The coronavirus pandemic steamrolled many companies in 2020, while others found new solutions to the supply chain disruption. Photo by Christina Gandolfo

Forging a New Supply Chain

Covid causes companies to adapt to supply and demand swings.

Shoppers adore Half Price Books’ cavernous flagship store in Dallas. They may arrive looking for Tana French’s latest mystery and leave with a Korean cookbook, vintage vinyl and a children’s board game.

Such treasure hunts came to a halt when the retailer temporarily had to close more than 120 stores in 17 states this spring to comply with state orders intended to stem the spread of the coronavirus.

Although Half Price saw a record number of online shoppers after enabling consumers to search for and buy items like mugs, T-shirts and tote bags in addition to books, online sales typically account for only about 10 percent of total revenue.

Even as the pandemic caused the Dallas-based company’s total gross sales to decline about 13 percent for fiscal year 2020, which ended June 30, it managed to turn a profit, said chief strategy officer Kathy Doyle Thomas ’79. In the early part of fiscal year 2021, the company saw revenue decline 25 to 30 percent. But it is seeing steady sales increases and hopes to remain in the black.

Kathy Doyle Thomas, executive vice president for Half Price Books, saw the company’s revenue dip 25 to 30 percent in the early part of the 2021 fiscal year. Photo by Ross Hailey

“We are being conservative and we are being cautious, and that’s how we’re staying in business,” Thomas said. “Every retailer is being smarter.”

Scenes of alternately full and sparsely stocked warehouses — and the ramifications for businesses’ bottom lines — have been repeated across the country as what started as a public health crisis spiraled into the nation’s worst economic downturn since the Great Depression. The speed at which the dual health and economic crises unfurled is unprecedented. The virus first identified in Wuhan, China, in December 2019 landed in the United States in January, and the U.S. economy was in recession by February.

The coronavirus pandemic and the measures taken by the United States and other countries to contain it upset the flow of materials and goods — from suppliers to manufacturers to retailers to customers — in a time-honored process called the supply chain.

Workers became ill. Factories shut down. Port and air cargo stood still. Raw materials and finished goods piled up on loading docks and in warehouses. Companies couldn’t get supplies, resulting in unfinished laptops and lawn mowers. Essential goods — everything from toilet paper to chicken — disappeared from store shelves. Many businesses closed. At one point, over 31 million people collected some form of unemployment benefits.

Experts expect supply chain disruptions to continue well into next year, meaning more items occasionally may be out of stock at neighborhood shops. Although the Federal Reserve projects the U.S. economy will start to rebound in 2021, negative effects will echo far longer in terms of unemployment, business health and supply chain disruptions.

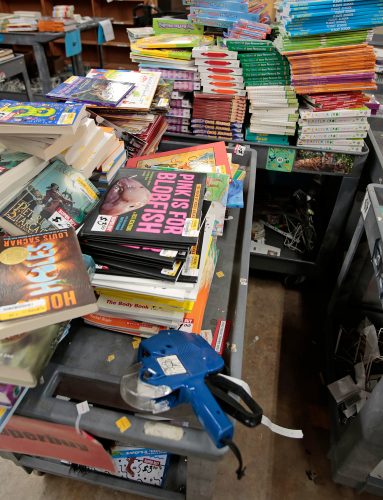

Companies like Half Price Books experienced disruptions in the supply chain. Photo by Ross Hailey

Never before has the importance of supply chains become so clear.

In the future, how goods are ordered, made, stored and delivered will look far different than those processes did before the pandemic.

The highly synchronized global supply chain that most U.S. companies have been driving toward for decades is taking a sharp turn. Instead of zero waste and just-in-time systems, companies will keep more inventory nearby, said Laura Meade, professor of supply chain practice at the Neeley School of Business.

Zero waste and just-in-time delivery are key elements of the “lean” system created by Toyota to make cars decades ago. That system, which has expanded beyond manufacturing to delivery, management and the service sector, uses efficient processes and only the number of goods needed for a particular production process — called just-in-time inventory — to reduce waste, increase productivity and cut costs.

Over the last few decades, this approach has led companies from Amazon to Nike to seek low-cost suppliers and manufacturers, often in other countries. But now, instead of locking in a supplier in, say, China, companies will seek multiple suppliers in multiple places to respond more quickly to sudden market changes.

The supply chain of the future will be more localized and automated, Meade said.

“The survivors are going to be the ones who are able to shift and respond to new market demand.”

Laura Meade

“The survivors are going to be the ones who are able to shift and respond to new market demand,” she said. “Manufacturing will shift from just-in-time to just-in-case for a while. Covid is giving companies the opportunity to experiment with what the supply chain should be, based on what is needed.”

Uncertainty Reigns

Businesses are grappling with questions about what is essential to a new supply chain model under a cloud of uncertainty: Will the virus resurge? When will a vaccine be ready for the public? What are the ramifications of the November presidential election?

John Harvey, professor and chair of economics at TCU and a frequent contributor to Forbes, noted that uncertainty has a paralyzing effect on people, businesses and the economy.

“It turns out that firms’ investment spending is an extremely critical part of [gross domestic product],” he said. “Right now, why on earth would anyone invest with all of these things against it?”

A lack of business investment combined with less consumer spending helped drive the plunge in the nation’s economic output, down a record 31.4 percent from April to June.

Forced business closings were designed to help curb the spread of the coronavirus, but they also hurt individual businesses and the overall economy. And the unpredictability of the situation made planning for the future difficult.

Kathy Doyle Thomas, executive vice president for Half Price Books, said there was much uncertainty surrounding how long stores would be closed because of Covid-related business restrictions. Photo by Ross Hailey

“When you examine what you did months ago, you have to understand we didn’t know how long we would be closed [or] if we would be out of business in three months. We didn’t know what the future would hold,” said Thomas of Half Price Books. The company’s stores reopened starting in May, but with occupancy limitations and threat of a second shutdown. They were fully reopened with limited hours by late June.

Through the Paycheck Protection Program, the Federal Reserve’s Main Street lending program and other financial aid, the government has made hundreds of billions of dollars of credit available to businesses. The Fed also has pledged to keep interest rates low and make credit available to ailing businesses until the economy recovers.

Andrews Tool Co., an Arlington, Texas, supplier of portable power drills and other equipment to the aviation and aerospace industries, received a paycheck protection loan in March, said owner Sol Kanthack ’94. The funds did what they were intended to do: The company didn’t furlough or lay off any of its half-dozen employees.

“We started the year very strong, with orders in the pipeline through April,” said Kanthack, who has witnessed a third of his business (to Boeing) drop by about a third this year. “In June and July, [it was] a lot slower. I don’t see what’s going to change in a major way, so you just have to adjust your business model.”

A Wobbly Wheel

Think of the supply chain as the hub-and-spoke system of a giant wheel, with raw materials and parts suppliers, manufacturers, shippers and customers connected through transportation, storage and storefronts along the way. The pandemic damaged some of those spokes, causing the wheel to wobble.

Jason Gameros uses a forklift to retrieve a pallet from the top shelf at the NFI warehouse in north Fort Worth, where boxed goods for grocery stores, pharmacies and large retailers are stored and shipped. Photo by Rodger Mallison

In May, 97 percent of businesses surveyed by the Institute for Supply Management said they had been or expected to be affected by disruptions extending through the end of the year. As a result, more than three-quarters reduced their revenue targets, nearly two-thirds planned to reduce their capital expenditures, and about one-third planned to reduce worker hours or cut staff.

“This is a watershed moment that will change the way companies think about supply chain,” said Thomas Derry, CEO of the Institute for Supply Management. “The fundamental reason is still about being able to run a business effectively and efficiently, but the global supply chains that exist today are too disruption-prone.”

The global wheel revolves around supply and demand. At the beginning of Covid-19, supply couldn’t keep up with demand. Massive surges in demand for goods such as toilet paper and hand sanitizer, combined with production and delivery disruptions, resulted in a shortage of those products.

During the summer, the chain was plagued by more of a demand problem, with U.S. consumers spending less money because of record unemployment, closed businesses and travel restrictions. People haven’t bought many suits, belts or fancy restaurant meals.

Roughly three-quarters of business executives said their July revenue was down compared to a typical year, and nearly two-thirds blamed it on weak demand, according to a survey by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

Complicating matters is that supply and demand keep fluctuating, with declines and surges happening simultaneously.

Now the wheel has completely fallen off, creating havoc from end to end in the supply chain.

John Moore III is a fourth-generation farmer at his family farm in Arvin, California. Photo by Christina Gandolfo

John Moore III ’12, vice president of his family farm near Bakersfield, California, is familiar with the duality of supply and demand. He sees it every day as he drives with dogs Cal and Charlie across 1,000 acres of green fields of root vegetables and flowering nut trees reaching almost to the Tehachapi Mountains.

Moore has seen demand increase for the specialty potatoes Moore Farms grows for Frito-Lay potato chips as people stay home and eat more comfort food during the pandemic, he said. The fourth-generation farmer sold 10 percent more potatoes this year to Frito-Lay and hopes to negotiate a larger contract for next year.

His almonds are a different story. Many of the nuts are exported to places like India, the top export market for California’s $5.5 billion almond industry.

“India goes through an incredible amount during their festivals,” Moore said. “Lockdown orders have affected demand for almonds, and some international buyers have defaulted.”

At Moore Farms, potatoes are loaded into trucks, covered and transported to a washing facility. Photo by Christina Gandolfo

Such export troubles combined with a projected record California almond crop this year have caused commodity prices for almonds to fall by about $1 a pound since January to roughly $1.50 in August. That decline will affect farmers’ profits and could lead to an oversupply that further depresses prices, said Moore, who also is president of the Kern County Farm Bureau. Kern is one of the top almond-producing counties in California, which produces 80 percent of the world’s supply.

In response to uncertain supply and demand, some companies are trimming their product options to streamline operations and focus on the most profitable sellers. This simplification means consumers might find Lysol spray, but not the lemon-scented kind, or Coke Zero, but not Diet Coke with Splenda.

Companies must ask themselves if they’re experiencing a temporary surge in demand, said Derry of the Institute for Supply Management. “Do I invest in temporary demand? When we get a vaccine, and people feel safer and people have a couple of pallets in their garage, will demand fall?”

The Resilience Trade-off

If “lean” had been the driving force since the 1980s, now the buzzword is “resilience.”

While many companies have adjusted to a new normal during the pandemic — think Office Depot selling face masks next to printers — lessons can be gleaned from how resilient companies fared in the last recession in 2008-09, experts said.

Research on 1,800 companies by Morgan Swink, executive director of TCU’s Center for Supply Chain Innovation, found that resilient companies in the 2010 recovery grew faster, with 12 percent higher return on assets, 4 percent higher sales and a third more market capitalization (the stock market value of a publicly traded company’s outstanding shares). Swink’s research led him to develop some key principles to build a resilient supply chain, including centralizing and localizing operations, cross-training employees for flexibility and monitoring inventory in real time.

John Moore III conducts business from his tailgate during harvesting at Moore Farms in Arvin, California. His dogs Cal and Charlie are usually at his side. Photo by Christina Gandolfo

While resilience may make companies more adaptable when faced with market disruptions, their supply chains may become less efficient in the short term.

“The question is how we will pay for a lack of efficiency,” said Swink, who also is the Eunice and James L. West Chair of Supply Chain Management. “We’re paying for the lack of resiliency now. You pay for it either way. The challenge is to get [corporate executives] and the general public to recognize the value of resilience, which is a capability that doesn’t have value until it’s called for. It’s like insurance.”

What’s on the Shelf

Lean systems help companies reduce waste, so the foam tongues for sneakers are bought just in time during the manufacturing process to avoid tying up space and money. But such lean inventories left many businesses with insufficient supplies to meet unexpected surges in demand during the pandemic.

“Inventory has been viewed as an evil excess thing, but Covid-19 has highlighted the weaknesses of a lean system,” Swink said.

Many lead times, the gap between a manufacturing order and the finished product, doubled through May, according to Institute for Supply Management research. In addition, uncertainty about demand drove nearly half of surveyed companies to hold more inventory than usual.

Brian Gallegos scans the barcode on a pallet as he uses a forklift to load a truck at the NFI warehouse in north Fort Worth. Photo by Ross Hailey

Fort Worth-based Shoppa’s Material Handling saw shipments of the Toyota forklifts it sells delayed for up to 45 days after Toyota factories shut down temporarily during the pandemic, said owner Jimmy Shoppa ’80. Its excess pre-coronavirus inventory quickly became insufficient.

The $225 million, 450-employee company let customers borrow forklifts from its fleet of 2,000 rental units until their orders could be filled. But Shoppa knew he needed a better long-term fix.

“We’re having to adjust our business to [meet] our customer needs,” he said. “As a business owner, you’re trying to make decisions based on data. It’s definitely a time of transformation.”

Shoppa is working with TCU’s Center for Supply Chain Innovation to enhance its systems to better forecast and track inventory and hopes to use that information to improve supplier and customer relationships. Reordering parts, for example, will be easier and more accurate when they are labeled correctly and not entered into the database more than once, which can lead to inventory and order fulfillment problems.

“As a business owner, you’re trying to make decisions based on data. It’s definitely a time of transformation.”

Jimmy Shoppa

TCU students are helping to audit the company’s data — from parts numbers to active customers — to make sure the numbers are always updated and accurate for speedier and smoother fulfillment.

Shoppa isn’t alone. ABI Research, a New York-based global tech market advisory firm, forecasts North American corporate spending on supply chain planning software will grow from $1.4 billion in 2019 to $1.9 billion in 2024.

On the Move

For three decades, U.S. companies have looked across the globe for lower-cost supplies and manufacturing. But experts say Covid-19 has accelerated a retreat from such globalization — dubbed “slowbalization” by some — that began about a decade ago thanks to higher tariffs and protectionist trade policies.

Now U.S. companies are localizing their supply chains to focus on what’s called “the last mile,” ensuring customers get what they want when they want it and where they want it.

Companies also are doing more of the work they used to outsource and are bringing some foreign manufacturing closer to home, such as from China to Mexico or even back to the United States, to be more agile.

But this shift in supply chains is a complex process that can take years to complete as companies wait for existing contracts to expire, find new partners or negotiate new contracts.

Kathy Doyle Thomas said deliveries to Half Price Books idled at Chinese ports because of the pandemic. Photo by Ross Hailey

Containers full of jewelry-making kits and assorted toys bound for Half Price Books’ central distribution center in Dallas were delayed several months as they idled at Chinese ports. Even as those goods, intended for Christmas, finally began to arrive stateside, Half Price found itself in a quandary.

“We have to accept the stuff from China, even though we might not sell it during the holiday season if there is another shutdown, even if we need to find more warehouse space or resell it,” Thomas said. “We can’t afford to stop the supply chain completely because we need supplies for the stores. We have to keep inventory coming.”

Typically, Half Price would try to sell leftover holiday goods at giant post-Christmas sales, but this year the company won’t hold such sales because of social-distancing measures.

Such shipping issues combined with new tariffs on Chinese goods have spurred Half Price to seek U.S. vendors. Already it has found a U.S. manufacturer for turntables that were hot sellers last Christmas, Thomas said.

Nowhere is de-globalization more evident than in manufacturing. ABI Research expects coronavirus-induced shocks to substantially reduce the $15 trillion in global manufacturing revenue it forecast for 2020.

“Not enough firms had a Plan B or C.”

Susan Beardslee

Susan Beardslee, a principal analyst for ABI, said she expects supply chain disruptions well into next year. “It has been a wake-up call for companies,” she said. “Not enough firms had a Plan B or C” and continued to follow their same cost, sourcing and other strategies.

Andrews Tool Co. just shifted some of its manufacturing from Chicago to a company called Mozaic a couple of miles away in Arlington, Texas, a move Kanthack estimates will save at least tens of thousands of dollars in shipping costs and one to two weeks in delivery time.

Mozaic is shifting some of its production of cushions and pillows from Asia to Mexico to shorten delivery time and avoid uncertainty over doing business in Asia, said owner Patrick Lane. The 70-employee company also is considering dual sourcing — having two sources for one component — for as many products as possible, he said, “so if one supplier shuts down, our business will not be damaged.”

More U.S. companies are moving toward multiple suppliers in multiple countries in hopes that such diversification will make them more resilient. But increased agility and a move away from the lowest-cost countries for production may require other changes to operations.

“If we bring [manufacturing] back home,” TCU’s Meade said, “it will have to be automated to keep costs low.”

Technology to the Rescue

During the summer nut harvest, wireless sensors in the soil and on plants help California farmer Moore irrigate just enough during temperatures that often top 100. He even gets readings on his phone while he tends to the farm.

“Crises like Covid show you can’t bank on high commodity prices,” Moore said. He began investing in technology such as precision irrigation a few years ago, and now “price swings have justified it and made it a necessity” to increase yields, he said.

While industries such as agriculture and auto manufacturing have used technology for years to improve performance and control costs, others are just dipping their toes in big-data waters.

Covid-19 has accelerated the race for companies to embrace artificial intelligence, robotics, drones and more to better predict and handle supply chain disruptions.

Jimmy Shafer, NFI senior vice president for solutions, design and engineering, said the company had to shift gears and reallocate warehouse space. Photo by Rodger Mallison

NFI Industries, a New Jersey-based company that provides transportation, distribution, port and logistics services, is using business intelligence, robotics and other technology to adapt more quickly to changes within its supply chain and among diverse customers nationwide.

During the pandemic, some NFI customers such as clothing retailers were required to restrict operations, while others in essential industries such as fresh food saw demand spike as much as 40 percent, said Jimmy Shafer ’03 MBA, NFI’s senior vice president for solutions, design and engineering.

The company was able to quickly shift gears, redirecting some of its over 50 million square feet of warehouse space, 3,000 trucks and 13,100 employees to meet changing needs. For example, inside two weeks, NFI opened a fulfillment center for a large e-tailer to distribute hand sanitizer and wipes, Shafer said. It also reallocated trucks and used one of its own warehouses to help a large beverage maker move can supplies from Florida to a factory in the Northeast.

One NFI customer, a large baked goods manufacturer, used to donate its excess products. During Covid-19, NFI employed new processes and scheduling to help the bakery get its bread to stores that needed to fill empty shelves.

“What we learned in Covid-19 is that we want to track [data] in seconds,” said Shafer, whose team designs and runs what-if scenarios. “We’re on the road map to real time.”

NFI has implemented technologies using artificial intelligence and sensors on trucks to collect real-time data to predict maintenance requirements, Shafer said. NFI wants to use sensors and advanced shipment visibility to map and monitor operations in real time to promote safety, optimize operations and send alerts to drivers based on conditions like weather.

The pandemic has created an opportunity for some companies to consider new strategies, such as entering new markets or acquiring smaller companies, and perhaps set the stage for growth and increased profitability.

“During times of crisis, companies with financial flexibility have the opportunity to expand or buy companies at really good prices or take market share away from competitors.”

Thomas Moeller

“During times of crisis, companies with financial flexibility have the opportunity to expand or buy companies at really good prices or take market share away from competitors,” said Thomas Moeller, associate professor of finance at TCU, who specializes in corporate finance.

Earlier this year, Fort Worth business owner Shoppa stepped up when he realized many of his customers’ needs were changing. His company, which also sells warehouse equipment such as sweepers and aerial lifts, began to offer warehouse design services, and it is expanding into the battery and tire businesses.

“There will be winners and losers,” said Shoppa, who is preparing for a future where companies want more automation, prefer to lease equipment and request on-site equipment servicing. “Everything we’ve done during this pandemic is about making our business better, and I think we’ll come out of this stronger and more effective.”

For Thomas of Half Price Books, the pandemic has provided time to complete some back-burner projects that may boost sales and make a difference to the company’s long-term survival.

Customers may notice they now can search for books on Half Price’s website by store location, a back-end feat accomplished in four days, Thomas said. And as of mid-July, they can search the website for thousands of new products, such as puzzles and board games.

“We started doing projects that we always wanted to do,” Thomas said. “We can be more creative in trying new things.”

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related reading:

Campus News: Alma Matters, Research + Discovery

Factoring Humanity and Happiness into Economic Calculations

In a Q&A, Rob Garnett, professor of economics, honors professor of social sciences and associate dean in the John V. Roach Honors College, combines economics with happiness.

Alumni

A Helping Hand for Shoppa’s Material Handling

Business owner looks to TCU’s Center for Supply Chain Innovation for solutions.

Web Extras

Kathy Doyle Thomas Talks Supply Chain

Covid-19 drastically shifted the way businesses operated, including Half Price Books.