TCU Educates the Next Generation of Rwandan Leaders

Rwandan students seeking ways to positively impact their country’s future turn to TCU.

Thousands gather in Kigali, Rwanda, in 2014 to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the country’s genocide that left nearly 1 million people dead. Women are a major part of the effort to rebuild Rwanda and some of the next generation of leaders are studying at TCU. Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

TCU Educates the Next Generation of Rwandan Leaders

Rwandan students seeking ways to positively impact their country’s future turn to TCU.

During the 1994 Rwandan genocide, soldiers and militias killed nearly a million people and raped between 250,000 and 500,000 women. As the country recovered, women took on new roles in their communities, in the economy and in the government. But it wasn’t only because there weren’t enough men left to lead.

“Rwanda is an example of how the tragic upheaval of war can create disruption of a society, allowing for an unexpected breakthrough for women,” Swanee Hunt ’72 wrote in her 2017 book, Rwandan Women Rising (Duke University Press).

New constitutional quotas mandated that women hold 30 percent of all elected and appointed government positions. In the 2003 election, the first since the genocide, women won almost half of the seats in Rwanda’s lower house of Parliament. Today, women hold 64 percent of the seats in the lower house, along with half of the positions in the Cabinet and Supreme Court.

Social changes unfolded in tandem with women’s political gains. New laws allowed women to inherit property and criminalized domestic violence. Women took on professional roles previously held by men. They spoke out and took leadership positions in their communities, no longer content to wield influence through their husbands.

“There wasn’t a road map for these women,” Hunt said. “No one told these women how to do it. They just decided to do it.”

Rwandan Women Rising captures the voices of 90 women who transformed their country. Rwandan women studying at TCU may be among the next leaders to join them.

In recent years, the Carl and Teresa Wilkens Award and Bridge2Rwanda have brought more Rwandan students to campus. Three women who began their studies in TCU’s Intensive English Program are deciding how best to make an impact when they return home.

Yvonne Mukamudenge Umugwaneza ’17 suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder after the genocide, in which she was injured in a bomb blast and more than a dozen of her relatives were killed. In April 2014, she attended a commemoration of the 20th anniversary of the genocide in Washington, D.C., and spoke about her experience during TCU’s commemoration on campus.

Inspired by her country’s shift to criminalize violence against women, Umugwaneza, 39, is considering going into criminal justice. Before the genocide, she said, a husband could abuse his wife, and even if the neighbors knew, no one would try to stop it. It was taboo for a woman to say she had been sexually abused. “She would take it to her grave, because it was only going to be a shame for her and her family,” Umugwaneza said.

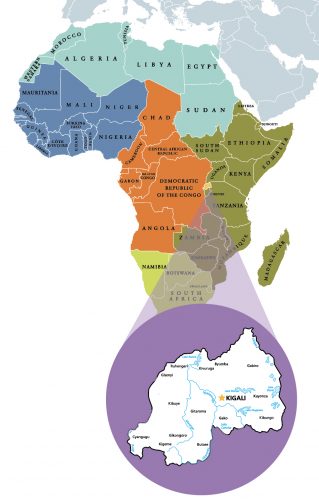

Illustration by Getty images © PeterHermesFurian

During the genocide, rape was used as a weapon of war. Afterward, for the first time in history, it was prosecuted as a war crime. The taboo on reporting rape is no longer as strong, Umugwaneza said. “People are opening up to speak about, and speak against, these things, because the government has taken a stance.”

The World Economic Forum named Larissa Uwase one of Africa’s top five women innovators in 2016, an honor that came with an invitation to attend the forum’s discussion on Africa in Kigali, Rwanda. At the event, she talked to other women who, like herself, had started small businesses with very few resources.

Uwase’s enterprise, which she co-founded during her freshman year of college, is partly a response to the food shortages she saw as a child. Uwase and her colleagues are working with smallholder farmers, primarily women, in the southern provinces. CARL Group makes products such as bread, spaghetti and doughnuts from orange-fleshed sweet potatoes, a variety that is somewhat new to Rwanda. The vegetable offers more vitamin A than the white-fleshed sweet potatoes traditionally grown in the East African country.

Uwase, 25, didn’t experience the genocide herself, but she witnessed its effects on those who did. “Growing up in an environment where some people are really hopeless was something that affected me but also other children in my age,” she said. “But it was also something that gave us courage and determination to make a change in our community.”

Claudine Mukanyamwasa ’18 MSW lost more than a dozen relatives in the genocide. As a 10-year-old, she fled to neighboring Burundi and spent three months in a refugee camp. She later earned her undergraduate degree in Rwanda and taught high school before coming to TCU to study English. Mukanyamwasa, 34, completed a master’s degree in social work, which she may use to work in the mental health field or with youth in detention centers.

The National Unity and Reconciliation Commission encouraged a climate of forgiveness to help the country survive. Mukanyamwasa said that climate, along with church teachings, helped her forgive the people who killed her family — though she emphasized that every survivor walks a different path. “We don’t have to carry the hate from more than 24 years,” she said. “It’s not going to help us heal if we don’t forgive. For me, knowing that I can forgive is an achievement. And I understand women who cannot forgive yet because they have to heal first. Knowing the importance of forgiveness and then being able to forgive are two [different] things.”

In rural Rwandan villages, genocide survivors work side by side with the wives of jailed perpetrators. The reconciliation process and economic necessity have propelled the women to make peace in their neighborhoods and form job-producing cooperatives.

After sharing their stories with one another through the reconciliation process, “there is no hate between them,” Umugwaneza said. “There is nothing that separates them, because they say at the end of the day, we’re all Rwandans and we’re all women. The only thing we want is to raise our kids and to feed them and to just have a roof over their heads. If you can do that together, why not?”

Still, the three Rwandans want others to understand that genocide is not their country’s only legacy.

“Some people think that the genocide is still going on, and they don’t know there is peace today in Rwanda,” Uwase said. “But people should know that Rwanda is a beautiful country of a thousand hills. It’s a peaceful country now, which has resilient women and people who are really welcoming. They should visit.”

Your comments are welcome

1 Comment

Thank you very much for publishing this story! The title really could be “The Next Generation of Rwandan Leaders Educates TCU.” In Ambassador Hunt’s book, one of the best quotations is of Lawyer Agnes Mukabaranga saying, “Even though the new government wanted women to be involved, the mind-set wasn’t what it is now…. [T]he cultural idea was that politics wasn’t for women” (page 125). The mind-set and the cultural idea of Rwanda today offer much to us in the USA. The young leaders at TCU from Rwanda offer much to TCU with respect to the mind-set of the positive impact of women in leadership and the cultural ideas of diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Related reading:

Alumni, Features

Swanee Hunt Pushes for Inclusion of Women in Peace Building

The humanitarian champions women helping their countries recover from war.

Features

History of the Rwandan Genocide

Part of German East Africa from 1894 to 1918, Rwanda came under Belgian rule after World War I, along with neighboring Burundi. Both the Germans and Belgians favored the minority Tutsi, awarding them access to education and government posts. This angered the Hutus, who made up 85 percent of the population. In 1959, Hutus rebelled

Features

Crossing borders – TCU’s bond with Rwanda

As a child in Rwanda, Yannick Tona survived genocide to become a tireless promoter of tolerance and cross-cultural understanding.