China and Russia’s Relationship: A Q&A and Timeline

Carrie Liu Currier and Kiril Tochkov discuss trust, differences and rivalry between the two superpowers.

China and Russia’s Relationship: A Q&A and Timeline

Carrie Liu Currier and Kiril Tochkov discuss trust, differences and rivalry between the two superpowers.

What impact could the partnership between China and Russia have on the United States and its interests abroad?

TOCHKOV: During the past 70 years, China and Russia have emerged as the key competitors of the United States on the world stage. During the Cold War, the two countries, and especially their alliance, represented a major military and ideological threat to America and its global strategic interests. Since the 1990s, the geopolitical rivalry has been complemented by economic concerns as globalization deepened trade and investment ties. China has turned gradually into an economic superpower that dominates manufacturing and trade, while an increasingly authoritarian Russia has been trying to revive its military might through involvement in conflicts around the world.

Currently, we are standing at the threshold of a new era marked by a growing clash between the U.S. and the strategic alliance of Russia and China. Trade with China is often blamed for the loss of manufacturing jobs and the increase in the income inequality in the U.S. Russia has emerged again as one of the main geostrategic threats to the U.S. in a new version of the Cold War.

A deeper understanding of the relations between China and Russia will allow policymakers to devise strategies in containing the rivalry with these two countries from turning into trade wars and military clashes that would be detrimental to the U.S. and its partners around the world.

Kiril Tochkov, associate professor of economics, and Carrie Liu Currier, associate professor of political science and director of Asian Studies, launched an interdisciplinary research study on the implications of the strategic partnership between China and Russia. The professors are looking at the benefits and drawbacks of the union as well as the complications inherent in the merger of two different political systems. Photo by Carolyn Cruz

Is the current Sino-Russian partnership a temporary marriage of two countries seeking to strengthen their global influence or a fundamental shift in world power?

CURRIER: With Russia and China it is always a temporary relationship. They each are interested in preserving domestic stability in their own countries, and their approach to foreign policy is one that clearly reflects their own changing self-interest. … In many respects, the things they have in common involve a distrust of the United States and dislike for U.S. policies/intervention abroad. The real threat the Sino-Russian alliance poses is a sense of growing economic strength independent of the West and a counterbalancing force to Western interests globally.

What are some of the key differences in what China and Russia want from each other?

TOCHKOV: China remains fixated on economic issues and is interested in expanding its trade with and investment in Russia. In contrast, the Russian government has been preoccupied with national security concerns and has been keen on restoring its global clout on the international stage at the expense of reforming its domestic economy and making it more competitive. Despite a slowdown, China’s economy continues to grow, creating demand for natural resources. Russia has not been able to diversify its economy, which still largely depends on exports of oil, gas and natural resources. Western economic sanctions and the steep decline in oil prices have devastated the Russian economy, compelling the government to seek alternative markets in East Asia and to offer major concessions in negotiations with China.

What challenges could undermine the current Sino-Russian alliance?

CURRIER: The Chinese ultimately have no true allies, and the greatest concerns for Chinese leaders are maintaining economic stability. It is possible that Russia and China can find themselves at odds economically, as there are already commercial challenges in border regions. And there is growing concern in Russia [and globally] with regard to how the Chinese do business and the massive influx of goods coming from China. When push comes to shove, both states know the partnership is volatile.

TOCHKOV: The lack of trust between the two countries is a major stumbling block for deepening economic ties. China has the financial funds, the labor and the technical know-how to foster economic development in Russia, especially in the economically depressed regions of Eastern Siberia and the Russian Far East. However, the Russian government is very reluctant to encourage such cooperation because it does not want to turn Russia into a cheap supplier of commodities to China.

In addition, Russians are fearful that China can establish its economic dominance in border regions that have been traditionally part of the Chinese empire. As a result, Chinese workers and companies are facing various hurdles when trying to do business in Russia.

— Mary Ann Kurker

Cooperation and Conflict through the Years

From friendship to the brink of war, the partnership between China and Russia has always been fickle. A research project examines how cooperation between the countries hinges on their economic and political views being in sync. TCU experts in political science and economics joined forces to analyze five distinct periods in Sino-Russian relations over six decades (1950-2010).

1950s:

Fast Friends

Chinese leader Mao Tse-tung, left, and Nikita Khrushchev visit during the Russian leader’s 1958 trip to Peking (Beijing). Public Domain photo

China quickly aligns itself with the Soviet Union on the heels of the Chinese Revolution. The birth of the Chinese communist state is in near-perfect alignment with Russian political and economic ideologies:

• Both countries strive for an ideal communist society, adopting the principles of Marxism and Leninism.

• State economies in China and Russia operate without free-market mechanisms.

• Mutual economic help and intensive cultural exchanges mark the era. Russia sends tens of thousands of Soviet engineers and technicians to build China’s infrastructure and promote industrialization. In a massive influx, Chinese students arrive in the Soviet Union.

• The friendship begins to crumble in the late 1950s as China’s leadership becomes frustrated with the slow pace of industrialization and starts the Great Leap Forward to elevate its economy. Russia is at odds with this and envisions gradual growth through five-year plans.

1960-1984:

The Big Chill

The mutual embrace of communism was not enough to sustain political relations between China and Russia during the Cold War. Getty Images © TPOPOVA

Mutual mistrust and a fiery ideological rift lead to a bloody border conflict:

• Russia is at a standoff over China’s desire to expand into a huge communist economy — mobilizing millions of people in a short time.

• The rift prompts Soviet engineers and technicians to pull out of China in 1960, leaving many joint projects unfinished.

• A territorial dispute over Zhenbao Island, on the far eastern border of Russia and China, leads to military conflict in 1969. Hundreds of soldiers on both sides of the border are killed.

1985-1991:

Arm’s Length

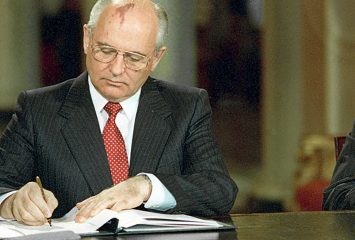

Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev in 1990. Russian International News Agency (Ria Novosti)

Cooperation is gradually restored as a Russian reformer, Mikhail Gorbachev, tries to mend relations with China:

• After years of inefficiencies, Chinese and Soviet leaders realize the need for deep economic reforms. They create new economies based on market principles, while still holding a monopoly on power.

• In 1985, Gorbachev’s Soviet reforms foster a stronger alignment with China, in both political and economic ideologies.

• The breakdown of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the emergence of Russia, where the communist party was banned, introduce new frictions between the two countries.

1992-1999:

Clash of the Titans

Economic ideologies are in sync but political ideologies clash, preventing China and Russia from restoring close ties:

Economic ideologies are in sync but political ideologies clash, preventing China and Russia from restoring close ties:

• Both countries advance their market-based economies. China is becoming a global supplier of cheap goods, while Russia is struggling to reform its local industry and retain global economic clout.

• Despite harmony in market ideologies, the gap widens on the political front. Russia is interested in Western reforms, while China clings to communism.

• The transition toward a democratic society in Russia clashes with the brutal suppression of dissent in China.

2000s:

Close Comrades

Russian President Vladimir Putin, right, presented the Order of St. Andrew the Apostle to Chinese President Xi Jinping on July 4, 2017, at the Kremlin in Moscow. Photo courtesy of Creative Commons | Kremlin.ru

The partnership between China and Russia reaches new heights. United by a mutual appreciation for strong leadership, they defend their national interests while challenging Western dominance. China and Russia also share a new model of state capitalism with limited political freedoms:

• China is not critical of either Russia’s aggression in Syria or Russia’s annexation of Crimea in Ukraine — two moves sharply condemned by other world leaders.

• As Western sanctions over its actions in Ukraine unfold, Russia turns to China to ensure a market for its hydrocarbon exports. Both countries agree to build a natural-gas pipeline for Russian crude oil into China and the first bridge connecting their borders.

• Russian President Vladimir Putin reverses many of the reforms of the 1990s and introduces his system of “managed democracy” in Russia, with a greater role for the state in economic matters.

• The two countries deepen their economic and political ties and join the elite club of emerging economies known as BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa).

Sources: Interviews with Kiril Tochkov, associate professor of economics, and Carrie Liu Currier, associate professor of political science and director of Asian Studies at TCU. “Ideology and the Turbulent Nature of the Strategic Partnership Between China and Russia: An Interdisciplinary Perspective,” grant application by Tochkov and Currier.

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related reading:

Features

Professors Track China-Russia Alliance

A new research initiative illuminates six decades of Sino-Soviet relations to help predict future patterns.

Research + Discovery

Germán Gutiérrez Believes in the Power of Music

The director of orchestras at TCU says music is a way for people to work together and put aside political differences.

Features

Warrior for Peace

Nobel laureate Leymah Gbowee mobilized women to demand an end to Liberia’s second civil war.