Community Scholars Bring New Perspectives

Scholarship program opens up a world of possibilities to North Texas’s underserved elite students.

Learning to play golf doesn’t often lead to an academic scholarship, but that’s what happened for Courtland MacQueenette ’16.

One afternoon in 2003, the then-10-year-old was caddying for his father on a course in Fort Worth. Long wait times forced a merger with the group ahead. Walking between holes, MacQueenette told the new acquaintances that his collegiate dream was to attend TCU.

One member of the golfing group was Darron Turner ’87 (EdD ’11), who was then an associate vice chancellor for student affairs and in charge of a new academic scholarship program. MacQueenette remembered that Turner told him, “If you work hard, there’s this program called Community Scholars that may open its doors for you.”

At the time, the first 12 Community Scholars, who enrolled in Fall 2000 with full academic scholarships, were midway through their four years at the university. All were high-achieving students from Fort Worth-area high schools with large minority student enrollments.

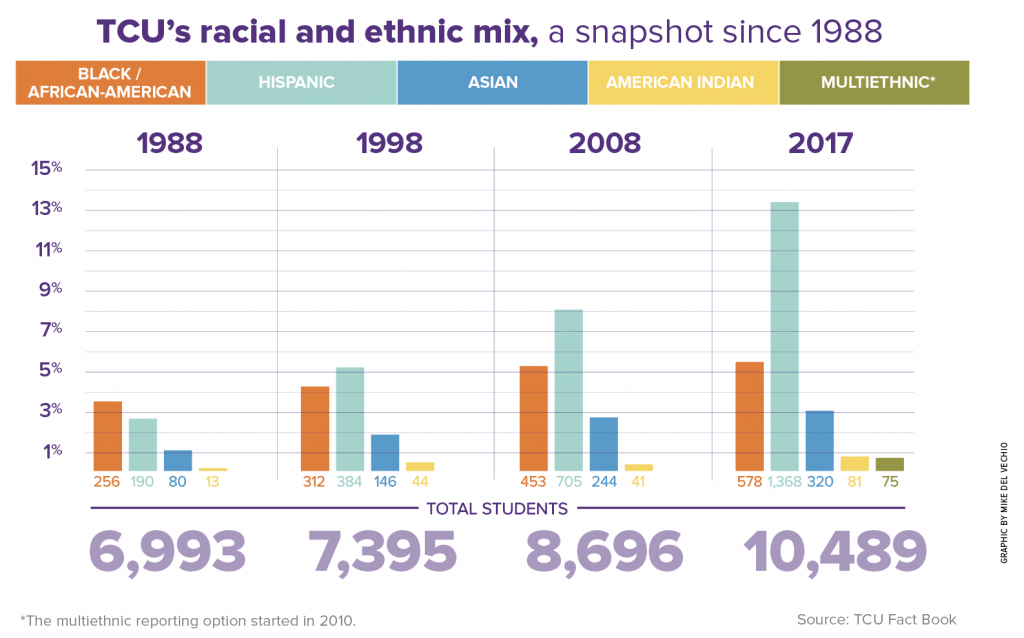

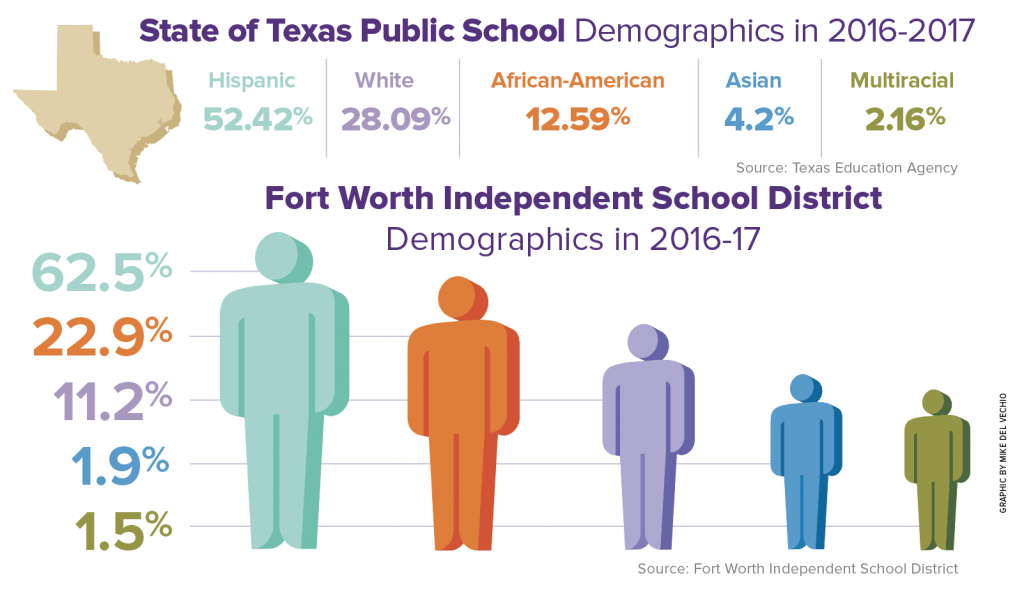

In the late 1990s, TCU made a university goal to increase the demographic diversity of its majority-white student body. To achieve that objective, the university courted the brightest students from several of Fort Worth’s minority-majority public high schools through the new scholarship program.

All of the inaugural class of scholars graduated, and 11 of them enrolled in postgraduate programs. The scholarship program’s first students transformed the university with their participation in campus life, such as establishing new student groups including the United Latino Association and the Asian and Asian-American sorority, Kappa Lambda Delta.

“Now, that door is open,” said Turner, now chief inclusion officer and Title IX coordinator, about the successes of scholars in the program’s early years. When Turner arrived at TCU in 1982 to play football, he was one of about 100 African-American male students on campus, almost all of whom were athletes.

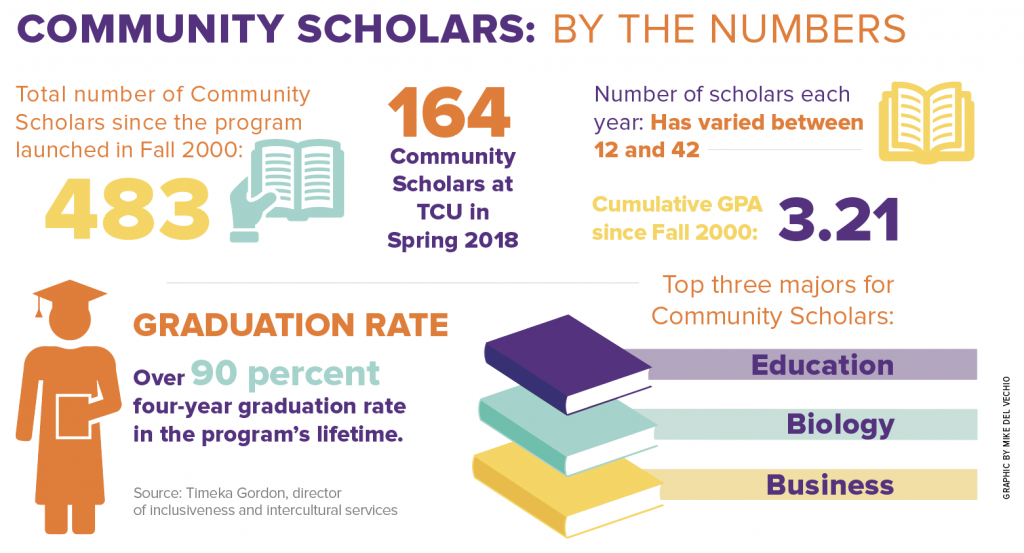

In the 2017-18 academic year, the Community Scholars Program had 164 students from 13 high schools in North Texas.

Timeka Gordon, director of inclusiveness and intercultural services and the Community Scholars Program, said she strives to keep the academic scholarship’s intent intact as the number of recipients has grown.

“Community Scholars [were] to help make TCU more diverse,” she said, “not just in terms of racial and ethnic and gender diversity, but in thought and in experiences and background.”

Thinking Local

By keeping more talent near home, TCU is providing a valuable service to the Fort Worth business community, said Robert Sturns ’97 MBA, economic development director for the city.

“As we continue to attract new companies, grow our existing companies and just grow as an overall community, there is a significant concern about having the associated workforce to take advantage of those jobs,” Sturns said. “We can’t import enough students into the area to fill those types of jobs.”

Turner said he was “extremely hard” on the first groups of Community Scholars to ensure they evolved from top-notch students into successful leaders in the workforce and community. He told the students, “You got to show the powers that be that the recruitment from the schools you come from is important and that you can succeed here.”

Lisa Cano (center) stands with her parents, Joe and Maria, in front of her alma mater, North Side High School, where she returns to talk with students about the Community Scholars Program. Photo by Leo Wesson

Lisa Cano ’05 said she felt the pressure to do well at TCU. “We took personal responsibility for the success of the program because we knew that at any point, TCU could say, nah, we really don’t need it anymore. … But if [we’re] successful, then people behind us can continue into the program because [the university] saw the value in it.”

With a degree in marketing and management, Cano works as a human resources business partner for Coca-Cola. She said her academic experience — at TCU and in the scholarship program — helps her work well with everyone she encounters.

When the inaugural scholars were freshmen at TCU, Cano was a senior at North Side High School in Fort Worth. No one in her family had gone to a four-year college, but she was ambitious, a good student and determined to pursue higher education.

At first, Cano said TCU was not a college consideration, even though she lived about 6 miles north of campus — “I never really knew it was here.” She was thinking about applying to Baylor University and praying for a hefty financial assistance package. But a high school counselor told Cano about the Community Scholars Program. She visited the TCU campus and “fell in love.”

Cano’s parents saw how excited she was about attending TCU. “I knew it was something she really wanted,” said Lisa’s mother, Maria Cano, who was born in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico.

But Cano said she didn’t realize until later how nervous her parents were about TCU — how hopeful they were about the possibility of admission but terrified that they couldn’t support her college dreams on their incomes.

When the university letter with the TCU Community Scholars Program logo arrived in her mailbox, Cano was at school. Her mother couldn’t help but read it. “I think I was more anxious than [my daughter],” Maria Cano said.

When Lisa Cano opened the car door for a ride home from school, the aspiring college student saw the TCU envelope on the passenger’s seat. “My mom was already crying,” she said. “I could tell they were happy tears.”

During Cano’s years at TCU, she invited her nephews to visit her on campus. She is six years older than one nephew, Francisco “Frank” Cano ’10, and is like a sister to him. They attended the same elementary school, he said, and “she used to walk me across the street to school.”

His aunt kept holding his hand metaphorically, nudging him along on a route to college. “She didn’t have someone to lead that path,” Frank Cano said. “That’s kind of what she did for me.”

About the scholarship program, Frank Cano said his aunt told him: “This is available to you if you work hard enough, apply yourself.” He took her advice and earned a spot in the incoming Community Scholars class in 2006.

Frank Cano, who earned a political science degree, works for a brokerage firm. He also volunteers as a financial coach with United Way. He said he wants to spread the message that success is attainable for everyone, which is something his aunt taught him. “I think once you kind of have a taste [of success], it’s something that you want to share.”

Built-in Support

Since at least 70 percent of incoming students in the Community Scholars Program are first-generation college students, their parents often have questions about campus life.

During college-introduction events for parents, they ask questions about what it means for their children to live on campus (which Community Scholars must do all four years), whether to expect them home very often (no) and if a college degree will disrupt the family hierarchy (probably not).

William MacQueenette, a battalion chief with the Fort Worth Fire Department, said he was reassured about his son Courtland MacQueenette ’16 being a Community Scholar when he learned more about the family element from program administrators. Photo by Leo Wesson

MacQueenette’s father, William, is a battalion chief with the Fort Worth Fire Department. As a parent, the elder MacQueenette said he was reassured when program administrators said that they would be there at every step to support the students. The message: The Community Scholars Program “is family.”

While parents get a crash course on college, incoming scholars attend Frog Camp to learn about university traditions and get acquainted. A week before fall classes, the students participate in Bridging the Gap, a multiday welcome-to-college intensive program where they learn more about their scholarship’s requirements.

Besides campus residency, Community Scholars must complete a series of leadership-training sessions, attend a significant number of cultural awareness events, participate in academic workshops and perform community service. They also must maintain a 2.75 GPA each semester and overall.

“This is a program,” Gordon said, “not just a scholarship.”

MacQueenette said the leadership training and cultural awareness events were invaluable lessons for his post-college life. “There’s so much you get from those extra classes, and going through them, sometimes they might seem trivial, but I feel there was never a time when I didn’t walk out of those classes with some golden nugget to help me in some way to make my character better.”

As part of the 2017 edition of Bridging the Gap, three upperclassmen scholars sat on a panel to share wisdom gained from their early college years.

Caitlin Reed, a junior studio art major, is a current Community Scholar who shares her insights about the TCU experience with freshmen scholars. Photo by Leo Wesson

Caitlin Reed, a junior, assured the freshmen that stumbling blocks wouldn’t be the end of the world. For example, she dropped a math class because of a bad grade — unthinkable to her high-achieving high school self — but picked herself up and continued with academic success as a studio art major.

Emi Gomez, a junior psychology and Spanish major, explained how a part-time job doing floral arrangements at a grocery store devoured her time. She took the job because she didn’t want to ask her parents for money for personal items, such as shampoo.

But as a result of the work hours, Gomez said, “On the weekends I didn’t have time to study, and I also didn’t have time to relax or hang out with friends.”

Julian Escamilla told the freshmen scholars about his summer study-abroad trip to China. New cultural experiences — and interacting with students from wealthier backgrounds — would be a part of the TCU experience to embrace. “You have to be aware and just open for conversations to happen, so you can learn about where this person comes from and explain to them where you come from,” said Escamilla, a senior political science major.

When the floor opened for questions, the freshmen scholars wanted the upperclassmen to elaborate on the advantages of double-majoring, or the practicality of double-majoring and double-minoring. “Just don’t pull all-nighters. It’s not worth it,” Escamilla said, before reminding the incoming scholars that the program is like a big family, and support is always available. “All you have to do is ask.”

‘Culture Shock’

In deciding to pursue a college education, Escamilla said he admired his parents and their industriousness, but he didn’t want to replicate the 16-hour days and all-night work shifts. His father is a manager at a store distribution center, and his mother works two jobs, including as a real estate agent.

While Julian Escamilla grew up in a middle-class town, he had never been exposed to the affluence of some of his classmates. Photo by Leo Wesson

“We’ve always told him that we want better for you and your brothers, and we want you to have more than what your father and I have been able to give you,” said his mother, Diana Escamilla.

Without a sizable scholarship, she said, her son’s collegiate option would have been to attend a public university where his father’s veterans benefits would have covered tuition, live at home in DeSoto, Texas, and commute to campus.

Diana Escamilla said she knew her son wanted to attend a university with small classes where professors also could become mentors, and she also knew he wanted the experience of living on campus. But without financial help, she said, “we don’t have the means.”

Julian Escamilla knew that TCU was the university for him, but, “I just remember when I got here, just being in complete culture shock,” he said. While he grew up in a middle-class town, he had never been exposed to the affluence of some of his classmates, whom he overheard discussing the costs of their private high schools and their summer vacations in Europe.

Escamilla’s freshman-year roommate was from Minnesota, and his father had been captain of the golf team at Princeton. While the two students got along, Escamilla said his roommate grew a little weary of his preferred musical genre, “grimy hip-hop.”

But Escamilla had a built-in set of classmates with backgrounds and experiences similar to his own: his fellow Community Scholars. They all went to high schools where white students were the minority. They didn’t have money for expensive spring-break trips or nights on the town, so they found more affordable ways to entertain themselves.

A robust college experience mattered, too. Escamilla was reassured about his choice of TCU while taking a course from Santiago Piñón, assistant professor of religion. “It’s nice to see that people like me can make it. … They can do better for themselves,” he said. “Representation does matter, especially in higher education.”

A law-firm internship exposed Escamilla to a copyright battle between shoe companies. That work opportunity led to tentative plans to enroll in law school and perhaps someday to specialize in intellectual property law.

“You have to be aware and just open for conversations to happen, so you can learn about where this person comes from and explain to them where you come from.”

Julian Escamilla

Without the scholarship program, Escamilla said, none of his dreams would be emerging. “I will just wake up sometimes and be like, wow, I’m really here,” he said. The Community Scholars Program “awarded me this opportunity to live a good life, to have the opportunity to set up a very successful future.”

Opportunity Within Reach

Victoria Herrera ’03 MLA, admissions director for the Community Scholars Program, grew up near North Side High School in the 1970s. “I knew about TCU, but that’s all,” she said. “I knew it was like the Emerald City.”

Nowadays, Herrera, who received her bachelor’s degree from the University of Texas at Arlington, visits North Texas high schools to recruit students for the program.

On a September 2017 stop at Diamond Hill-Jarvis High School, she delivered a pitch to about 20 senior students at the top of their class. She urged the students not to discount TCU because of its proximity to home.

She spent as much time selling the university as she did explaining the program’s admission requirements. She noted that the scholarship includes study-abroad funds because TCU wants all graduates to acquire a global perspective.

“These students have options,” Herrera said after her presentation. At the schools she visits, high-achieving students are “hungry” to learn all about higher education, perhaps because many will be the first in their families to attend college. “They want an opportunity. They want the chance. We want them to have that chance, a life-changing chance.”

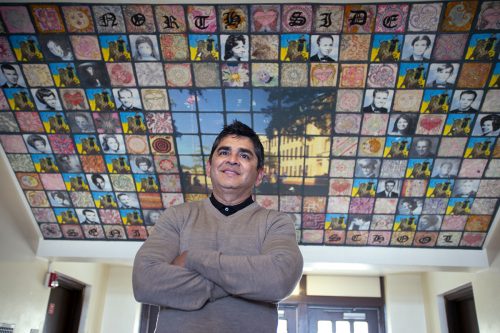

North Side High School principal Tony Martinez says that without the Community Scholars Program, his students could not afford to attend TCU. Photo by Leo Wesson

North Side High School principal Antonio “Tony” Martinez ’83 said the scholarship program is crucial to solidifying the link between TCU and his school. “None of my kids would ever be able to experience a school like TCU due to the tuition cost.

“It’s fantastic to see some of my students be able to experience an education from TCU,” Martinez said. “I received a fantastic one, so I’m glad that they’re there.”

Students at Fort Worth-area public high schools with large minority populations now see TCU as a viable option. Herrera estimated that overall admission applications from the 13 eligible high schools increased by almost 25 percent in the past three years. Part of the increase is related to applicants vying for a spot. Another part, Herrera believes, is word of mouth.

While academic scholarships exist beyond the Community Scholars Program, reality hits when Herrera tells high school students about the cost of attending TCU. “They just all gasp,” she said.

But then, most high school students worry about the cost of college. “When we do our senior exit survey … the key thing we find across the board is that they’re concerned about, financially, how am I going to do it,” said Anita Perry, director of academic advisement for the Fort Worth Independent School District. “The aspiration is there to want to further their education. However, [the question is] … ‘How am I going to pay for it?’ ”

The Community Scholars Program is “providing students the opportunity to continue their education” without that worry, Perry said. As a result, TCU is no longer “something that’s unattainable, unreachable.”

Life-changing Choices

In 2017, about 300 Community Scholar applicants went through the standard admissions process and submitted an extra essay for scholarship consideration.

Herrera worked with Gordon to cull those applicants to 88 finalists. Then they invited the prospective recipients and their families to campus for a formal dinner. In addition, TCU offered live translation services to parents who didn’t speak English. (Translators spoke in Spanish, Vietnamese and Swahili.)

“Their families, a lot of them — the majority of them — have never been on a college campus before. They’re nervous,” Herrera said. “They’re praying.”

Diana Escamilla was once one of those parents. “We were just in awe,” she said about the dinner for the scholarship finalists. But the life-changing implications of the evening were hard to ignore. “You look around the room and it tugs a little at your heart.”

Each of the 88 finalists returned to campus the next day for interviews with panels of faculty, staff, alumni and volunteers. And then another interview with Gordon. The seven-minute sessions were the prospective recipients’ final opportunity to distinguish themselves.

Patrice Spears ’16 was a Community Scholar at TCU and now helps students at Dunbar High School gain the same opportunity. Photo by Leo Wesson

When Patrice Spears ’16 interviewed with Gordon, she told the program administrator how her mother gave up a career to care for her only child, who had open-heart surgery at 3. “If I’m going to do this,” Spears recalled saying during her interview, “it’s not only going to be for me — it’s going to be for my mom, too.”

Each year after the interviews, Herrera and Gordon make the selections for about 40 spots. “It’s like a war room,” Gordon said.

“We go back and forth,” Herrera said. “We compromise. We argue. We hug. We cry.”

But they must decide. How? “We value more than just a test score and a class rank,” Gordon said. “Can the student make an impact at TCU?” For example, might a prospective recipient follow in the footsteps of Courtland MacQueenette and Julian Escamilla? Both served as fraternity presidents of Alpha Phi Alpha and led the group’s Day of Service on campus.

William MacQueenette said he knew that for his son, TCU would be an “opportunity to open your horizons, see different things, do different things, get away from the normal, if you would, of what traditionally maybe an African-American would be around.”

Gordon said she understands that 40 young lives — and 40 families — change with the decision to offer the academic scholarship. To honor the magnitude of the award, Gordon decided a few years ago to make surprise visits to high schools, complete with cake and balloons.

On a school day in March 2012, Gordon showed up at DeSoto High School to congratulate Spears and several of her classmates.

“I can remember that day like it was yesterday,” Spears said.

When Gordon announced that the assembled students were Community Scholars, should they accept the challenge, “I fell out,” Spears said. Then she called her mother: “I had to move the phone because she’s screaming so loud in my ear. She’s like, ‘No way! No way!’ ”

Spears earned a journalism degree but decided to focus her career on helping other students achieve dreams beyond their expectations. Today, she is a TCU College Advising Corps member stationed at Dunbar High School in southeast Fort Worth. Many Dunbar students see athletics as the only ticket to college, and Spears explains other options.

“If you’re not one of those kids that is lucky enough to get a scholarship offer for basketball or track or football, there’s another avenue for you,” Spears said. “You can still be yourself. You can be that brainy, smart kid and get college paid for, just like the best athlete.”

A Bigger Story

During that golf-course walk in 2003, Courtland MacQueenette listened to Turner and later followed his advice. At Dunbar High School, he played football, ran track, and joined the robotics club and the drama team.

In 2009, his mother, Michelle, died. He was a high school sophomore. Before her death, MacQueenette promised that he would become class valedictorian and earn a college degree.

Courtland MacQueenette ’16, a former Community Scholar, returns to campus during a visit to Fort Worth to reconnect with family and friends. Photo by Leo Wesson

Stellar grades landed MacQueenette at the top of his senior class at Dunbar and led to offers from Harvard, Dartmouth and Texas A&M. He was on the path to become the first person in his family to earn a degree from a four-year college.

Just as MacQueenette had announced as a 10-year-old, TCU was his first choice. But without financial assistance in the form of an academic scholarship, he said he wouldn’t ask his widowed father to foot the bill.

The spring of his senior year, MacQueenette watched television news reports about local high school students receiving community scholarship offers. On the day the program administrators came to Dunbar, MacQueenette — the lone recipient in his graduating class — was out of town touring Texas A&M.

A few nights later, MacQueenette heard a knock at his front door. Michael Marshall ’07 MLA (EdD ’16), admissions director for the Community Scholars Program in 2012, was on the doorstep. Marshall was carrying a TCU letter with an offer of a full academic scholarship.

MacQueenette exhaled and said a calm thank you to Marshall. “I let him out and closed the door and ran around the house screaming, yelling.”

Then MacQueenette called his father, who was out bowling. Then William MacQueenette called everyone in the family. Within 30 minutes, the entire crew was at the house to celebrate.

MacQueenette said his family’s presence made him realize “how impactful that the scholarship can be, and how it doesn’t affect just the child that’s receiving it. It really affects their family.”

William MacQueenette said that his son’s academic scholarship “helped us, knowing that there are opportunities for all who want to dedicate themselves, put forth the effort to be better, to go farther and to progress in a positive manner in life.”

Community Scholars have maintained better than a 90 percent four-year graduation rate for the lifetime of the program.

“They’ve excelled here,” Darron Turner said. “They help Fort Worth be a better place. And they help TCU be a better place.”

For people living in the north-side neighborhood of Herrera’s youth, she said TCU is no longer the Emerald City. Whenever she returns to visit friends or dine at a taqueria, “you’ll see somebody walking with a TCU T-shirt … and you think, wow, things have changed.”

North Side High principal Martinez agreed: “It’s amazing how many of our students have TCU stuff on.”

The same sentiment goes for southeast Fort Worth around Dunbar High School. Courtland MacQueenette said he was proud to represent his high school’s neighborhood, Stop Six, to his college classmates. “A lot of students … stay in the TCU bubble,” he said. “It’s not OK to do that.

“You’re much better for going out there and experiencing these things yourself and questioning the whys — why is this the normative thing we think of Berry Street or Stop Six?”

“They’ve excelled here. They help Fort Worth be a better place. And they help TCU be a better place.”

Darron Turner

MacQueenette earned an engineering degree, fulfilling the promise to his mother. Today, he works in leadership development at Textron. He uses those extra lessons in cultural awareness and practical leadership that he learned as a Community Scholar to bolster his soft skills in a field where workers often lack them.

MacQueenette said he has a much wider perspective on the world and what he can do to improve it. And the fact that he and the rest of the Community Scholars are part of the TCU community benefits everyone. The more inclusive and diverse the people at the university, “the more chance we have for students to step outside of their own personal bubbles and really learn to be global citizens.”

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related reading:

Letters

Community Scholars Represent the Promise of Broader Goals

From Chancellor Boschini: TCU has undergone a significant campus transformation in recent years that extends beyond new facilities.

Features

Michael Ferrari’s Vision for Diversity

The former chancellor’s plans to shift demographics inspired an academic scholarship.

Alumni, Campus News: Alma Matters, Web Extras

Q&A with Darron Turner, TCU’s first chief inclusion officer

As chief inclusion officer, Darron Turner will collaborate with faculty, staff and students to ensure everyone’s voice is valued.