Photo collage by Kim Baker

An Epic Comeback

Three decades ago, dedicated alumni led a drive to rebuild TCU’s left-behind athletics program.

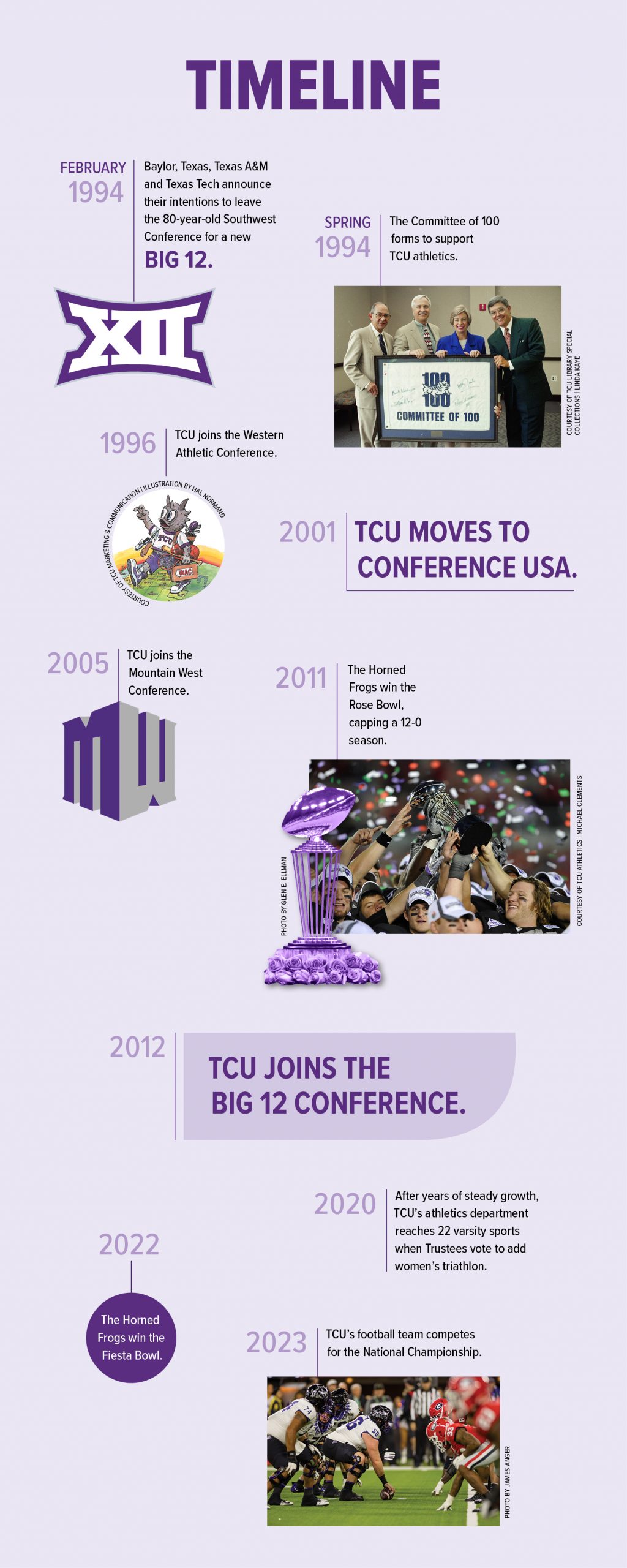

Not long after Valentine’s Day 1994, Baylor, Texas A&M, the University of Texas and Texas Tech announced they were dumping the Southwest Conference for the Big Eight, turning it into the Big 12. The Horned Frogs weren’t invited to the party.

Heartache ensued. TCU had been playing in the league for more than 70 years, since joining the Southwest Conference in 1923. The football team won national championships in 1935 and 1938. In the 1950s, the Horned Frogs ranked among the best gridiron squads in the nation. The decades-long fall from such great heights landed with an agonizing thud.

Following the crushing announcement, the university could have wallowed in self-pity or grievance or even abandoned Division I competition altogether. Though difficult to imagine now, shuttering Horned Frog varsity sports was discussed in those dark breakup days.

Instead, dedicated alumni and Trustees led by John V. Roach ’61 (MBA ’65) and Dee Kelly ’50 came together to rally the wider TCU community in a moment when most on-campus sports facilities desperately needed updating, and fan support — as well as institutional funding — had dwindled. When TCU joined the Western Athletic Conference after the Southwest Conference’s official demise in 1996, those alumni aimed to make the arrangement a temporary stop.

The passion they put behind the game-changing effort helped put TCU on its upward trajectory.

“TCU had a long tradition of competitive athletics,” said Emeritus Trustee Luther King ’62 (MBA ’66), whose ongoing tenure on the Board of Trustees included a stint as chair. “At the time the Southwest Conference unwound, a group of alumni and donors made the decision to play as high a level of football and competitive athletics for as long as we could.”

“We needed to get more people in seats. That was the first step in positioning TCU to compete against the best schools in the country.”

Trustee Amy Roach Bailey ’89

He and others recognized that any road to restoring the university’s athletic success had to be paved with more than mere intentions. Amy Roach Bailey ’89 said her father, the late John Roach, believed that filling the stadium’s seats at football games could help turn the tide in TCU’s favor.

Prior to the 1994 football season, Bailey said, “he started a grassroots effort with everyone rolling up their sleeves.”

His goal: rally support for TCU athletics and fill the stands, once again, with purple.

Roach’s Hail Mary took the form of the Committee of 100, which the legendary CEO of RadioShack founded. This fertile collaboration of alumni, community members and TCU stakeholders helped raise money, attract new fans and build a foundation for the current golden age of athletics.

Ultimately, Bailey said, there was a silver lining to the breakup of the Southwest Conference. “TCU took this situation and spurred a positive initiative that reaped overwhelming benefits for the university.”

“There were a lot of mountains to climb,” said former head football coach Gary Patterson. “It does take a village to make the moves that we made.”

Long-Term Vision

The flagging fortunes of TCU Football left the entire athletic program vulnerable after the upheaval in the Southwest Conference. In early 1994, the university’s highest-profile team had enjoyed only two winning seasons since 1965 (1984 and 1991, for anyone keeping score).

Bailey, a TCU Trustee, experienced nothing but losing seasons during her student years, from 1985 to 1989. Worse, she said, “throughout my lifetime the majority of Amon G. Carter had been filled with opposing fans.”

Five years after she finished her degree, Frogs near and far reeled at news of the chaos on the conference landscape.

“I was sitting in the chancellor’s office, getting ready for a Cabinet meeting, when we found out the four teams were leaving the Southwest Conference,” said Don Mills ’72 MDiv, former vice chancellor of student affairs who worked at TCU for more than a half-century. “Everyone knew that Texas was unhappy, but we didn’t know four schools would bolt.”

The next TCU Daily Skiff issue featured headlines indicative of the fretful mood across campus: “Officials scramble to answer questions” and “Big 8 deal may affect admissions.”

“We were left for dead on the side of the road,” said Lois Kolkhorst ’88, a TCU golf letter winner who worked in sports information and marketing for the university early in her career. She went on to serve seven terms in the Texas House before becoming the state’s 17th female state senator in 2014, an elected position she still holds today.

In May 1994, Bailey’s father, while chairing the Board of Trustees, came up with a plan to bolster attendance at home football games. He saw this as the first necessary step to solidifying the future of the entire university.

“John Roach had the vision that athletics could carry us further and quicker,” said Chancellor Victor J. Boschini, Jr. “For some people that was controversial. They wondered why we would spend money on that, but he was very insistent, and it turns out he was right.”

TCU’s leadership continues to embrace Roach’s vision for a thriving university, one that supports athletics through institutional investment. Boschini said he believes the university’s culture of big-time athletics not only draws students to campus but also enriches their experience once they’re here.

“Studies show that kids want to go to a university with a big sports program even if they are not athletes themselves,” Boschini said. “There’s an excitement that an athletic atmosphere brings, a zeitgeist.

“You can feel it when our teams are successful on every corner of campus.”

Painting It Purple

Back in the mid-’90s, such euphoria ringing across campus likely felt out of reach.

“We needed to get more people in seats,” Bailey said. “That was the first step in positioning TCU to compete against the best schools in the country.”

“No one wants a team in their conference that’s only getting 20,000 people in the stands, and TCU wasn’t even doing that,” Kolkhorst said. “John Roach saw that we’d gotten left behind and said we had to turn things around immediately.”

But TCU’s size created a challenge. Among schools in the four most powerful conferences in 2024, it has the second smallest undergraduate enrollment at 10,900 students. (Wake Forest remains considerably smaller at 5,500 undergraduates.)

Given the relatively small number of students and alumni, TCU’s leadership realized the school needed to rebrand as Fort Worth’s hometown team. The city’s population hovered just over 450,000 in 1994, and TCU needed widespread support from the people of Cowtown. (Today, Fort Worth is the 12th-largest U.S. city at more than 975,000 residents. It is also America’s biggest city without its own professional franchise in any major sport.)

“My husband’s philosophy was that if you lived in Fort Worth and did not go to TCU and your school was not playing against TCU, you should adopt TCU as your home team,” Jean Wiggin Roach ’66 said. “We’re not going to hold it against you if you’re an Alabama grad and we’re playing Alabama, but if you’re just free-floating, you’re up for grabs.

“It opened up another avenue of thinking about the relationship between TCU and the community,” she said.

The Committee of 100, which included Fort Worth CEOs and representatives from the Chamber of Commerce plus Horned Frog loyalists and letter winners, met on campus or at the Roach family home. Without smartphones or email, members including Bailey “handwrote notes to everyone I knew, asking them to purchase TCU football season tickets. Everyone got a note — Longhorns, Bears and Aggies included.

“Dad and Dee Kelly said to every businessman in town, ‘You’re buying tickets. It’s going to be Bell Helicopter’s Day or Tandy’s Day or whoever’s day at the stadium.’ It was all about taking where we thought we were at our worst point and deciding we were going to get through this together.”

“We’re not in Knoxville, Tennessee, or Oxford, Mississippi,” Kolkhorst said. “We knew we had to fill the stands by competing for those entertainment dollars, which meant creating a whole new atmosphere at TCU.”

Several enduring traditions grew out of the high-stakes labor of love. To foster a family atmosphere and increase attendance, the committee arranged for fireworks at football games. Kolkhorst fielded more than a few postgame calls from concerned neighbors.

Other innovations included Frog Alley, which debuted at the first home game of the 1994 season against Kansas. Kolkhorst hired face painters and a band and, mindful of the shoestring budget, recruited her immediate family as free labor to set up 200 tables. Chancellor William Tucker saw them working and stopped to help.

Around that time, the Frog Horn was unveiled at a pep rally in downtown Fort Worth.

Frog Alley was among the Committee of 100’s innovations to build fan support. The family-friendly event in front of Amon G. Carter Stadium on home game

days culminates with the TCU Marching Band and Showgirls leading fans into the stadium. Photo by James Anger

Created for the university by the Burlington Northern Railroad, the Frog Horn immediately captured hearts and made waves. The Dallas Morning News described the 3,000-pound mobile mascot as “college football’s ultimate troll.” Then as now, the horn rattles stadium seats — and teeth — at 120 decibels per blast.

“The Frog Horn is a cruel joke,” the newspaper opined. “It screams to TCU’s opponents, ‘Hey, not only are you going to lose, but you’ll be deaf by the time we’ve run up the score enough to sub in our third-stringers.’ ”

Loyal Leaders

In 1994, Roach recruited a Horned Frog baseball legend to help make the Committee of 100 a success. Roger Williams ’72, who these days represents the 25th District of Texas in Congress, vice chaired the group before assuming its leadership, at Roach’s request, in 1996. Committee members frequented Rotary Clubs, Lions Clubs and other Fort Worth gatherings to spread the word and build excitement. They visited area high schools and businesses, evangelizing for the Horned Frogs.

“TCU hit upon its niche: It’s the school of Fort Worth,” said Williams, a former TCU baseball star who went on to play in the Atlanta Braves organization. Following a career-ending injury, he returned to campus to coach the baseball team in 1976 and currently serves on the Board of Trustees.

Williams’ Horned Frog bona fides run deep, particularly concerning athletics. His car-dealer father began supplying TCU’s coaching staff with automobiles back in the 1950s. The congressman, who eventually took over and expanded the family business, proved an ideal choice to sell the Horned Frogs to Fort Worth.

In fact, Williams was so successful in his work with the Committee of 100 that he was tapped to help save his beloved baseball program. Despite a consistent record of wins, TCU Baseball found itself on the chopping block in the late ’90s. Knowing the fate of the whole program hung in the balance, the congressman led efforts to raise nearly $8 million in private funds.

Onlookers cover their ears in preparation for the unveiling of the Frog Horn, which made its debut in 1994. Courtesy of TCU Library Special Collections | Linda Kaye

“The old stadium was really lacking,” he said. “We raised the money quickly, built Lupton Stadium and then hired a great coach.” The stadium opened in 2003, the same year Jim Schlossnagle, who coached the Horned Frogs for 18 seasons, was hired to lead the team.

Meanwhile, another baseball lover was making an indelible mark on TCU. Frank Windegger ’57, who played football and baseball as an undergraduate, had returned to the university to coach baseball before taking over as athletic director in 1975. Windegger, who died in March 2024, held the position for an unprecedented 23 years. His most difficult stretch required him to steer the boat through the choppy early days of conference realignment, when the ship had a real chance of sinking.

“Frank would do almost anything for TCU except cheat,” said William Koehler, who retired in 2004 as the university’s longtime provost and vice chancellor for academic affairs. “He had a national reputation within the NCAA and coaching and AD circles.”

Koehler pointed to Windegger’s hiring of a new, high-energy men’s basketball coach in April 1994 — weeks after news broke of the four teams bolting the Southwest Conference — as providing a much-needed boost to morale in a time of athletic turmoil. Four years later, Billy Tubbs led the Horned Frogs to a perfect 14-0 regular season Western Athletic Conference record. The team scored a coveted NCAA Tournament invite as a fifth seed.

“From the inside looking out, bringing on Billy Tubbs was a tipping point,” Koehler said. “Billy was a showman and was great on interviews. We started filling Daniel-Meyer.” (Following its renovation in 2015, the 6,800-seat basketball arena was renamed for Ed and Rae Schollmaier.)

Former senior associate athletics director Jack Hesselbrock ’82 (MBA ’86) said Tubbs, with his big personality and pulse-pounding style of play, brought positive national recognition to the university at a moment that felt fraught.

“The timing was good,” Hesselbrock said. “It was right about when influential alumni came together and decided that we were going to do athletics right at TCU.”

The Committee of 100 was “instrumental in making sure that the administration was aware that if we were going to play, we wanted to be successful, and to be successful we were going to have to pay for successful people,” Mills said. “Billy Tubbs was the first big-time coach that we brought in, and that was also a signal that TCU was ready to play.”

Another pivotal hire was Eric Hyman, who succeeded Windegger as athletic director in 1998.

“I always say to the athletic director that the biggest part of the job is balancing egos, starting with your own,” Boschini said. “We have all got to be big enough to have a vision but small enough to get out of the way and let other people succeed.”

Hyman’s first mission was to find TCU’s next head football coach. He lured Dennis Franchione away from the University of New Mexico. Franchione brought a young defensive coordinator named Gary Patterson with him to Fort Worth.

Another of the new athletic director’s early tasks was implementing Operation Leap Frog, which he describes as a strategy that reflected the university’s commitment to athletics. TCU’s Trustees, in November 1998, agreed to invest $8 million with the goal of turning TCU into a school with an athletics program recognized nationwide.

“The strategy, ultimately, was to get back into a conference that was comparable to the Southwest Conference,” Hyman said. “The most realistic comment I heard from anyone at the time came from Luther King, who said that this was a wake-up call.

“He said we needed to take a step backward and build ourselves up again.”

The Ascent Begins

The football team was coming off a humiliating 1-10 season in 1997. Franchione’s first year on the job, the Horned Frogs finished with a 6-5 record and a real shot at postseason play.

“One of the reasons we hired Coach Fran was that he was a sitting head coach and had a history of recruiting from West Texas, which in the ’90s was fertile ground for really good football players,” King said. He recalled that Hyman and others traveled in fall 1998 to El Paso to lobby hard for an invitation to the 65th annual Sun Bowl.

The Committee of 100’s success at putting people in the stands — including 38,256 for the home opener on Sept. 12, 1998, against Oklahoma — was pivotal to Franchione’s pitch. Frog fans, he vowed, would paint El Paso purple if given the chance.

“I probably made 100 calls to the Sun Bowl to try and get them to take us, too,” Franchione said. The efforts paid off. On the sunny afternoon of Dec. 31, 1998, TCU met the University of Southern California in Sun Bowl Stadium.

TCU, led by quarterback and two-sport athlete Patrick Batteaux ’00, entered the 1998 Sun Bowl as 16-point underdogs. The Frogs’ 28-19 victory over USC ended a 41-year drought of bowl wins. Courtesy of TCU Athletics

TCU dominated the action, forcing the Trojans into a Sun Bowl record of fewest net yards rushing, a dubious minus 23. The Frogs won by a final score of 28-19, ending a 41-year bowl-win drought.

“Fan support makes a huge difference,” Franchione said. “I remember looking around the stadium, and I swear there were 35,000 fans wearing purple. TCU fans showed up just like I promised the bowl officials they would.”

“There were grown men coming up to us afterward crying,” said Landry Burdine ’99, a walk-on-turned-team captain who’s now the color analyst for the Horned Frog Sports Network. “It looked like a sea of purple in the stands.”

Back home, the big win invigorated the atmosphere in the athletics department.

“Beating a marquee team like USC the way we were able to,” Franchione said, “immediately changed the outside world’s perspective on TCU.”

As King put it, “The victory over USC created legitimacy to what we were trying to do.”

Future NFL Hall of Famer LaDainian Tomlinson ’05 was among the squad of running backs on that team. The next season, he kept TCU Football in the national spotlight when he rushed for a then-NCAA record 406 yards against the University of Texas at El Paso. The following year, Tomlinson won the Doak Walker Award and was a finalist for the Heisman Trophy.

Trustee Rick Wittenbraker ’70, who played on the Southwest Conference Championship-winning basketball team in 1968, believes those big national moments shape the perception and profile of a university.

“It’s one thing to pay a branding firm to blow your own horn,” Wittenbraker said. “When you go to a bowl game, the college playoffs, the College World Series or the NCAA Tournament, you have ESPN or Fox Sports or some other third party giving you an endorsement that is much more powerful.”

His former teammate James Cash ’69 understands the economics of athletics both as a former Harvard Business School professor and co-owner of the 2024 NBA champion Boston Celtics. (“It’s a very small piece,” he said with a laugh.) The former TCU Trustee, who was also the first Black athlete to play for the university, values athletics “for the human stories that people can find inspirational.”

He said he appreciates TCU’s long-term support of high-level competition. “Like my mother used to say, if you are going to do something, you should do it the right way. TCU does it the right way.”

Making Moves

When Franchione took the head coaching job at the University of Alabama, Hyman promoted Patterson to lead TCU football in December 2000.

“Gary Patterson is the key to all of this,” King said. “You’re really nothing without winning all those bowl games.” Patterson went on to become the winningest coach in program history, collecting six conference championships and an enviable 11 victories in bowl games.

Behind the scenes, Hyman capitalized on the success of Patterson’s Horned Frogs. In 2001, after a few successful years in the WAC, Hyman inked a deal for TCU to jump to Conference USA with teams that included Army, Cincinnati, Houston and Louisville. Based on the competitive nature of the conference, Hyman viewed the move as an opportunity for the university to wend its way back up the college athletics ranks, perhaps eventually to one of the nation’s top conferences.

Soon after the announcement, however, the athletic director encountered a less-than-enthusiastic response during a Frog Club golf outing. After he announced what he viewed as the outstanding news of joining Conference USA, the group of alumni let Hyman know they considered the move a comedown from the once lofty heights of the Southwest Conference.

“I was so excited, so pumped that we got into Conference USA, but, frankly, people didn’t understand it or what the significance was,” Hyman said. He “just about cried” after their collective reaction that day, he said. “Now, though, people recognize that we had to take that immediate step to get where we wanted to go.”

Hyman kept touting the increased national exposure of Conference USA. The participants resided in larger media markets, which “will give us tremendous influence on a different part of the country than we’ve had in the past — Chicago, New York City, Cincinnati, New Orleans, Louisville and Charlotte,” he said not long after the announcement.

The new conference made for a successful home. Patterson’s Frogs scored back-to-back winning seasons in 2002 and 2003, including a 2002 Liberty Bowl victory against Colorado State.

The football team’s strength paved the way for a jump to the Mountain West Conference, announced in early 2004.

The Horned Frogs flourished in the Mountain West, winning three conference championships in football. Photo by Glen E. Ellman

The league, which included BYU, Wyoming, Colorado State, Air Force, New Mexico, San Diego State, Utah and UNLV, was considered a step up. Since 1999, three-quarters of the Mountain West Conference teams had appeared in bowl games. During that time, six different men’s basketball teams appeared in the NCAA tournament.

The Mountain West had signed a seven-year, $48 million contract with ESPN for football and men’s basketball shortly after its founding in 1999. Adding a Fort Worth school, then in the nation’s seventh-largest media market, was a key reason the league wanted TCU to join its ranks.

A few months later, the Mountain West inked a bigger seven-year deal, this time with the upstart College Sports Television network. “While the conference will have to divide the financial pie nine ways now, instead of eight, the league wouldn’t have received the $82 million [TV] contract without TCU,” Deseret News, based in Salt Lake City, reported in July 2005, the month the Horned Frogs officially joined the conference.

The story quoted Danny Morrison, Hyman’s handpicked successor as athletic director, as saying, “The Mountain West is a great place for TCU. It’s a great fit academically and athletically.”

Cowtown Camden

When he was interviewing for the job, Morrison walked around the campus, taking in “its charm and first-class facilities” — everything from the Bayard H. Friedman Tennis Center to the athletics staff offices at the John Justin Athletic Center.

Success in college athletics “takes resources and donors who are highly committed and are willing to invest in facilities, infrastructure, programs and people,” Morrison said. “It also takes a very healthy university that’s moving forward on all fronts so that every part of the school is doing well.”

Morrison points to everything from faculty achievements and more competitive admissions to widespread campus improvements as measurable proof that TCU’s trajectory was on the rise in the early aughts.

“The athletic program has been a visible sign of all the progress in every part of the university [including] its increasing national presence and prestige,” Morrison said.

Consider the endowment another indication of TCU’s growth. Per Jason Safran ’01, the university’s chief investment officer, at the end of the 1995 fiscal year, the university’s endowment totaled $420.6 million. The endowment hovered around $2.7 billion at the end of the first quarter of 2024.

Back in the mid-2000s, Morrison rallied alumni including Wittenbraker, Malcolm Louden ’67, Hunter Enis ’59 (MA ’63) and Dick Lowe ’51 to support the building of an 80,000-square-foot indoor football practice facility. Named in honor of the legendary Sam Baugh ’37, the facility opened in 2007.

But Morrison had even grander dreams for TCU.

“We wanted the [football] stadium to be the Camden Yards of college football,” Morrison said. The home of the Baltimore Orioles earned raves for its family-friendly retro appeal when it opened at the start of the 1992 season. Morrison believed that vibe would translate well to Fort Worth.

Though planning for the $164 million renovation began during Morrison’s tenure — he left TCU to become the president of the Carolina Panthers in September 2009 — construction didn’t begin at Amon G. Carter Stadium until 2010. At that point, Morrison’s successor was still new to the job.

Chris Del Conte led TCU’s athletics department during the season that changed everything.

Coming Up Roses

“Chancellor Boschini and the Board of Trustees had a bold vision for the university,” said Del Conte, TCU’s athletic director from 2009 to 2017, who noted that the vision didn’t include just athletics, but the entire university. During Del Conte’s tenure, academic spending at TCU went from $189 million to $300 million.

Not that Del Conte discounts what big-time athletics have meant to Texas Christian University.

“I don’t think any university in America has benefited as much from athletics as TCU in football and Duke with men’s basketball,” he said.

“I challenge you to find another athletic program at a university our size that has consistently been committed to competing — and winning — at the highest levels of NCAA Division I sports,” said President Daniel Pullin, who describes TCU as providing the best undergraduate experience of any college or university in the country.

Then and now, football offers unrivaled opportunities to introduce audiences around the nation to a private university in Fort Worth.

TCU hosted its first ESPN College GameDay show on Nov. 14, 2009, yet another indication that the athletic program had gained traction and was generating buzz nationwide. GameDay, which debuted on the sports network in 1987, quickly became college football’s most-watched pregame show. ESPN broadcasts from a different university each week. At that point in the season, the Horned Frogs were ranked No. 4 in the nation.

The brand-new Campus Commons made its stunning debut on the national stage when the party started that November morning. Thousands of students, alumni and supporters flooded the area. That night, TCU dominated 16th-ranked Utah with a final score of 55-28.

In November 2009, ESPN’s College GameDay, co-hosted by Kirk Herbstreit, right, and Lee Corso, made its first visit to TCU. Corso donned a SuperFrog head to predict a TCU victory; the Frogs beat Utah 55-28. Photo by Glen E. Ellman

“When you have 10,000 people in the middle of campus, it makes an impression,” Patterson said. “I’ve always told people that athletics is the front porch of the house. You’re not the most important part of the house, but you’re the most visible. You get people to knock on the door because of what the outside looks like.”

Things looked up from there. The Rose Bowl victory on New Year’s Day 2011 was the crowning moment of a long road back to legitimacy for the Horned Frogs. Led by flame-haired quarterback Andy Dalton ’10, TCU capped off a perfect 12-0 season with a 21-19 nail-biting victory over Wisconsin.

“We were no longer a Bible college over in Texas. We were a national university on the back of athletics,” King said. “Thank you, Gary Patterson.”

“If people doubt the power of sports, I’d say come and sit in my office the week after winning the Rose Bowl,” Boschini said. “You could feel it on every part of the campus. My phone was ringing off the hook.”

Ten months later, the Big 12 invited TCU to join its ranks, effective July 2012.

“We were banished to the wilderness no more,” Burdine said.

“We are very appreciative of the Committee of 100 in laying the foundation for our future success,” said Jeremiah Donati, who succeeded Del Conte as TCU’s director of intercollegiate athletics in 2017. “At a critical time athletically and emotionally for us, it showed the commitment TCU had in positioning us for a positive future.”

An October 2011 announcement from the Big 12 heralding the move noted that TCU was the only school in the country to finish in the Top 10 the previous three football seasons. The news release also highlighted many of the school’s other athletic achievements, including 13 postseason men’s basketball appearances, seven of which were to the NCAA Tournament.

Other feats included 11 conference championships for the baseball team, with the first appearance in the College World Series in 2010. Men’s golf had advanced to the NCAA competition a staggering 22 years in a row, while the women’s golf team had made 16 consecutive NCAA appearances at that point. In 2010, women’s rifle had also won the NCAA championship.

TCU athletics had arrived. Again.

“Remarkable to me is not only our current athletic success, but the foresight and strategic vision of our leaders to invest in athletics,” Pullin said. “Over the last several decades, through both outstanding victories and moments of uncertainty, TCU leadership has maintained a strong commitment to athletic excellence — and it has paid off.”

Accolades, achievements and wins across TCU’s 22 varsity sports continue rolling in today. Recent highlights include the Sonny Dykes-led Frogs nabbing the 2022 Fiesta Bowl trophy and subsequent appearance in the College Football Playoff National Championship Game. TCU’s rifle team won its fourth national championship in March. Two months later, TCU men’s tennis, which won back-to-back national team indoor championships in 2022 and 2023, clinched its first NCAA championship. Under Donati’s leadership, the Frogs have won eight team national championships and 11 Big 12 Conference titles.

We have tremendous momentum in our athletics program,” said Donati, who explained that continued support of athletics is a cornerstone of the future the university intends to build from here.

“If you look at what TCU athletics has done over the years, with all of the support from donors and the community, you realize this is a story of continuous improvement,” Morrison said. “TCU doesn’t settle, nor do they get complacent.”

For those who remember the difficult times firsthand, the Horned Frogs’ success feels even sweeter.

“What started as a ground-up effort changed TCU forever,” Bailey said.

Williams, a key architect, concurred: “TCU would be a totally different school without athletics.”

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related reading:

Features

Building a Brand

Sportscaster Newy Scruggs mixes charisma with business acumen in a thriving on-camera career.

From the Chancellor

Fall is my favorite time of year because we welcome the newest class of Horned Frogs into our community.

Sports: Riff Ram

Running It Back

Buoyed by experiences on and off the field, Savion Williams prepares for his final season at TCU.