Careers of Federal Workers Tell Story of Racism

Frederick Gooding Jr. looks at how integration of the workforce hid years of continued discrimination.

Careers of Federal Workers Tell Story of Racism

Frederick Gooding Jr. looks at how integration of the workforce hid years of continued discrimination.

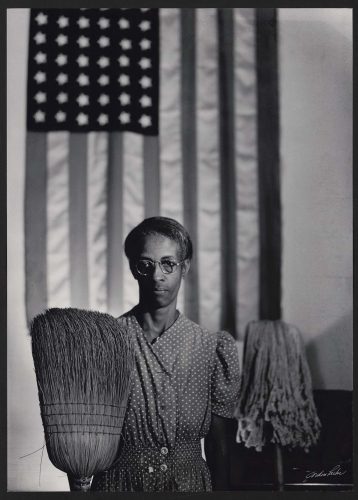

Ella Watson is the subject of “American Gothic” (1942). Frederick Gooding Jr. used the photo of the Farm Security Administration janitor on the cover of his book about inequities in the federal workforce. Courtesy of Library of Congress | Photo by Gordon Parks

In a polka-dot dress with missing buttons, Ella Watson stands with a worn straw broom in front of an American flag. The African American’s empty gaze and slight slouch give the impression that she is just as tired as her dress and broom.

This photograph of Watson — Gordon Parks’ 1942 “American Gothic” — landed on the cover of a book by Frederick Gooding Jr., assistant professor of African American studies in the John V. Roach Honors College.

American Dream Deferred: Black Federal Workers in Washington D.C., 1941-1981 (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2018) is Gooding’s exploration of black federal workers’ struggles to integrate into a working class that had excluded them.

Gooding discovered that Watson, a widow, earned an annual salary of $1,080 that she used to support herself and her deceased daughter’s three children, one of whom was disabled. By the time Watson was photographed at work, the Farm Security Administration janitor had been employed by the government for 25 years.

Watson scored higher in an initial performance rating but received less pay than a white female colleague and didn’t advance at the same rate, although the two had the same level of experience.

Gooding’s research found that American society tends to put a mask on racism, creating the illusion that discrimination has lessened in severity. But that’s not true. “Things are consistent over time,” Gooding said. “That’s the more sobering message.”

As the predominantly white male workforce marched off to war, gaps were left where black Americans could step in and gain a foothold in society. “Black-collar workers,” a term Gooding coined, were available and willing to accept low-paying federal positions.

Frederick Gooding Jr., assistant professor of African American Studies in the John V. Roach Honors College, has a new book: American Dream Deferred: Black Federal Workers in Washington, D.C., 1941-1981 (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2018). Photo by Joyce Marshall

This created “an integrated workforce that was kind of forced upon people,” Gooding said. Segregated environments were still standard practice, but the door had opened for black Americans to achieve better job stability. For the first time, African Americans had a chance to become middle-class participants.

But while those federal workers at the time may have gotten job stability and benefits, many were “still magically stuck in these lower-paid positions,” Gooding said. It would take them years to get promoted.

Hoover Rowel was a landscape worker vying for a promotion from Grade 4-level government pay to Grade 5. Federal jobs have 16 grades, with any job below Grade 8 being considered low- to mid-level range.

Rowel had to wait 19 years for that promotion.

“Racism takes the shape of its container, just like water,” Gooding said. In these situations, Gooding said, African Americans had “to pay to play” and tackle new discriminatory tactics like those experienced by Watson and Rowel.

“No matter the policy, no matter the new groundbreaking change or rule, we see how African Americans still end up suffering from this idea that they’re not being valued, and they’re not being paid their full worth,” Gooding said. “That’s a larger chronic issue.”

“How do you tackle this random abstract perception that African Americans are just not worth it and just not good enough?”

Frederick Gooding Jr.

Lucille Mercer, another African American postwar federal employee in Washington, D.C., worked for seven agencies. She started at the U.S. Census Bureau in 1950 and moved on to become a keypunch operator for the CIA and to travel to Uganda while working for the U.S. State Department.

With only a high school diploma, she was able “to have a full and varied career with the federal government,” said Joye Mercer Barksdale, Mercer’s daughter. “I’m sure she wouldn’t have found the same opportunities with the private sector. Not in that era.”

Barksdale said her mother loved her work, but there was “frustration when she would apply for a position she wouldn’t get and then she would end up having to train the person who did get the job.”

Gooding’s research points to the idea that discrimination evolves over time.

“How do you tackle this random abstract perception that African Americans are just not worth it and just not good enough?” Gooding said. “Many of us, despite being well-intentioned, still suffer from a lack of three key pieces: a lack of experience, a lack of exposure and a lack of education.”

Without these, Gooding said, “You’re possibly doomed to repeat some of the mistakes of the past.”

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related reading:

Research + Discovery

Black Theater and Literature Show America’s Painful Past

Stacie McCormick, assistant professor of English, explores the link between slavery and contemporary African American performance and literature.

Alumni

James Chase Sanchez’s Documentary Airs on PBS

Documentary filmmaker and alumnus wins an award for Man on Fire.

Research + Discovery

Ideas of Terrorism Transfer to Latin American Immigrants

A sociologist finds the unease affects U.S. views and laws.