Under exposure

Documentarian David Redmon ’95 makes movies most people don’t want to see. But should.

Under exposure

Documentarian David Redmon ’95 makes movies most people don’t want to see. But should.

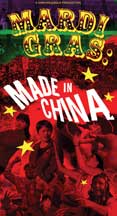

With MTV’s $9.5 million purchase of Craig Brewer’s Hustle & Flow winning the hype wars at 2005’s Sundance Film Festival, what are we to make of a 72-minute documentary about a plastic bead manufacturing plant in the Far East?

Plenty, it turns out.

The world premier at Sundance of Mardi Gras: Made in China garnered more than just decent reviews from The New York Times and the Village Voice – a handful of art house magnates offered distribution deals.

The world premier at Sundance of Mardi Gras: Made in China garnered more than just decent reviews from The New York Times and the Village Voice – a handful of art house magnates offered distribution deals.

But first-time director David Redmon ’95 turned them all down, even though without a distributor it would take a heap of elbow grease to get his debut film noticed. That, or he’d need an alternative to theatrical release.

He went the latter route and threw his shoestring-budgeted documentary to the festival circuit, where it created ample buzz at film series in Amsterdam, Milan, Prague, Istanbul, Seoul and all over the U.S. With so much exposure, Mardi Gras took the academic community by storm.

Six months after Sundance, Redmon started selling DVD copies at $300 a pop. Duke, Yale, Princeton, Cornell, even the University of Western Australia, among dozens of institutions, have bought and shown the film on campus. In November, Redmon said they hoped to sign with California Newsreel to distribute the film to educational markets, which will make it available through Netflix.

The genesis of this indie gem, which has filled theaters with movie nerds and highbrow scholars for almost two years, can be summed up in three words: Bourbon Street flashers.

Armed with a Canon GL1 camera, the director and his producer/girlfriend, Ashley Sabin, cruised through New Orleans’ French Quarter during carnival and captured American tomfoolery in its primal state: a wealth of inebriated twentysomething females showing their breasts for strings of shiny beads, while ogling males encourage the tradition with wolf whistles. This likely wouldn’t merit a university screening, but the Girls Gone Wild gimmick isn’t even half the story.

When Redmon asks the revelers if they know where the beads come from, he gets a blank look. So begins his “cultural exchange program,” a segue to the Tai Kuen bead factory in Fuzhou, China, where approximately 500 workers spend at least 12 hours a day inside a backbreaking sweatshop.

The young women, ages 15-20, live in the Tai Kuen compound, get paid 10 cents an hour and see their families once a year. They don’t know, nor do they care, where these beads are shipped, or who uses them for what.

When the girls see photographs of the rowdy holiday for which they provide millions of plastic party favors, they squeak out a few giggles. All they really want is for their profiteering owner, Roger Wong, to lighten up on the work hours and raise the pay. And if he wouldn’t dock a worker’s pittance remittance for not meeting her daily bead quota, that’d be nice, too.

Though Mardi Gras is not overtly biased, Redmon didn’t want it to demonize Wong in the mold of Wal-Mart: The High Cost of Low Price or the IBM sucker-punch film The Corporation. “It’s just too easy to generalize people like that,” he says, so he kept the narrative as centrist as possible. In response, some critics have characterized the evenhanded stance as cowardly.

Redmon may not agree with the way Wong does business, but he respects him as an individual. Besides, the filmmaker didn’t want any expose of an Asian bead mogul to diminish the real thrust of Mardi Gras: to indict both the consumer and the avaricious business owner for contributing to a socially irresponsible capitalist system.

Redmon was no social butterfly at Texas Christian University. He attended Tarrant County College and Texas Wesleyan University before transferring to TCU, where he soon developed a cynical attitude toward what he considered the country club culture.

Redmon was no social butterfly at Texas Christian University. He attended Tarrant County College and Texas Wesleyan University before transferring to TCU, where he soon developed a cynical attitude toward what he considered the country club culture.

Even the brainy independents intimidated him. “I just didn’t fit in,” he said.

He admits to being an antagonist, picking fights on the soccer field and in the classroom with (presumably) rich kids. As the negativism eventually softened, he became curious about how this different class lived. The neo-Marxist writings of C. Wright Mills, particularly the criticisms on the “power-elite,” inspired Redmon to come to terms with his aggressiveness toward his privileged classmates and might explain his empathy toward Wong.

Redmon learned to see both sides of the class issue. One Thanksgiving he broke bread with a homeless family; the following Turkey Day was spent with a rich one. He experienced myriad walks of life: offering senior citizens either paper or plastic, hosing down trash bins for picnickers, sharing desks with overprivileged Anglos. He decided to major in sociology.

Now he lives in the melting pot of Brooklyn, N.Y., where he and Sabin share an apartment in Clinton Hill and pursue careers in social activist filmmaking. TCU may not have taught Redmon how to hold a movie camera, but it certainly channeled his interests, in and out of the classroom. He said he always wondered what sociology “looked like.”

The popularity of the bead movie is growing. Since March, mainstream theaters have booked showings. “I continuously get e-mails [from theaters],” he said. “I just don’t have the time to attend screenings or even answer all the mail.”

The 33-year-old has two more documentaries in queue. This year he and Sabin split their time between filming a post-Katrina tug at the heartstrings, Kamp Katrina, and editing Intimidad, a south-of-the-border human interest story that they have been shooting intermittently in Reynosa and Puebla, Mexico, for the past three years.

“The story is simple, but the narrative is complex,” Redmon said. “The film begins by posing the question, ‘What is intimacy for a young woman who makes intimate wear for Victoria’s Secret?’ “

“The story is simple, but the narrative is complex,” Redmon said. “The film begins by posing the question, ‘What is intimacy for a young woman who makes intimate wear for Victoria’s Secret?’ “

Ceci and Camillo are a 21-year-old couple who move to Reynosa to work in the maquiladoras (denim factories), but they must leave their 2-year-old daughter with the mother-in-law – almost 2,000 miles away. Redmon wouldn’t divulge much of the plot, only that Ceci and Camillo “struggle with many issues, including hurricanes, isolation and death.”

“We had almost complete access to their lives,” he said. He expects to sell Intimidad to a cable station and universities.

Kamp Katrina trails a kooky Ms. Pearl, one of Mardi Gras’ primary interview subjects and an avid bead collector, as she attempts to put up 14 people in her New Orleans backyard after the storm. Redmon and Sabin shared tents with the refugees from the second week of September 2005 (the first day Pearl was allowed to enter the city after Katrina) through New Year’s.

“Living in tents in New Orleans isn’t fun,” he said. “It’s dirty, noisy and unhealthy. Housing 14 people in a backyard became a tremendously stressful responsibility. The story is extremely chaotic and brutal at times, but every person’s story in the film has an arc and resolution.”

Kamp, which was finished in the fall, has been well-received at university screenings. Like Mardi Gras, Redmon plans to self-distribute.

With so many filmmakers rushing to get their hurricane horror to theaters first, Redmon was up against such avant-gardes as Spike Lee, who unintentionally landed in a Kamp reel after the Malcolm X director’s crew shoved Redmon (and his lens) out of the way for a clean shot. Apparently the footage carries on for some time.

Again, Redmon is reluctant to leave the incident in the final cut (but he may post it on his web site). He doesn’t want his sociopolitical projects to take a nasty veer and detract from the heart of the film.

With or without Spike Lee, Redmon already is discussing theatrical release with a distribution company. If that doesn’t happen, then he will self-distribute similar to Mardi Gras.

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related Reading:

Alumni, Features

CHEW to the Rescue

A desire to help dogs led Leigh Owen Sendra to launch a nonprofit veterinary clinic.

Alumni, Features

Finding a Fit

A Neeley alum matches workers on the autism spectrum to high-tech careers.