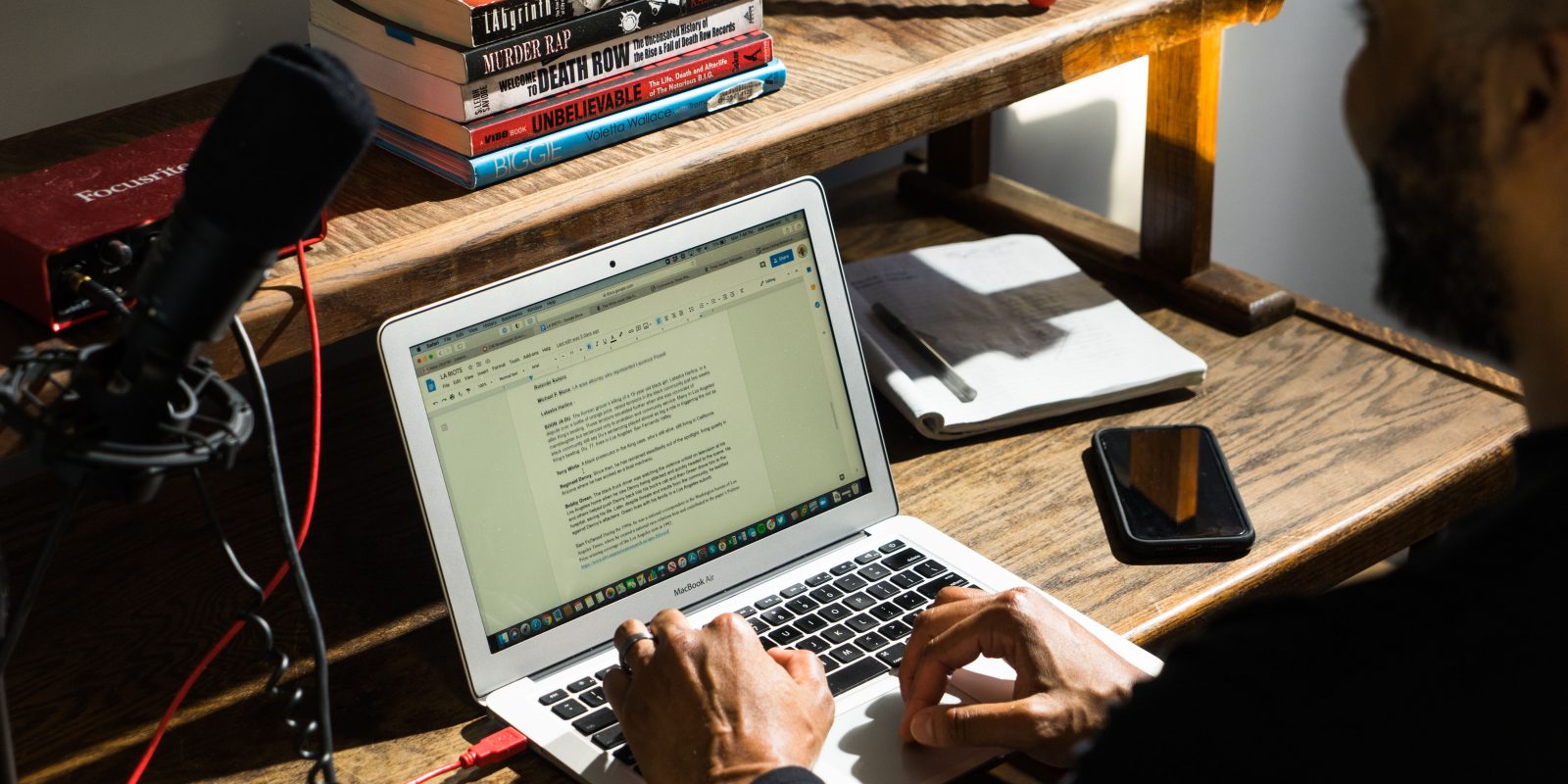

Photo by Jeffrey McWhorter

Breaking the News

News media adapts to challenges, from shrinking revenue and vanishing jobs to public distrust and a world in chaos.

Christina Ruffini ’07 covers the State Department and foreign affairs as a correspondent for CBS News. She globe-trots to places such as India and Sudan, writing articles and appearing in video broadcasts. Her job, she said, has given her some of the best moments of her life. But it’s exhausting.

“I have friends I went to high school with on Facebook telling me I’m standing in front of a green screen or making things up,” she said. “Or I’m part of a conspiracy, and I’m corrupt and I’m owned by the banks.”

Amid public mistrust, dwindling revenues, hemorrhaging jobs, forced migration to digital platforms and an ongoing failure to bring diversity to newsrooms, the first two decades of the 21st century have been a turbulent time for journalism in the United States.

In 2020, journalists faced one extraordinary situation after another. Around the nation, hundreds of journalists were attacked or arrested while documenting protests. Major news networks took the drastic step of cutting away from a live presidential address in order to fact-check claims of election fraud. All the while, reporters covered a raging pandemic, often from home and for audiences that may doubt the integrity of news organizations.

“I remember going off to college and telling people I was going to be a journalism major,” said Benton McDonald, a senior in the Bob Schieffer College of Communication who is executive editor of the student-led news outlet TCU 360. “Half the people would say, ‘Great. We need more of those.’ … The other half would [say], ‘Oh, you’re going to go work for fake news.’

“Journalism,” McDonald added, “is at such an interesting point.”

The Local Beat Takes a Beating

Newsrooms, especially those rooted in print, are in financial trouble in the digital age.

When Joel Anderson ’00 was growing up in the Houston area, collecting the newspaper from the front yard was a morning ritual. Now he’s lucky if a news website he frequents can last more than a few years.

Joel Anderson, a staff writer for Slate, said it’s difficult to keep readers’ attention. Photo by James Tensuan

“You have more of a connection to a product when you’re able to hold it in your hand, and that’s always how I felt about newspapers, just going out in the front yard and getting the paper every morning,” said Anderson, a staff writer for Slate. “Now you’re in an environment where people barely even go to the front pages of websites anymore. … It’s just much more difficult to keep readers’ attention.”

Earning their dollars is harder, too, and Anderson said economic survival is journalism’s biggest problem. The digital age has devastated the news industry’s finances. Many papers took the early and arguably catastrophic step of putting their content online for free. Having lost subscribers, they then began to bleed ad revenue.

The website Craigslist, founded in 1995, earned its founder, Craig Newmark, hundreds of millions of dollars while hollowing out newspapers’ revenue from classified ads. The industry lost billions to Google’s and Facebook’s digital ads. By mid-2012, by one measure, Google was earning more ad revenue than all U.S. newspapers and magazines combined.

Roy Eaton ’59, who co-owns the only print newspaper in Wise County, Texas, is feeling the pinch.

“The sale of advertising is our biggest challenge,” said Eaton of the Wise County Messenger, a semiweekly based in Decatur. “We just struggle to find new ways to do things to bring in revenue.”

New strategies have included special sections that highlight individual police officers, social media pages, a weekday news sheet and an ad-sponsored podcast.

Though the Messenger has remained profitable in 2020, Eaton said, “I laugh and say we saved our money during the good times.”

And, Eaton said, the paper has managed to avoid laying off anyone during the pandemic.

But nationwide, layoffs have become the norm. Between 2008 and 2019, newsrooms jettisoned almost a quarter of their workforce, with newspaper, radio, broadcast television, cable and digital-native news publishers shedding around 27,000 jobs, according to the Pew Research Center.

Newspapers drove those losses, with job numbers falling by a staggering 51 percent, or 36,000 jobs, over that period. About a thousand radio journalism jobs also vanished. (Newspaper and radio job losses were partially balanced by growth in the digital-native sector — which lumps together online publishers with libraries and web search portals — and by a small bump in broadcast jobs.)

Changes resulting in less news coverage are leaving many communities in the dark about their own goings-on.

“When I started at The Dallas Morning News in 1998, there were 650 journalists. The last I heard, there’s now 130,” said Ryan Rusak ’98, opinion editor for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. “I’m still amazed at how many people I talk to that don’t understand what’s happening in our industry. … Your local media outlets are in real trouble, and The New York Times is not going to come cover your city council.”

“When I started at The Dallas Morning News in 1998, there were 650 journalists. The last I heard, there’s now 130,” said Ryan Rusak ’98, opinion editor for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. “I’m still amazed at how many people I talk to that don’t understand what’s happening in our industry. … Your local media outlets are in real trouble, and The New York Times is not going to come cover your city council.”

Small-town papers have always been crucial watchdogs. The Messenger offers Wise County’s only coverage of school boards, city councils and county government, Eaton said. In 1990, a Texas Ranger tipped him off about a scam run by the county sheriff, for whom the paper had previously expressed support. The sheriff and two confederates had been arresting people at a roadside park and charging them with indecent behavior in order to extort money. Eaton broke the story in the Messenger, and it was soon picked up by TV stations and other newspapers.

The sheriff “called me one night at home, of course, and starts yellin’ at me. … Just before the news came on, he said, ‘Well, thank you for listening. Bye!’ and hung up.” (The sheriff, his chief deputy and a bondsman were sentenced to prison after being found guilty in federal court.)

“Rarely do we have situations like that,” Eaton said. “But if it’s not for the community newspaper calling it to people’s attention, they’re never going to know it.”

Breaking News

On Oct. 1, 2019, the city of Dallas — along with much of the nation — waited for a jury to complete deliberations in the trial of Amber Guyger, a police officer who was charged with murder in the 2018 shooting of her neighbor Botham Jean.

Rusak prepared two editorials based on the most likely outcomes. One of them went live about 20 minutes after the guilty verdict came through.

In the digital age, such reaction times are business as usual in cases like this, when, Rusak said, “the immediacy is what’s really important.”

“Is it for the better or worse? I don’t think I can answer that question because it’s a societal question,” Rusak said. The media’s relentless stream of information can be lifesaving, he said, when it involves, say, a tornado warning.

But, he added, “Do we need the stream of every bit of news, good or bad, and tragedy and horror in the world being in your pocket? That’s something I struggle with a lot, just as a person. But as a journalist, that’s what the game is now.”

Rusak also worries that the national press, at least, is growing partisan — in part thanks to algorithms that show people more of what they want to read.

“I think that the reporting is straight and fair for the most part, but what I see is a lot of national outlets framing the news in an ideological frame,” Rusak said. “If you’re dependent on digital subscribers, and digital subscribers are polarized people who want a certain point of view, your organization may trend toward giving them that point of view.”

Think Before You Tweet

As digital algorithms skew the news that reaches the average consumer, social media has freed journalists and citizens alike from the traditional gatekeepers of publishing.

But for the pros, a platform like Twitter can be a mixed blessing because it tempts them — unwisely, say TCU journalism professors — to opine.

“I have to tell my students, ‘Stop, stop, stop spouting off on Twitter on things you think you want to cover. … People are going to think you’re biased,’ ” said Jean Marie Brown ’13 MS, assistant professor of professional practice and director of student media. “But it’s hard to tell them that when people working for The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal and CNN are doing exactly what I’m telling them not to do and still covering things.”

Patty Zamarripa, assistant professor of professional practice, right, mentors future journalists like Corinne Hildebrandt ’19, now a news producer at KTVX in Salt Lake City. Zamarripa tells her students to avoid expressing opinions publicly. Photo by Jeffrey McWhorter

In early 2020, a group of TCU journalism students grew furious about allegations of racism on campus and wanted to protest. Patty Zamarripa ’10, assistant professor of professional practice, saw the emotions as a teaching moment.

“ ‘This is not your opportunity to air your grievances,’ ” she told them. “ ‘You don’t get to have an opinion.’ ”

“People are not as media-literate as they think they are,” Zamarripa said. “It’s incredibly important that we don’t put our opinion and that we write and report in an unbiased way so that people can make the best decision for themselves.

“Young people feel that they can change the world with writing a blog, or writing a tweet, or giving their opinion, and I’m glad that they feel that way,” she said. “But when you decide to become a journalist, some of those freedoms kind of have to go away.”

To McDonald, the way Twitter allows journalists to amplify their opinions and cultivate a public personality isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

“If I follow someone on Twitter, and I enjoy their tweets … [and] if I agree with their views more,” he said, “then I’m definitely going to be more inclined to read them and see their reporting.”

Still, for his part, McDonald said that when he feels tempted to fire off an opinion on Twitter, “In the back of my head, I’ve said, you know, is this smart? How is this going to look to someone that reads your next piece? Most of the time, I’ll end up deleting and not tweeting.”

The Gatekeepers Are Gone

Meanwhile, although anyone can speak on social media, not everyone’s voice is amplified — so only some are heard, said Melita Garza, associate professor of journalism.

Melita Garza, associate professor of journalism, said without trained journalists as gatekeepers, bad ideas don’t necessarily just get dismissed. Photo by Jeffrey McWhorter

“There’s so many voices out there,” she said, “the chances of yours being heard over some others aren’t necessarily that great.”

That cacophony, and the way it can enable falsehoods, may dispel the hopeful notion that we live in a “marketplace of ideas.”

The phrase optimistically implies a world in which, as Garza put it, “reason and common sense would lead to the triumph of the truth, and those wacko ideas would just sort of fade away because people would dismiss them using their own good judgment.”

But in a social media arena lacking gatekeepers and rife with misinformation campaigns, bad ideas don’t necessarily just get dismissed. To illustrate, Garza pointed out that the false belief that Hillary Clinton was involved in child sex trafficking led one man to fire shots in a Washington, D.C., pizza shop in December 2016.

The rise of the citizen journalist means anyone can now write something and reach many people, said Uche Onyebadi, associate professor and chair of the journalism department.

“The legacy media are no longer in absolute control,” he said. “But then therein lies another pitfall, in the sense that most of the time, you can’t trust what you’re reading. … Was it vetted? Did you interview somebody? Did you look at all sides of the story? Were you very ethical? How about accuracy?”

“The more outrageous and viral you can make whatever your message is, is often what propels it to more readers and viewers,” Garza said. “Not necessarily that there’s any truth in it.”

Data-Driven

Digitization, of course, comes with upsides, especially in the pandemic era. The ability to meet with co-workers virtually and publish entirely online allowed newsrooms to continue covering the news as Covid-19 forced people to work from home — a change that didn’t faze digital natives such as McDonald and his fellow students.

“We’re already so used to being online and used to communicating not in person that I don’t think it was probably as hard of a transition” compared to other newsrooms that were forced to shut down when the virus struck, McDonald said. Working virtually on TCU 360, he said, is “second nature to us.”

“We’re already so used to being online and used to communicating not in person that I don’t think it was probably as hard of a transition” compared to other newsrooms that were forced to shut down when the virus struck, McDonald said. Working virtually on TCU 360, he said, is “second nature to us.”

And while the pandemic has limited the ability of political and sports journalists to conduct shoe-leather reporting, it has presented a vast open field for reporters such as Jordan Rubio ’14, a data journalist with the Houston Chronicle.

As cases began to spread in Texas, Rubio devised a way to track coronavirus rates by county. In the process, he and his team uncovered tens of thousands of cases health authorities were missing.

“Data has become a source like any other in 21st-century journalism, and you need people who can … understand that source and be able to interview it,” Rubio said.

Sharing data-analysis methods publicly, Rubio added, is just as important. Ethical reporting demands that journalists disclose where their data came from, how they crunched that data and why they analyzed everything the way they did.

“The digital age affords journalism a greater opportunity to be more transparent than ever before,” Rubio said, “to show people how the sausage is being made.”

Still, amid layoffs, Rubio said, transparency can be difficult. “There’s definitely an opportunity to explain to people how we work, but we don’t have the requisite staffing to do so. … There’s not enough journalists.”

The Sun Still Sets in the West

Transparency is all the more crucial amid growing public mistrust of news media. The reasons for that mistrust are complex, but they go beyond partisanship to include the decline of local coverage, the juxtaposition of opinion pieces with straight news, and the broader difficulty of spotting truly reliable information amid the online sea.

Jean Marie Brown, assistant professor of professional practice and director of student media, instructs students like Kate Redfield ’20 to be mindful about how they use their personal social media and how they represent themselves. Photo by Jeffrey McWhorter

For their part, journalists have long been “playing with false equivalence,” Brown said.

“Barack Obama was born in the United States. To say, ‘Well, some people say he wasn’t, so we have to make that a story’ — in many ways, they legitimize the falsehood,” Brown said. “It creates a climate that says, ‘Everything is up for debate.’ But at the end of the day, the sun sets in the west.”

McDonald has also been unnerved by what he calls the media’s overused commitment to showing “both sides,” he said. “I don’t really think the ‘both sides’ holds up when one side isn’t using facts.”

Amid attempts on digital media to promote misinformation, Rusak said, readers need a referee to point out what’s true and what isn’t.

But who that is, or should be, is not clear. As Onyebadi put it, “There are no more Cronkites.”

It doesn’t help that many people whom the public perceives to be journalists actually aren’t embodying the role, several people said.

“Rachel Maddow, Chris Cuomo, Tucker Carlson — those people aren’t journalists in the sense that they are going out and trying to report something and present something unbiased. They are commentators,” Brown said. “But the public can’t figure out the difference.”

“As soon as you outwardly pick a side in an issue that you’re trying to cover objectively, you lose all credibility. … I see a lot of unforced errors with [journalists] volunteering that information,” Ruffini said. “More and more people are confusing advocacy with journalism.”

Fair and Balanced?

The ideal of true journalistic objectivity may always have been a mirage, based in part on the profession’s ongoing lack of newsroom diversity.

Compared with other groups of workers in the U.S., newsrooms remain disproportionately white and male. Forty-eight percent of journalists, in fact, are white men, compared with 34 percent of workers overall, Pew reports. Despite proclamations of a commitment to diversity, many newsrooms seem not to be taking that commitment seriously. In 2018, for example, most did not even respond to the American Society of News Editors’ annual newsroom diversity survey.

“It would seem that the digital age would allow for greater access, which would seem to imply greater democracy,” Garza said. “But none of that can be fully realized without a greater emphasis on hiring, recruiting and promoting people of color.”

![A newspaper tear that includes print around the edges to look like it was ripped straight from the headlines. Superimposed on top are the words “The way we’ve been socialized to think about others across these broad fault lines [is] one impediment to this rosy idea of being bias-free.” — Melita Garza](https://magazine.tcu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Garza-Quote-171x500.jpg) Too often, Garza said, journalism still speaks to a white-majority perspective. But to seek truth in reporting, she said, means to tell the story of the diversity and magnitude of the human experience and to seek sources whose voices are seldom heard.

Too often, Garza said, journalism still speaks to a white-majority perspective. But to seek truth in reporting, she said, means to tell the story of the diversity and magnitude of the human experience and to seek sources whose voices are seldom heard.

“If your newsroom isn’t doing that,” Garza said, “then your newsroom is not operating in an ethical manner.”

Every journalist — indeed, every human being — has “fault lines,” or sources of personal bias that arise from their own gender, sexual orientation, generation, geography, race and class. So taught Robert C. Maynard, a journalist who worked to desegregate the nation’s newsrooms and who founded an eponymous institute for journalism education. His ideas inform Garza’s and Brown’s teaching.

“The way we’ve been socialized to think about others across these broad fault lines [is] one impediment to this rosy idea of being bias-free,” Garza said.

Brown remembers an encounter with white journalists’ fault lines while working in a newsroom as it reported on a fire. The calamity had killed a grandfather and one of his grandchildren, and her colleagues perceived there was something wrong with the fact that they’d been together.

“The newsroom went on this whole tangent about, ‘Why were those children with their grandparents? … Where were their parents?’ ” Brown said.

The parents, it turned out, had been working and looking for housing. By contrast, in that newsroom, new mothers normally stayed home to care for their children.

“That always stayed with me,” Brown said, “because it was a case of the class norms of the newsroom coloring the way they look at what really was a norm, which is children being with grandparents.”

A diverse newsroom can help correct these fault lines, Brown said, by illustrating truth and including crucial context.

For instance, Rubio said, in writing about a poor community with low-performing schools, journalists must mention relevant history, such as a legacy of disinvestment, lest the people living in that community come off looking pathological.

“Without looking at how, over the years, decisions were made that adversely affected this community, we’re not telling the whole truth,” Rubio said. “It’s substantially untrue while being factually accurate.”

In fact, there is no such thing as objectivity, Brown said. “You need to be aware of your bias. And you need to understand how your bias influences you so you can correct that.”

There is, then, a humility central to good journalism. Garza referred to “that recognition that you don’t know everything and that you need to fill in those gaps. … We’re supposed to be curious. We’re journalists, right?”

Unpopularity Contest

Growing public mistrust and a pandemic add to the challenges of Christina Ruffini’s job covering the State Department for CBS News. Courtesy of Christina Ruffini

When Covid-19 hit, as TCU journalism students scattered to report on the pandemic from their homes in Hawaii or Nevada, Ruffini scrambled to master the technical aspects of broadcasting from her apartment, from digital hardware to lighting to makeup. Professional networking — the in-person kind D.C. beat reporters rely on to develop sources — became much harder. And getting international visas, once a quick task, became a days-long ordeal.

But Ruffini’s job had grown more onerous long before Covid. The once-staid State Department had become hyperpartisan and was no longer isolated from political rancor, she said. And covering issues in depth has become harder amid all the noise of nonstop political news.

“It’s deafening, and it’s drowning out some really important stories and some really important issues,” she said. “Unfortunately, those stories and those issues, they’re not what people are clicking on.”

Ruffini said some moments felt downright surreal. Once, she read a White House official a series of seemingly contradictory statements he had made about the origins of Covid-19 and asked him to clarify his position. “He just looked at me and said [something like], ‘Well, both things can be true. What don’t you understand about grammar?’

“There’s a screen grab of me just kind of staring at him with my mouth open,” Ruffini said. “You just feel like the ground is constantly shifting underneath you. … It feels very Kafkaesque.”

Ruffini suspects many dedicated journalists will quit the profession from sheer exhaustion.

“You just wonder why you’re sacrificing so much … to do something you believe in,” she said, “when no one else seems to believe in it anymore.”

The Good News

Not all news about the news is bad. Between 2008 and 2019, cable television and broadcast news job numbers remained stable, according to Pew, while jobs at digital-native news outlets more than doubled from 7,400 to about 16,100. And at least one legacy paper is thriving online. In August 2020, The New York Times announced that digital revenue, including ads, had exceeded print revenue for the first time. Three months later, its earnings from digital subscriptions had topped those from print subscriptions — another first.

Still, as the pandemic further accelerates ad revenue declines, whether small, modestly resourced print newspapers like the Messenger can stay afloat or grow is unclear.

Still, as the pandemic further accelerates ad revenue declines, whether small, modestly resourced print newspapers like the Messenger can stay afloat or grow is unclear.

“The major factories, at least in the automotive industry, are telling everybody, ‘You know, the future is in online [advertising],’ ” Eaton said. “They may be right. I don’t know. But we’re going to hang in there.”

In spite of everything, some faculty members are inclined to be sanguine about journalism’s future. The profession has supposedly been doomed since the 1950s, Brown said. That’s when television began cutting into daily papers’ profits and shutdowns began.

She predicts a rise in nonprofit and smaller-scale outlets.

“Just because the business model changed doesn’t mean journalism is going to die,” she said. “I generally tell students that I think that if they want a job, they’ll get a job. … Learning how to accurately collect information and distill that information to the public in a manageable way — that skill set is golden. And I think it will always be golden.”

The ability to adapt will remain key, too, Onyebadi said.

“It’s a natural evolution because technology is changing, and it will continue to change,” he said. “Journalism is very dynamic — that’s one of the things I like about it. You need to be a journalist who catches the train as it moves, not when it has already left the station.”

Your comments are welcome

1 Comment

I am a retired reporter and editor (print) and am concerned about what the media is going through. This is one of the best pieces I have read on this topic! Well-written, great sources and fact-driven. Jenny Blair is a pro. I predict great things for her.

Related reading:

Features, Research + Discovery

Collin Yoxall’s Research Helps Advertisers Account for Social Media Fatigue

Platforms enable two-way conversations between brands and consumers, but users may be ignoring advertisements in their feeds.

Campus News: Alma Matters

Faculty Roundtable: Journalistic Inquiries

If you were a journalist, what would your beat be and why?

Alumni

Skip Hollandsworth’s Texas Tales: From Closets to Crime

Skip Hollandsworth, in his nearly 30 years of writing, has chronicled the best and worst of the Lone Star State.