Comics in the Classroom Spark Creative Thinking

The medium itself breaks boundaries, and this idea transfers to course subject matter.

Comics in the Classroom Spark Creative Thinking

The medium itself breaks boundaries, and this idea transfers to course subject matter.

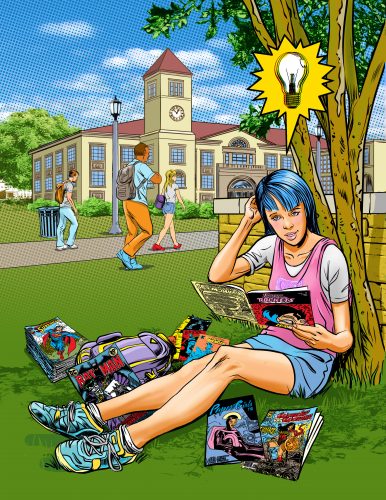

A list of required reading can spark interest for students or, sometimes, apathy. Add comics to the syllabus and suddenly students are intrigued.

Illustration by Miracle Studios

“That’s the thing about comics: We lure students in,” said Wesley Cray, assistant professor of philosophy. “They think it’s going to be fun, which it is, and they think it’s going to be easy, which it’s not.”

Faculty members leverage comics in their courses for various reasons, including as a catalyst for conversation and critical thinking and a way to grapple with thorny concepts. The very nature of comics conflicts with notions of what classroom learning is about.

“Comics can interrupt and open up our perceptions. We expect, in a class, to be reading a text. But then you’re given a comic,” said Dave Aftandilian, associate professor of anthropology. “It’s breaking you out of that expected box and helping you think in new ways.”

Comics sales topped $1 billion in 2018 in the United States and Canada, as they did in the three years prior, reported Comichron, the online repository of comics circulation data.

TCU students purchased some of those comics for class reading.

“We talk about literacy in comics,” Cray said. “Comics are often thought to be a dumbed-down form of reading. But it’s actually a very, very advanced form of literacy because you’re having to read text and image in conjunction and track spatial and temporal progression on a page. It’s really kind of sophisticated.”

Comics panels without speech or thought bubbles force readers to be analytical. “We put a lot of stock in literacy with respect to words,” said Cray, who teaches the Philosophy and Comics course.

“We kind of put aside visual literacy and competency and the ability to read things as text when they don’t have letters in them — read people or read situations,” he said. “Comics force you to juxtapose text and image to create a language that’s not easily codified.”

Jason Helms, associate professor of English, said panels without text, those that focus on a character’s emotions through facial expression, have to be read in a way different from a novel.

“Those angry stink lines above their heads are actually a verbal element, not just a visual,” said Helms, who teaches Seminar in Rhetoric: Popular Culture and New Media as well as Visual Rhetoric, Graphic Novels and Comics. “We understand what they mean.”

Examples: A light bulb means an idea; stars circling mean pain. “One of the cool things comics does is that it often inverts things,” Helms said. “Things that are visual get read, like we would text; things that are verbal, like words, actually get seen.”

“The meaning of a comic doesn’t happen in the punchline. It happens between the panels.”

Jason Helms

Reading long-form comics is an adjustment for some students whose only exposure might have been Peanuts or Garfield in newspapers. They expect to be led to a witty payoff. “The meaning of a comic doesn’t happen in the punchline,” Helms said. “It happens between the panels.

“Similarly, the meaning of life you often don’t find in the punchline. You don’t find it on that Saturday night when you go out with friends.” Significance is often found in more mundane pursuits. “Sometimes when you’re walking from one thing to the next. Set up your life so you can have those meaningful moments. You matter. Your life matters.”

Often, people who couldn’t read the news in newspapers would turn to the comics pages. Comics have been seen as a medium for the semi-literate, Helms said.

The popularity of comics is undeniable, but their place in academia has been controversial. In November 2018, three Washington and Lee University alumni sent a mass email bashing a list of 20 courses. The document, “The ‘Dumbing Down’ of the Curriculum at W&L,” listed two creative writing and studio arts hybrid courses on creating comics. The missive said they have “dubious academic value, dedicated to the espousal of a political agenda, trivial, inane, or some combination of the above,” and called for the elimination of the courses and their professors.

“I think just the timbre of the complaint is really interesting — that it represents a dumbing down of the curriculum,” Cray said. “Even if we grant that comics are juvenile, it doesn’t mean serious study of them needs to be juvenile. But we don’t even grant that they’re juvenile.”

To challenge the categorization of “high art” and “low art,” Tricia Jenkins asks her Media Adaptations students: What is the difference between an opera and a rock concert?

“They’re both music. They’re both public performances,” said Jenkins, associate professor of film, television and digital media. “But opera is considered high art, and a rock concert is considered low art.” Why?

“The divide between high art and low art is sort of class-based,” Jenkins said. “In general, high art like poetry or painting or sculpture has that bourgeoisie connotation because either you need a special education in order to be able to understand it, or you need money to participate in it, or it also demands a physical restraint.”

Operas, for example, are not typically performed in English, so training in another language such as Italian is necessary to understand them, she said. Audience behavior is also a factor.

“At an opera concert, you’re really just expected to — at the most — clap enthusiastically. But at a rock concert, you might be in a mosh pit or getting drunk and headbanging,” she said. “The potential for unruliness is much higher in popular art. So things that are popular tend to be dismissed as not great art. But I think they can be.”

Class-based distinctions guided art critics in the past, but Jenkins said her course takes a postmodern view on art and challenges those ideas.

Art is everywhere, and the possibilities for creative expression are endless, Jenkins said. “Andy Warhol made the argument that advertisement is art — that’s why he painted the Campbell’s Soup can. When you go to the supermarket, it’s full of art. You just don’t see it that way because you’ve been trained not to see advertisement and packaging as a form of art, but a graphic artist designed that packaging.”

Illustration by Miracle Studios

A Sign of the Times

The quick production of comics gives the medium a distinct characteristic. “More than nearly any other art form, they immediately reflect their culture of creation,” Cray said. “You can go from idea to on the shelf in three to four months. No other mass-produced art form can be produced that quickly or cheaply.

“When you read [comics] critically, you learn not just what the author was doing and the story they were telling, but you learn very much about the very particular time of creation.”

Wesley Cray

“If you want to see what is representing the newspaper reality of the moment, comics is where it’s at. When you read them critically, you learn not just what the author was doing and the story they were telling, but you learn very much about the very particular time of creation.”

The cultural function of a comic, Helms said, “has shifted radically over time.” In the golden age of comics, they had moralistic themes and rallied Americans during World War II. Modern comics are more complex in character and storyline. They can be grim or explore dystopian near-futures, as with Watchmen and V for Vendetta.

But even a century ago, comics were testing their limits, balancing what was safe with expression.

The comic strip Krazy Kat, for example, ran in newspapers from 1913 to 1944. In it, cartoonist George Herriman subtly challenged several societal conventions. The feline’s gender was ambiguous, and Herriman, a mixed-race man who passed as white, explored race in his comic, Helms said.

Title character Krazy Kat, a black feline, loved Ignatz, a white mouse, but his love was unrequited. That infatuation was interrupted when Ignatz got covered in coal dust. Krazy wasn’t interested in a black mouse. To further underscore attraction based on color, Herriman wrote about the black feline going to a beauty parlor to be dyed white. Ignatz was suddenly smitten.

“Times change and expectations change,” Jenkins said, using the movie Wonder Woman as an example. “In a lot of ways, you don’t want to stay true to the gender ideals from the 1940s. The filmmakers didn’t stick to the 1940s formula, and I think if they did, they would have been eaten alive.”

But Wonder Woman has endured like other superheroes. Those characters are steadfast for a reason. “I think in a lot of ways comic book characters are ideals,” Jenkins said. “Captain America is a great example of somebody we might wish that more people would be like in terms of being self-sacrificing and strong.”

At the same time, Jenkins said, readers are attracted to the humanity of characters, including their failures. “Iron Man drinks too much. Thor has family issues and daddy issues. He’s a god, but it’s really about his human problems.”

Character growth is an essential component to comics and all literature, but Cray said it can provide more. Engaging with fiction helps with the development of empathy. “If we want to break down barriers and have people really talk across differences, having them engage in as much fiction that gets them outside of their own head as much as possible is an important component to that.”

Breaking Out of Boxes

Comics can be cathartic for the writer and the reader. Aftandilian’s course Native American Religions and Ecology comes with a trigger warning.

Native women are abused at much higher rates than in other U.S. populations — abuse often not reported and often perpetrated by non-Natives against those women, reports the Department of Justice.

The title character of Deer Woman: An Anthology, a comic book Aftandilian uses in his class, helps return agency to victims. Deer Woman punishes abusers. All comics in the anthology were written by Native people, and they cover contemporary issues including resistance and assimilation.

“On the one hand, using the medium of comics, you might think of that as assimilation because that’s kind of a white-people thing,” Aftandilian said. “It’s also a way to get to young people, young Native people, and to share with people outside of the culture in a way that’s easier to understand than text.”

As for animals, which cannot tell their stories in a way that humans would understand, there are more comics to explore. Aftandilian, also director of the human-animal relationships minor, and Nick Bontrager, associate professor of art, co-teach Into the Small: Little Animals in Art, Culture and Museums.

Part of the class is dedicated to making art from the perspective of animals. Aftandilian gave students theoretical background on the personhood of animals, so they could be seen as thinking subjects with emotions similar to those of humans. Mouse Guard by David Petersen and Squarriors by Ash Maczko and Ashley Witter were required reading for the course.

In Mouse Guard, each mouse has a different-colored cape and fur to distinguish it, and each has a different personality. In Squarriors, the world is devoid of humans. Animals form societies with clashing ideals, and war breaks out.

“I see it as a form of storytelling sitting in between art and literature and sort of taking on bits from each of those and putting them together.”

Dave Aftandilian

Aftandilian also uses comics in Animals, Religion and Culture. We3 by Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely introduces students to intersubjectivity. Animals from different species work together and become something greater. We3 is about a dog, cat and rabbit that are genetically modified and trained to be a fighting unit.

To convey ideas or concepts relevant to his courses through comics, Aftandilian relies on the storytelling aspect to start breaking boundaries. “It’s using images to tell a story. It’s using images to capture attention.

“It’s using images to help us see things in the world in a new way,” he said. “I see it as a form of storytelling sitting in between art and literature and sort of taking on bits from each of those and putting them together.”

Animals that cross boundaries trouble us, Aftandilian said. Liminal animals have special powers and are dangerous because of those powers. The Cherokee talk about an animal called the uktena, which is part snake with wings and deer antlers.

“The animals that bust out of our little category boxes are particularly troubling — or interesting,” Aftandilian said.

Comics do the same thing.

Aftandilian said he hopes seeing things for more than one aspect of their identity — more than a book, more than a picture, more than a crawling land creature — helps humans recognize their own complexities.

What is a larger struggle, Aftandilian said, is breaking through the “othering” that starts in childhood. Animals become others and then lesser. “That same othering and denigration that begins with animals ramifies into all these other binaries, all of them looking at one side of the equation as less than the other, even though it’s patently ridiculous.

“But it’s so ingrained in us to do this categorizing, to put things in their boxes, and unfortunately it often means an ordering — a hierarchy,” Aftandilian said. “The othering of animals leads us to ‘other’ all kinds of beings — human beings — and almost always in ways that are bad for everybody.”

Comics present a sense of cohesion.

“It’s putting art and literature together to tell a story in a new way to help us think about it, I hope, at a deeper level,” Aftandilian said. “That’s really what I like about comics and using them in class: It’s harnessing that power of art to capture our imagination and our attention. It gets us to see things very differently.”

Your comments are welcome

1 Comment

Just as a point of interest, I have physical reading issues, namely intractable migraines, and I’ve switched almost exclusively to audio. I have to have someone else usually read articles like this one to me because it will trigger a cluster headache or nausea or both if I try. However, I learned some 4 years into being disabled that I could read comic books. Period. I cannot read more than a page of a physical book or ebook without getting sick (no matter the lighting level), but I can read comic books for hours. I can feel the difference in the connection and I would love to see even more studies done on the way comic books make their commute through our skulls. Very happy to see this direction from my alma mater. –Katherine R. (’05)

Related reading:

Alumni, Features

Through Comics and Video Games, Molly Mahan Tells Stories

The senior narrative editor for Riot Games previously worked for DC Comics and Dynamite Comics.

Features, Research + Discovery

When Scripture and Superheroes Collide

Johnny Miles says modern superheroes and ancient Jews have a lot in common.

Alumni, Features

Duane Bidwell and the Complexity of an Interreligious World

Through his teaching and writing, the professor at Claremont School of Theology affirms the fluidity of religion.