In Early Modern Spain, Food Had Social Implications

Professor Jodi Campbell dishes on the meaning behind the meal in 15th-century Spain.

In Early Modern Spain, Food Had Social Implications

Professor Jodi Campbell dishes on the meaning behind the meal in 15th-century Spain.

The first rule for avoiding an epic food fight? Don’t mess with the seating chart.

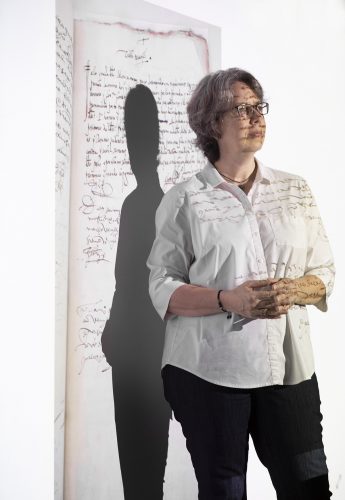

Jodi Campbell, professor of history, researches ways in which early modern Spaniards used food as a means of proclaiming social identity. Photo by Joyce Marshall

For Spaniards in the 1400s to 1600s, scoring a seat at the “first table” with the movers and shakers (the dean, priests and aldermen) indicated they had reached the apex of the societal pecking order.

At the First Table: Food and Social Identity in Early Modern Spain (University of Nebraska Press, 2017) by Jodi Campbell explores how people with certain economic standing, social connections, religious affiliations and regional identities interacted within an evolving society.

“I came across a mention of a spat between two merchants where one told the other, ‘You will eat alone at the table!’ ” said Campbell, professor of European history.

The recording of such an insult raised a question for Campbell. During a sabbatical in Spain, she began to cull university accounts, household ledgers of nobles, monastic records and early recipe books and soon discovered: “Everybody buys food, and it leaves a paper trail.”

As Campbell followed the musty, often stained and sometimes bug-eaten documents, she discovered that food and its corresponding rituals bonded members of Spanish society while simultaneously separating them into hierarchies.

Bread, for instance, was one of the most closely monitored components of people’s diets. Rationing was necessary to avoid social unrest, but it also could serve aspirational goals, both in life and the afterlife.

“While bread was the simplest and most common gift of food to the poor, some took advantage of the opportunity to engage in a greater show of generosity,” Campbell wrote. “A funeral could be perceived as a kind of last-ditch bid for self-improvement, in which one could make a final effort to improve one’s image through a dramatic act of charity.”

Catalan records show a distinction between “fat funerals,” with funds for an impressive family meal and large public displays requiring rented equipment to accommodate crowds, and “thin funerals,” which did not.

Jodi Campbell explores how food and mealtime can reflect economic standing, social connections, religious affiliations and regional identities. Photo by Joyce Marshall

One of Campbell’s favorite chapters to write describes the various uses of bread: as a religious symbol echoing the bread Christ offered to his disciples; as a donation to the poor; as an offering to the dead in the form of edible “tomb buns,” an inexpensive bread similar to a ship’s biscuit that was left at the tomb; and even as a special type of bread offered to those about to undergo torture.

While research into Spain’s food culture has greatly expanded in recent years, Campbell said it is difficult for non-Spanish-speakers to access.

Ken Albala, a professor of history at the University of the Pacific in Stockton, California, contributed a review that appears on the book’s cover. He called it “a phenomenal book … beautifully written and organized, and meticulously researched with a broad range of primary and secondary sources. There is nothing like it in English.”

He added in an email, “I fully expect that this book will draw the attention of both food scholars and early modernists, because it has implications about the social meaning of diet that apply to all human societies.”

Alex Hidalgo, associate professor and director of undergraduate studies in the history department at TCU, said, “Campbell’s interest in power, women, gender and class are all reflected in her study of food.”

The intense labor required to produce a meal before the advent of refrigeration and the rules of communal dining before the invention of the fork were new concepts for Hidalgo. But he was further struck by the “vertical” hierarchies Campbell revealed, such as peasants who dug for turnips and ate pork and other land animals while wealthier monarchs plucked the sweeter, higher-quality fruit from the trees and ate fowl.

“That attention to culture and society is what drives her,” Hidalgo said of his colleague. “When I read the book, I didn’t necessarily think it was about food. It’s through the medium of food that we see how [Spaniards] think about each other.”

“Food is a way to measure generosity and a level of commitment to your community.”

Jodi Campbell

“Food is a way to measure generosity and a level of commitment to your community,” Campbell said. While she takes pains not to call herself a food historian, Campbell found that food was a way into a narrative about how members of society “perform” when they are in public, especially in a time when “people’s reputations are everything. … Everyone was really aware within this community what their status was.”

But are seating charts still relevant in modern America?

Hidalgo chafed at the memory of being seated at the kids’ table at a Thanksgiving celebration when he was in his early 20s. More recently, he said, he understood the peculiar power of a seating chart when he was put in charge of a departmental banquet.

“I think there is still a case to be made about that hierarchy and how the collective consumption of food can still be a highly performative act,” Hidalgo said.

Your comments are welcome

2 Comments

Fascinating work by a brilliant young professor. Proud to have been her colleague. This works illustrates so well how historians are asking new questions of the past and discovering much more nuanced answers about the quality of life lived by those before us. So much more interesting than battles and regnal years. Well done Dr. Campbell!

Jodi Campbell’s research into the social implications of food in 15th-century Spain is absolutely fascinating. The way she delves into the intricate details of how people’s social standing, religious affiliations, and regional identities were intertwined with food rituals provides a unique perspective on the society of that time.

I was particularly struck by her exploration of the significance of bread and how its distribution was not just about sustenance but also about social hierarchy and aspirations. The notion that even something as basic as bread could be a symbol of generosity and a way to improve one’s image is truly intriguing. It’s amazing how these historical practices around food still resonate with our understanding of community and identity today.

Additionally, Campbell’s observations about communal dining and seating arrangements are thought-provoking. The idea that the way people share meals and organize seating can reflect power dynamics and social order is a concept that still holds relevance in our modern world. It’s incredible how food, something so essential to our daily lives, carries such profound cultural and social significance.

Overall, Campbell’s work not only provides valuable historical insights but also prompts us to reflect on our own cultural norms related to food. Food is not just a means of nourishment; it’s a lens through which we can examine the complexities of human relationships and societal structures. Campbell’s research is not just a study of the past; it’s a profound exploration of the human experience.

Related reading:

Features

Food Justice Class Shines Light on Hunger, Nutrition

Community gardening, interviews and delivering nourishment to food deserts are all part of the curriculum.

Features, Research + Discovery

Komla Aggor Traces Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Through Language

Descendants of African slaves use the Spanish language to understand their history in Latin America.

Campus News: Alma Matters

Class explores booming Spanish-language media

Since 1980, the U.S. Hispanic population has grown from 14.6 million people to nearly 52 million, and TV ratings and circulation figures are showing the impact.