Photo by Joyce Marshall

Tracing Colonial Mexico with Maps and Ink

Alex Hidalgo re-creates the colonial experience in Latin America with mapmaking, astronomy and a scriptorium by candlelight.

Indigenous maps of colonial Mexico in the 16th to 18th centuries — and the materials used to create them — have captured Alex Hidalgo’s imagination for nearly a decade.

“In my research, I examine maps made by Indian painters, documenting land exchanges, conflicts, infrastructure development and so forth,” said Hidalgo, associate professor of history and director of undergraduate studies. “I would see different types of ink on these maps, and I wondered how they were made and what kind of materials and knowledge went into making a map from scratch.”

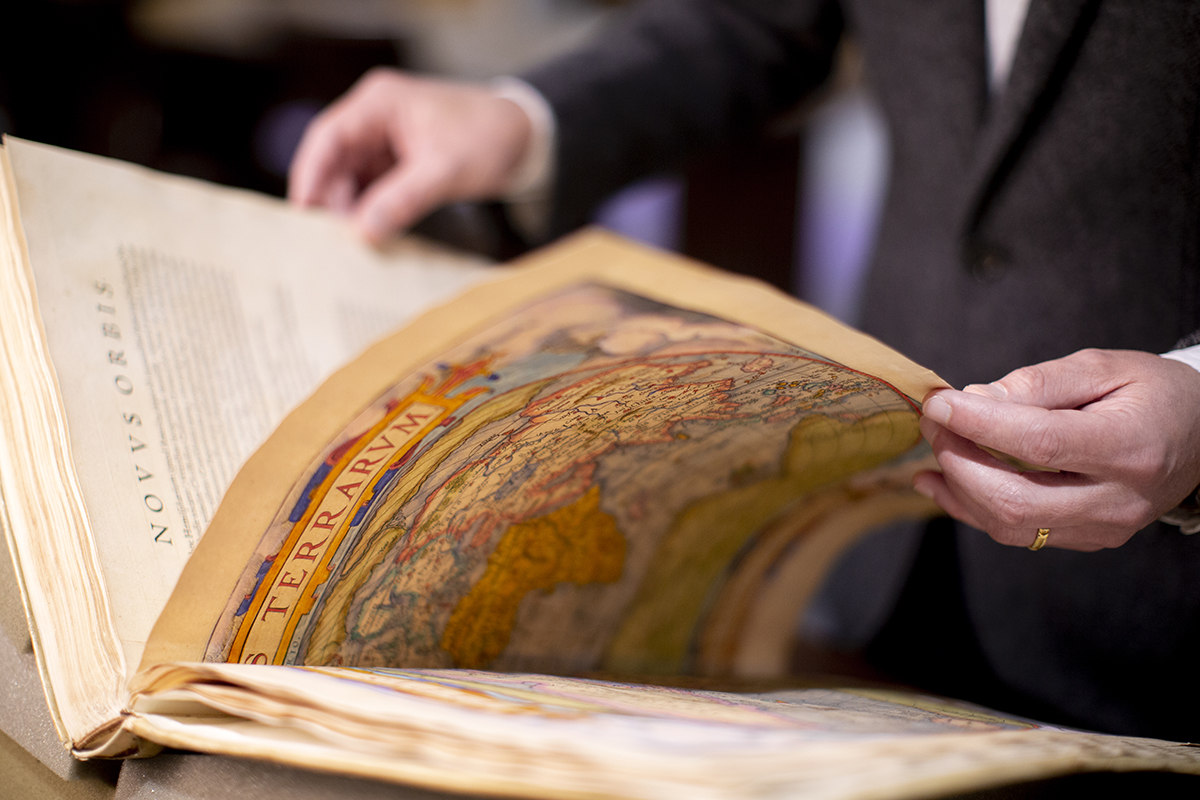

Alex Hidalgo, associate professor of history and director of undergraduate studies, reviews old maps in his favorite place on campus, the Special Collections reading room on the third floor of the Mary Couts Burnett Library. Photo by Joyce Marshall

The word map may conjure images of tattered, impossibly folded pages stuffed in glove boxes in pre-internet America. But Hidalgo said the maps he studies are more like indigenous paintings “that incorporate pre-Columbian motifs and symbols and, later, European-style landscapes or Christian churches.”

“There are a couple of layers: There is the map itself, how the painter delineates all the geographical aspects, and since these aren’t just works of art — they have a utility — you see a layer of the map where Spanish officials have come along and made annotations,” Hidalgo said. “These annotations seem to be both part of the maps and outside them.”

European Influence on Mexico

The maps testify to colonial encounters marked by privilege and exclusion, Hidalgo said. Though visually stunning, the maps veil “the fact that they functioned as tools of empire designed to redistribute land according to Spanish priorities.”

Hidalgo explores this hegemonic interplay in greater detail in Trail of Footprints: A History of Indigenous Maps From Viceregal Mexico (University of Texas Press, 2019).

His interest in these maps expanded into attempts to replicate the process used to create them. The Spanish introduced iron gall ink to the Americas, prizing their formula over native inks for its luster and richness. But centuries-old ink formulas aren’t easy to come by. Hidalgo spent several years piecing together recipes from lists of ingredients found buried in archives throughout Europe, scattered among a variety of primary sources and often jotted down in margins.

Iron gall ink “has a very specific composition that includes three different ingredients: acid from tree galls, iron sulfate and a binder called gum arabic,” Hidalgo said. “When you mix them together, you get this rich, black ink that has this acidic quality that burns through paper over time.”

In his graduate course Nature and Society in the Iberian World, Hidalgo wanted students to witness and, when possible, experience the ways in which ancient people developed and passed down a craft by working with natural elements and transforming them into tools for everyday use.

“We don’t think about things like that now,” he said. “If we want to write, we buy paper, we grab a pen. There are hundreds of different pens of all colors at the drugstore.”

Recreating Iron Gall Ink

To test the iron gall ink recipe that he mined, Hidalgo recruited Kayla Green, associate professor of chemistry.

“It was exciting to envision the use of chemistry to help teach such a historically significant lesson.”

Kayla Green, associate professor of chemistry

“It was exciting to envision the use of chemistry to help teach such a historically significant lesson,” Green said. “As anyone who has taken one of my chemistry courses will tell you, I have a personal interest in history and the individual stories of the characters involved.”

Under Green’s guidance and with the aid of modern glassware, stirring rods and liquid reagents, Hidalgo and his students attempted to re-create iron gall ink — the same kind used to pen the Declaration of Independence. Green concocted a batch ahead of time, and it looked authentic. Still, Sarah Miller ’19 MA said she harbored some doubt.

“I didn’t think it was going to work,” said Miller, who had confidence in her skills as a historian but was in less familiar territory in the chemistry lab.

In fact, Miller and her classmates were unable to replicate the viscosity typical of iron gall inks in the 16th to 18th centuries. Instead, they produced something thinner, more like watercolor.

Scriptorium by Candlelight

Since that first iron gall ink experiment, Hidalgo has added a component to the syllabus called the scriptorium by candlelight, which simulates the 17th- and 18th-century writing process. He learned of this exercise through the Andrew W. Mellon Society of Fellows in Critical Bibliography, a fellowship he received in 2019 that aims to advance the study of rare books as material objects.

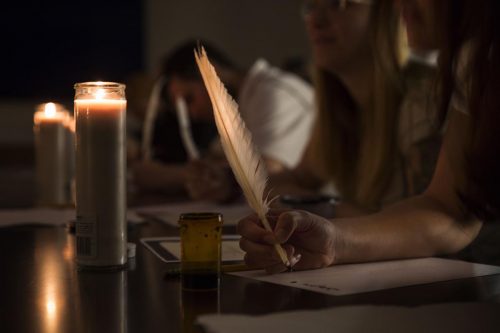

During an exercise called scriptorium by candlelight, Alex Hidalgo’s students copy Spanish manuscripts using handmade iron gall ink and quills. Courtesy of Alex Hidalgo | Photo by Scott Murdock

“I turn out the lights, and I have my students copy by candlelight samples of colonial Spanish manuscripts using rag paper — the type used in the early modern era — and the iron gall ink and the handmade quills they made during the lab.”

Hidalgo said the hands-on nature of the ink experiment and follow-up scriptorium underscore how knowledge of craft works.

“It takes practice and experimentation, and it’s passed down through generations,” he said. “Also, [the experiment] illustrated how new knowledge and understanding comes by transdisciplinary research — combining efforts across disciplines.”

Hidalgo is designing an undergraduate course that will incorporate astronomy into the study of Latin American history. The class will include a trip or two to an observatory, he said.

“In our readings, we look at how people used the stars for various purposes like mapping, determining weather patterns and even explaining human behavior,” Hidalgo said. “I’m hoping that by collaborating with an astronomer, we can learn about how the different alignments of stars have been understood across time and how modern-day astronomers understand it all within their discipline. I’m really just trying to make Latin American history come alive.”

Your comments are welcome

1 Comment

That sounds like an amazing class!

Related reading:

Research + Discovery

Ancient Manuscript Describes Assimilation of Aztecs

Art historian Lori Boornazian Diel decodes the story of Spanish invasion and the struggle to find a new identity after defeat.

Features

Adam Fung’s Uncommon Arctic Adventure

The art professor is acting as an Arctic ambassador and filmmaker after his 19-day residency in the Far North.

Features

Bill Morse Helps Cambodians Remove Landmines

After decades of war, alumnus works to clear the field and build schools.