Asylum-Seekers Find Solace in DASH Network

The Dallas-Fort Worth nonprofit provides housing as well as support and friendship for people fleeing persecution.

Editor’s Note: Asylum-seekers most often are fleeing persecution in their native countries. Some of their names are withheld in this story to protect them as their court cases move through an immigration process that remains in flux.

On a Saturday morning in July, temperatures were in the mid-90s before noon in central Fort Worth. Volunteers with DASH Network started work early; weather forecasts predicted triple digits before sundown.

An asylum-seeker looks at the bedroom that volunteers Penny Tucker and Raphael Mukenga and more than a dozen others helped to set up through DASH Network. Photo by Joyce Marshall

Weekends are move-in days for DASH Network, a nonprofit that serves the Dallas-Fort Worth area. On this particular day, the team of committed volunteers was bigger than usual — almost 20 people.

Operating with economy, most volunteers were on their fourth trip from the moving trucks, delivering small furniture, plastic boxes, utensils and other household supplies up the stairs to a fourth-floor apartment.

With the arrival of pickup trucks carrying large furniture, including mattresses strapped down in vehicle beds, the volunteers shifted gears. The first order of business: a three-cushion cloth couch. The cumbersome frame made the green-colored sofa impossible to carry up multiple floors. Standing upright, it narrowly fit in the building’s elevator.

The two-bedroom apartment with vaulted ceilings filled up fast. The couch was set down on an area rug amid end tables, clothes and household items. Each bedroom had two beds.

The furniture and household accessories were for four people who had fled their native countries to seek asylum in the United States.

As the volunteer movers walked through the front door, they asked the first two tenants to arrive — French-speaking twin sisters — polite questions. “Quel pays?” someone asked in French, translating into “Which country?”

With the conversation going slowly, the volunteers and the sisters turned to a former DASH resident from central Africa to translate. The volunteers needed to know the sisters’ preferences for where household things should go and where to place furniture.

The summer heat was rising, and two more asylum-seekers were waiting to move in.

The Housing

In 2012, Ashley Young Freeman ’09 started DASH (DFW Asylum-Seeker Housing) Network in Fort Worth. The nonprofit differs from other Dallas-Fort Worth area organizations in that it provides housing, in addition to other services, for asylum-seekers waiting for their work permits.

Ashley Freeman is the founder of the DASH Network, a nonprofit organization in Fort Worth that houses and feeds asylum-seekers. Photo by Joyce Marshall

Asylum-seekers are not the same as refugees or migrants. Migrants move to a different country for economic reasons, while refugees and asylum-seekers have to flee for their safety. Services such as housing and resettlement aid are provided to refugees, who typically arrive in the U.S. after long waits in camps overseas. Asylum-seekers, who enter the country on their own, must find such help for themselves.

Without DASH Network in North Texas, asylum-seekers’ “only option was the homeless shelters, which were very dangerous places and not a program tailored to asylum-seekers,” said Freeman, board chairwoman of the growing nonprofit organization.

Before opening DASH Network, Freeman spent three years working with refugee and resettlement agencies. After graduating from TCU with a degree in advertising/public relations, she worked for the Center for Survivors of Torture in Dallas, an organization that provides mental-health and social services to refugees and asylum-seekers. She then worked for Refugee Services of Texas in Fort Worth.

Freeman was drawn to refugee issues through her work. “When you’re a kid at TCU, you don’t think about that kind of stuff,” she said. “But these are these peoples’ real lives.”

Six weeks after their wedding in 2009, Freeman and her husband, Kurtis, welcomed two asylum-seekers — women from Rwanda facing homelessness — into their home. Over the years, the couple have hosted 18 people, most of them asylum-seekers. A spiritual epiphany led Freeman to create DASH Network in 2012 using three operating pillars: housing, food and friendship. In 2018, the organization also began to offer social services such as a caseworker and classes in English as a Second Language, job skills and trauma healing.

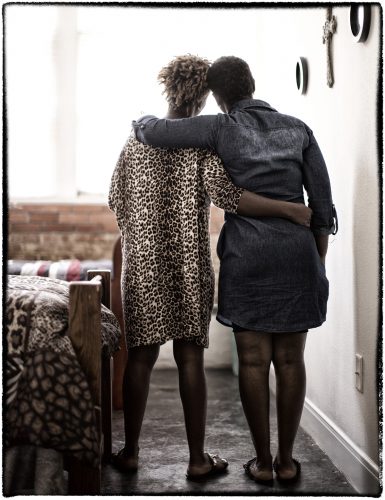

A mother and daughter seeking asylum in the United States relax after moving into an apartment DASH Network provided. Photo by Joyce Marshall

The organization’s grassroots beginnings sprang from faith. Freeman said her church “wants to be bringing God’s goodness to Earth, so there’s a big emphasis on community, on people living together,” she said. “Actually, being what the Bible calls us to do, which is love one another and [be] compassionate to others.”

Not only has faith been a catalyst and a guidance for DASH Network, it also has been a resource. Most of the nonprofit’s volunteers are from churches and faith organizations. More than 400 people have helped the nonprofit since it started, Freeman said; in 2018 there were 30 to 40 regular volunteers.

DASH Network, which has the IRS 501(c)(3) status as a nonprofit organization, gets most of its monetary donations from individuals. Businesses and groups often adopt an apartment, donating furnishings and household goods.

The Twin Sisters

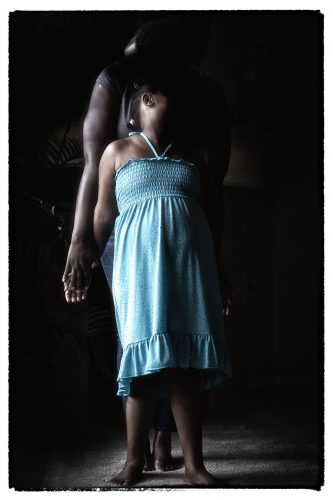

Twin sisters conceal their identities in the apartment they will live in for up to six months after they receive their work permits. Photo by Joyce Marshall

DASH Network houses men and women, but asylum-seeking women don’t live alone often. Host families are the first option to minimize risk. However, an influx of female asylum-seekers led the organization to reconsider its housing policy. The four women who arrived in July were the first ones to live in an apartment by themselves.

Host families “can be super critical for us,” said an asylum-seeker who has been able to leave the nonprofit’s housing. “As long as I am in America, I will always be involved with DASH.” He called his experience with the organization amazing.

In their new apartment, the sisters organized their new cups and utensils in kitchen cabinets. They decided on a spot for a 20-pound bag of rice, a staple food in the country from which they fled.

The twins touched American soil for the first time in April 2018. They had traveled from central Africa to Cuba, then made their way through Mexico. They endured “a lot of suffering,” said one of the sisters. It took them six months to reach Texas; they crossed into the U.S. at a legal border entry point.

Twin sisters seeking asylum in the U.S. stand in their new home provided by DASH Network, a nonprofit organization in Fort Worth that focuses on the needs of asylum-seekers. Photo by Joyce Marshall

The 27-year-old sisters were detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, per U.S. policy. They were released after passing a credible fear interview, in which an asylum officer determined they faced a credible fear of torture. They were the first asylum-seekers to come to DASH Network direct from detention, after Freeman received a call from Casa Marianella, a shelter for immigrants and asylum-seekers in Austin, Texas. Casa did not have room for the sisters, so DASH welcomed them.

The sisters will live in the apartment for up to six months after they receive their work permits. That government process, Freeman said, can take from eight months to more than four years.

“We have altogether housed and fed and befriended and given services to over 120 [asylum-seekers]. We are with [them] for the long haul,” Freeman said. “We have a 98 percent success rate of people, once they get a work permit, of being launched into financial independence.”

Mother and Daughter

By 11:30 a.m. that Saturday in July, move-in day was nearly complete. Trips up and down the elevator had stopped. Volunteers hung paintings, made beds, stocked bathrooms with toiletries. They laughed, joked and talked about their summers while putting together lamps, laying down rugs, hanging drapes and shower curtains, and moving excess items to the hall.

When the second pair of asylum-seekers — a mother and daughter — walked in, volunteers grew quiet. The mother, with her 7-year-old gripped tight at her waist, hugged the nonprofit’s staff one by one. Volunteers looked into the bedroom as the family of two sat down on their new beds.

A mother and daughter seeking asylum in the U.S. move into their new home provided by DASH Network. “I felt free in a way,” the mother said. “I have a roof over my head.”

The mother, holding on to Marilee Travitz, director of operations for DASH Network, looked up, smiled, took a deep breath. She began to cry.

“I felt free in a way,” the mother said. “I had a roof over my head.

“We all have [bad] things back home,” she added. “[It’s] knowing you have a place to rest your head.”

Mother and daughter have been in the U.S. since January 2018. They had traveled from an African country to New Jersey and finally to Texas. They were staying in Dallas when they found DASH Network in Fort Worth.

The mother said it has been difficult adjusting to life in a new country. Her daughter has had a tough time with new people, a new language and a different culture. It’s hard “to deal with that on top of what I’m dealing with emotionally,” the mother said.

In recent years, sub-Saharan Africa has been the most common region from which DASH members have fled a militant or oppressive government. In the past year, DASH Network has had residents from Congo, Uganda, Zimbabwe, Angola, South Sudan, Rwanda and Eritrea, as well as a few asylum-seekers from Kurdistan.

North Texas makes sense for many asylum-seekers from Africa and the Middle East. Some have family here, and the area is close to the U.S.-Mexico border. The Dallas-Fort Worth area is also a major international hub. And the North Texas climate is similar to that of their native countries.

By noon, most of the volunteers had left the apartment building. They will return in a few weeks when more asylum-seekers will be ready for move-in day.

DASH Network’s Travitz stayed behind to talk with the families. As director of operations, her duties include helping asylum-seekers get acclimated, organizing volunteers for moving days and working with the apartment building on lease agreements.

DASH’s asylum-seekers have a say in some of its operations. For instance, the organization changed its method of providing food to make it more efficient with input from the residents, Travitz said. And when asylum-seeking graduates leave the nonprofit’s cocoon of support, they participate in an exit interview to provide valuable feedback for the small staff.

“One thing that we consistently hear is that we gave them dignity,” Freeman said.

The Legal Process

Move-in day is just the middle of the asylum-seekers’ journeys. An American apartment is a reprieve from the constant travel and legal proceedings that have come before.

Those seeking asylum are automatically detained at the U.S.-Mexico border unless they arrive with a valid visa. To obtain asylum, they must prove they are being persecuted, using medical records, death certificates, prison records, testimonies and/or other official documents.

Most of the asylum-seekers DASH helps have entered the U.S. through the affirmative asylum process. They are generally from well-off backgrounds but have lost everything. Photo by Joyce Marshall

There are two paths to seeking asylum: affirmative and defensive. To seek asylum under the affirmative process, applicants must have a valid visa. They submit an application and then present their evidence to an asylum officer. For DASH Network’s clients, the nearest office is in Houston. In Texas, fewer than 9 percent of asylum applications are granted based on the initial interview.

Most of DASH Network’s asylum-seekers have entered the U.S. through the affirmative asylum process. They are generally from well-off backgrounds but have lost everything, Freeman said. Many can speak several languages, she noted.

Those denied asylum on the initial interview and those not eligible for the affirmative process go through the defensive process. They must appear before an immigration judge who decides if they can stay in the U.S. These court dates can take years to schedule.

The all-day appearances, held at Dallas Immigration Court, resemble criminal hearings, with the asylum-seekers’ counsel facing off against ICE lawyers. In the U.S., win rates for the defensive process hovered around 30 percent in 2012-2016.

The lengthy and tedious legal proceedings and her interactions with asylum-seekers have altered the way Freeman thinks about immigration. “I think it’s not until you meet these people that you really start to care,” Freeman said. “All the same things that we feel deep down, they feel those too. These are people.”

Putting a face on it can make you want to change your opinions, she said.

The Friendships

Friendship is another DASH Network founding pillar. The nonprofit wants asylum-seekers to not only survive, but to be happy. That’s why input from residential members is important and why they try as often as possible to meet and hang out together.

Ashley Freeman says goodbye to several-asylum seekers after an informal lunch. Photo by Joyce Marshall

Outside of monthly and occasionally weekly meetings complete with agendas and speakers, DASH Network organizes recreational activities for members, staffers and their families. Barbecues, picnics and trips to the park are social events at which asylum-seekers can build a network of friends who over time become like family.

At a meeting in late July, dusk had fallen, but the heat hadn’t abated. DASH members congregated in the computer room of the apartment building. Travitz, whose visiting parents sat in on the meeting, had set up a portable air conditioner in a corner of the room.

Asylum-seekers started to arrive. Some wore traditional African attire: bright yellows and oranges and long, flowing dresses. Others adopted a more Western style: denim jackets, yoga pants. A couple and their 13-year-old daughter sat in the circle of chairs. The parents chatted in Portuguese, while their daughter spoke near-fluent English.

The four new asylum-seekers were there, laughing, comfortable. DASH Network advocates, hosts and volunteers made sure to say hello and ask how they were doing.

Since moving into the apartment, the 7-year-old has been trying to teach the twins English. The mother laughed, saying that her daughter has been spending more time with the sisters than with her.

The meeting was run by Munatsi Manyande, newly named as the executive director of DASH Network. He walked around handing out drinks from a cooler. The 7-year-old refused water and reached for a can of Coke with a mischievous grin.

Manyande, speaking slowly and loudly in English, tackled the agenda with speed and precision. Members, volunteers, staff and advocates each contributed an anecdote about their week. Travitz passed around stipends to each member, small amounts for things other than food.

Ashley Freeman, with the help of former asylum-seeker Gustavo Domingos, left, who now volunteers and helps translate, talks about the DASH Network. Photo by Joyce Marshall

As each person spoke, the rest celebrated the speaker’s progress in learning English. All were able to say their names and where they’re from in English. Group members asked about work, family and day-to-day activities. Manyande asked if there were anything DASH Network could do better. This question is a staple at the meetings. No one had any suggestions this time.

Manyande brought out a cake to celebrate July birthdays. The asylum-seekers sang “Happy Birthday” in Portuguese, French and finally in English. The meeting’s formal proceedings at an end, people broke off into groups, eating cake and chatting.

In August, the asylum-seekers met at the pool and patio area of an apartment complex where DASH’s director of internal relations, Monica Orjuela ’15, lives. This time there was no agenda. Instead the grill sizzled with food. The late-summer aromas of meat and chlorine filled the air.

Staff members and asylum-seekers were in abundance, with children running everywhere. Manyande’s two sons wore matching Cars swimming trunks. His daughter was in the pool with the daughter of an asylum-seeker. “High-five,” she said and slapped the other girl’s hand.

Freeman and Travitz also were there with their children, who mingled and played with the other kids.

The four new asylum-seekers were stationed in a cabana on the outskirts of the pool. The mother helped her young daughter change into her bathing suit. The women chatted in French and Swahili while taking pictures and selfies.

Staff members try to put together gatherings such as this as much as they can, Manyande said. They all consider this their extended family, he added.

Ashley Freeman, founder and board chairwoman, center, and Marilee Travitz, director of operations, celebrate the appointment of Munatsi Manyande, left, as executive directive of DASH. Photo by Joyce Marshall

Freeman announced that the food was ready. She assured one of the twin sisters, a vegetarian, that there was still plenty she could eat. The sun started to descend. It was dark but still hot, a fact that generated comment from many asylum-seekers.

After the food and conversation, people started to depart. The asylum-seekers left with hugs as they returned to their new American homes.

“People ask me if I love this job,” Travitz said. “[I think] that is a funny question. I don’t love this job; I wish that DASH didn’t have to exist, that the world wasn’t so broken. [But] I love that I am able to give what I can.”

As the nonprofit’s new day-to-day leader, Manyande is focusing on local efforts to create a centralized network to unite asylum-seeker organizations around the country. He, Freeman and Travitz lamented a lack of coordinated standards.

While there are hundreds of refugee organizations in the U.S., asylum-seekers often go without meaningful assistance. “There’s only a sprinkling of seeker housing organizations throughout the country, and there’s no system; they’re not connected,” Freeman said.

“DASH has created a scenario where I can actually meet someone else’s needs. My needs are secondary in DASH,” Manyande said. “Christianity is about loving your neighbor instead of letting your neighbor love you. [DASH is] an opportunity to worry about my neighbor.”

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related reading:

Alumni, Features

Making a Difference Through Medical Nonprofits

Four alumni physicians have a heart for healing and work to make the world a better place — one patient at a time.

Features

Warrior for Peace

Nobel laureate Leymah Gbowee mobilized women to demand an end to Liberia’s second civil war.

Alumni, Features

Swanee Hunt Pushes for Inclusion of Women in Peace Building

The humanitarian champions women helping their countries recover from war.