Caroline Kraddick, Kidd Kraddick’s daughter and CEO of Kidd’s Kids, held and sang to babies as Slaughter accompanied her on the guitar.

“Recalibrating is the word that keeps coming back to me,” said Turner, who stayed in a neonatal intensive care unit as a premature infant. “Seeing what they were doing in that moment — they were giving something that that child could not express gratitude for. It was almost this act of grace.

“Seeing them do that and realizing it’s not about performing — it’s not about doing that so someone can clap and applaud or get kudos for, but singing to someone who will probably never know that happened,” Turner said. “[It’s] getting back to the heart of it and what music really means and its ability to, in a sense, heal.”

Looking forward to more collaborations with Slaughter, Turner said, “Just spending even a minute around him is infectious. His passion for not only music but also medicine and to bring those two together. He’s a person of integrity and someone who really seems to care about the purity of those two elements: music and medicine.”

Dr. J Mack Slaughter, center, performs some tunes with Uriel, 15, and his mother, Sara, in Uriel’s room at Children’s Medical Center in Dallas. Photo by Rodger Mallison

Down the hall from the sixth-floor family lounge at Children’s Medical Center Dallas, adjacent to the nurses station with a cupboard marked “Beads of Courage,” Slaughter initiates a new jam session with a teenager named Uriel. The 15-year-old is skilled at the guitar and readily plays for the physician.

“I’m going to lay down a beat, OK?” Slaughter starts, slapping the cajón (a box-shaped percussion instrument) he sits on. He shows Uriel how the instrument works on a four-count, and the two swap places.

“Big wheels keep on turning,” Slaughter starts into Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Sweet Home Alabama.” Uriel smacks the cajón, PICC lines dangling from his right forearm. The teenager picks up his tempo to match the song’s chorus.

Dr. J Mack Slaughter makes music with Lilianna “Lily,” 10, during a visit to Children’s Medical Center in Dallas. Photo by Rodger Mallison

Still playing, Slaughter looks at Uriel’s mother, Sara Mireles, and asks: “Quieres tocar también?” She joins in for the second chorus.

Accessibility is key for Slaughter, who holds the guitar for young or special-needs patients so they can strum. This is what he does for Lilianna “Lily,” an oncology patient hooked to an IV who watches Slaughter and Uriel’s jam session from the hallway.

“My name is J Mack,” the physician says, squatting down to Lily. “Do you like music?” He shows her how to strum the guitar. “Canción nueva para tí, para Lily,” he says before improvising a song in Spanish using Lily’s name.

Slaughter stops singing and asks 10-year-old Lily to strum. Her eyes lock on the guitar, her body relaxing as she runs her fingers over and over the strings. The patient and the physician become the sole residents in their own world.

Dr. J Mack Slaughter strums a guitar with Lilianna “Lily,” 10, as part of the physician’s visit with his nonprofit Music Meets Medicine. Photo by Rodger Mallison

Because he doesn’t know the children’s medical details, Slaughter said, he is able to focus on them as people versus patients. “To me, being sick is more than the disease itself,” he said. “The emotional aspect of being ill, the stress response that is elicited by being ill can be curbed, if not reversed, through music.”

In performing through the nonprofit, Slaughter found an unexpected outcome for himself. “It brings the heart back for me,” he said. “It centers me. It brings that pendulum back to the middle. From just intellectualizing the human condition and passing and all that stuff to emotionally experiencing things.”

Physician burnout is a challenge for many doctors, and patients can experience a similar strain. That’s where Slaughter and his organization step in.

“Instead of healing in the micro sense on a cellular level, fighting bacteria and fighting viruses and stuff like that, we’re more focused on healing the spirit — healing the soul.”

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related reading:

Alumni, Features

Asylum-Seekers Find Solace in DASH Network

The Dallas-Fort Worth nonprofit provides housing as well as support and friendship for people fleeing persecution.

Alumni, Features

Co-Founder of Calloway’s Nursery Thrives on Service

Jim Estill cultivates a life of hard work and lends his business expertise even in retirement.

Features

Physicians Find Value in Leadership Programs

Do business and leadership belong in medical school?