Did you Fail? 7 Frogs Find Meaning in Life’s Wrong Turns

On the path to success, falling doesn’t mean you can’t fly.

Everyone fails, but few people are comfortable discussing it.

When I met with Joy Kendle ’14 at the Mary Couts Burnett Library, she said she wished she had known on graduation day that career paths weren’t always easy. When her ambitions stalled, Kendle learned that the road to success in corporate America was not guaranteed, even with a college degree.

I agree with Kendle. After misguided career attempts as a rock drummer and then as a literary fiction author, I know those life lessons are learned the hard way. Though I always managed to provide for myself and avert financial disaster, I was well into my 30s before I had a job with benefits.

Joy Kendle said the biggest obstacle was to overcome the naysayers. Photo by Mark Graham

I don’t know anyone who has sailed smooth seas in their career. Between the covers of each tale of success are untold stories of disappointment.

While Kendle is in her mid-20s, she has some perspective: “Just [become] comfortable with failing,” she told me. “It’s going to be OK. And people are going to love you, and it’s going to be all right because everybody fails.”

After experiencing failure, many people pick themselves up, wipe off the dust of calamity and carry on with a new nugget of wisdom. For example, Kendle is in the process of reinventing herself as an entrepreneur and app developer.

Admitting failure is no easy thing. Turns out, the TCU community is not comfortable with the concept either. While reporting this story — tracking down leads and whispers of failure — I hit brick walls trying to get people to share their experiences.

Kudos to the seven people who were willing to discuss their misadventures in life. I admire their courage and noted the wisdom they picked up in the midst of broken plans.

I hope, in these stories of a missed chances, addiction and career missteps, readers will savor the fruits of these experiences, and the redemptive rewards for the failures required to reach them.

Wisdom Found at the Deli Counter

Life’s easy stretches and sugary phases can be deceptive. A taste of success, especially early in a career, can lead to delusions about the road ahead.

A few years after posing with his college diploma on graduation day, Peter Duffy ’82 had simple career expectations: “If you lace it up every day, and you go to work with the intention of doing the right thing, and you work hard, you should achieve success,” he said.

Easy, right? One problem, he concluded: “Life is not like that.”

At first the post-collegiate career waters were warm and inviting. By Duffy’s mid-20s, he had transformed an entry-level job selling soaps and detergents for Procter & Gamble into a lucrative position as a district manager.

Peter Duffy learned that life’s valleys don’t always resolve automatically into peaks. Photo by Jörg Meyer

Duffy jumped into the workforce without much thought about what he really wanted to do for a living, he said. “I just knew I had bills and I wanted to work, and I wanted to be successful.”

Duffy became disillusioned with the ruthless profit-seeking of some people in sales. Procter & Gamble’s preferred structure limited the creative instincts of young professionals such as Duffy who saw different ways of doing things. Fault lines opened, undoing his idealistic vision.

When Duffy and his wife, Barbara, learned they were expecting their first child, the couple decided to move closer to family in New York City. Duffy left the Cincinnati-based global consumer goods company, rolling the dice and trusting that good fortune would follow.

“My timing was awful,” Duffy said, citing the economic downturn in the late 1980s and a nearly nonexistent job market.

After two bad jobs in as many years, Duffy became an unemployed father of two and was saddled with a hefty mortgage payment. The former sales manager took the only job he could find, as a sandwich maker at a Long Island delicatessen.

Duffy was portioning tuna salad on hoagie rolls just to pay the babysitter. “I was demoralized,” he said.

He had learned that life’s valleys don’t always resolve automatically into peaks. Duffy recalled the post-college path he had taken and decided to spend more time figuring out where he wanted to go.

“For quite a while, what I knew every day when I got up was I wasn’t going to quit. … I didn’t know what I was going to do other than not quit.”

Peter Duffy prepares for an upcoming triathalon in New York City. In his book The Courage of My Convictions, Duffy recounts how he rebuilt his career after his professional life crumbled. Photo by Jörg Meyer

After much reflection, Duffy realized he was out of touch with his life-direction compass. He had been throwing energy into jobs he wasn’t passionate about, so he hit pause on the stream of job applications and explored his heart to figure out what work was most appealing.

Duffy said his next career needed to be meaningful and people-centered and involve problem-solving. And for good measure, he wanted to incorporate his sales skills.

To that end, Duffy decided that working as a financial adviser would fulfill all his conditions. Duffy played recreational basketball with a man who owned a small brokerage, and he knocked until that man opened the door with a job offer.

Armed with a specific intent, Duffy saw his career take off. Soon after entering the field, he started speaking at conferences where bank and credit union professionals gathered to discuss mergers, risk and raising capital. Duffy eventually landed a job as a managing director at Sandler O’Neill and Partners, an investment banking firm with headquarters in New York that specializes in the financial services sector.

Duffy wrote a book about the ebbs and crests of his journey, The Courage of My Convictions (iUniverse, 2004). His first failure sprang from an inability to be honest with himself about what he wanted out of work, Duffy said. The second failure was not choosing to do something he loved. And third, he said, was spending more money than he was earning.

Fixing those problems meant more success, Duffy said. “If you do them, you’re successful by your own measure, and that’s the only measure that matters.”

Purpose in Not Passing

Felicia Jernigan Browning ’81 never imagined the pitfalls presented on the path of higher education, but then again she never imagined she would attend college.

Felicia Jernigan Browning stands in a nursing classroom where she teaches in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. Photo by Chuck Cook

As a senior at Fort Worth’s R.L. Paschal High School, Browning had a good job as an accounts-payable clerk at a soda bottling plant and planned to make it a full-time gig after high school. Even though she lived just a few miles from TCU, she had never stepped foot on the campus until rehearsal for Paschal’s graduation ceremony.

As fate goes, Browning ran “smack into” Elizabeth “Libby” Proffer, dean of students at the time. Proffer took an interest in the teenager, showed her around and “pretty much registered me that day,” Browning said.

Browning’s TCU days began with general thoughts of a major in English. Then she walked into a nursing lab class. “They were doing assessments on each other in the lab and giving shots to oranges,” she said. “And I thought, ‘That’s the coolest thing ever.’ ”

A scholarship from the Girls’ Service League of Fort Worth sealed the deal. The more Browning experienced in the field of nursing — including an assignment to care for a nonverbal, immobile stroke patient — the more Browning knew it was her life’s calling.

The last semester before her college graduation, Browning worked in the neonatal intensive care unit at Fort Worth Children’s Hospital. She was offered a job in the nursery upon graduation. She accepted, signing her name with G.N. for graduate nurse while waiting to take the exams for her license.

The Girls’ Service League encouraged Browning to enroll in a hospital administration master’s degree program. She was considering it. But then her career plans unraveled. Browning didn’t pass her exams. Neither did her best friend, Gail Smith Towe ’81.

“It was devastating,” Towe said. “You’re embarrassed. Your self-confidence kind of buckets. … I didn’t know what my life was going to be.”

“After I had seen an impact that I could make, I didn’t want to just pay bills.”

Felicia Jernigan Browning

“It would have been real easy to fall into a black depression over it,” Browning said. “Because what do you do with a degree in nursing with no license? But I was absolutely determined that I was going to be successful at this because I feared that I would end up working at the bottling company again. After I had seen an impact that I could make, I didn’t want to just pay bills.”

Browning, Towe and a passel of classmates took review courses offered by their former professors at the Harris College of Nursing & Health Sciences. They passed the second time with no problems.

Browning got that nursing job at the children’s hospital and worked there for the better part of a decade while her husband, Dan, studied at a nearby seminary. The couple moved to Hattiesburg, Mississippi, where he joined the William Carey University faculty.

Browning excelled in Hattiesburg. She was promoted to manager of a neonatal intensive care unit and then to director of nursing. The veteran nurse said she disliked the administrative duties of the director’s job, realizing that her path wasn’t meant to lead to the master’s degree in administration that she never pursued because of that failed exam.

Felicia Jernigan Browning kept her nametags as she transitioned from job to job. She displays them in her office as a reminder that sometimes obstacles are good things. Photo by Chuck Cook

When Browning recently told her story, she hit her fist on a Fort Worth coffee shop table to emphasize that “I love nursing. … I can’t think of having done anything else. Ever.”

William Carey University offered Browning a teaching position, so she went back to school for a master’s degree in nursing education, not administration.

Even though she is semi-retired, Browning continues as an adjunct professor. She has found she loves mentoring almost as much as nursing. She has plentiful opportunities to counsel nurses who don’t pass their exams or otherwise stumble in the demanding career path.

In her faculty office, Browning has a shadow box containing nametags from the roughly two dozen jobs she has had. “You see that one right there,” she tells strugglers who are seeking her advice, pointing to that G.N. role in the nursery. “That name badge lasted a year because I didn’t pass my boards either.”

Browning said the message people remember — and the one she learned through failing — is about the foundation of the plan. “I would bring back, ‘Remember when you were in here being advised, and you told me why you wanted to be a nurse?’ And I make them come back to that memory of how excited they were to get accepted into the program and to want to be a nurse.”

Addiction and Resilience

(Editor’s Note: Because of the personal stories around substance abuse and addiction, the last names of two alumni are withheld in this section.)

For some college students, failures related to partying too hard can derail education goals. Instead of planning careers or choosing academic majors, students who struggle with addiction can spend their time worrying about expulsion or why they woke up in a hospital.

Caroline Albritton, program specialist in the alcohol and drug education office in the Department of Student Affairs, runs a program to help with student recovery. Photo by Mark Graham

The National Institute on Drug Abuse reports that about a third of college students will binge-drink in any given month. At TCU, a 2017 survey administered by the university’s Office of Alcohol and Drug Education showed that 11.5 percent of undergraduates believed they might have a substance abuse issue.

“The fear of missing out, or FOMO. It’s a very real thing, and … unfortunately in a college setting, alcohol can be very much a part of that,” said Caroline Albritton ’13 MEd, a program specialist in the alcohol and drug education office in the Department of Student Affairs. She counsels students and runs a collegiate recovery group where addicts discuss reassembling the pieces of their lives.

For Nick, who graduated in 2018 with a degree in environmental science, experimenting with intoxicants, spurred by social anxiety, started in middle school. He said he wanted a new start in college but continued down the same path.

In his freshman year, campus police caught Nick smoking pot in a dormitory. At the Campus Life office, counselors doled out a strong warning about expulsion and required Nick to complete 100 hours of community service to remain at the university.

Time spent answering a crisis hotline expanded Nick’s perspective. “I learned that I wasn’t the center of the universe,” he said. “I’m not the only one with problems, and I can’t just do the first thing that comes to my mind whenever I get uncomfortable.”

By his junior year, Nick was alienating friends and was barely hanging on in his classes. One night while drunk and delusional, Nick tried to fight a bouncer at a local bar. He said he even planned to return to the venue with a knife. When the absurdity of his intent washed over him, Nick said, “Something deep down reached up to me and said, ‘This is not the person I am. This is not what I want to be. This is never what I wanted to happen.’ ”

Albritton said Nick’s rock bottom was his breakthrough moment. “It’s really difficult to admit powerlessness to a substance,” Albritton said. “It’s almost like weakness. … It takes a very strong and courageous individual to be able to say, ‘I struggle with this.’ ”

As a recovery group facilitator, Albritton hears stories very similar to Nick’s, and she said she never stops being impressed by the self-awareness that people exhibit in recovery. “It’s pretty remarkable to be able to see that student have that light bulb moment … [to realize] what I’ve been doing isn’t working,” she said. “And as scary as it is to change what I’ve been doing, there is a solution.”

Nick found the therapy he was seeking. “I realized what I really needed the most was just to talk to people that were like me.”

Nick met Jordan, who graduated in 2018 with a degree in marketing. She told the collegiate recovery group about her eating disorder, alcoholism and prescription drug abuse. But Jordan’s rock bottom spanned a few months. She woke up in a hospital without any memory of how she got there. Her addiction also ruined a marketing internship because she was wasted at a company function.

Two disorderly conduct violations led to Jordan’s encounter with Campus Life. Knowing she had lost any pretense of perfection, she broke down during a meeting with a senior faculty administrator.

“This was the first time I ever got in trouble for anything,” Jordan said. “I just remember crying and being so confused [about] why this happened to me because I didn’t do anything wrong, and it’s not my fault. Blaming everybody else for what’s going on.”

Jordan eventually stopped drinking and started attending the recovery group meetings on campus. “Admitting that I had a problem was really relieving,” she said. “And finding the group was probably the best thing that’s happened to me.”

“What other people think about me is none of my business. But what I think and what I feel about myself is most important. And that was huge for me.”

Jordan

But many of Jordan’s friends didn’t agree with her new lifestyle choices and stopped returning her text messages. “I lost friends, but I’ve made new relationships with people who genuinely care about me and take it with me one day at a time,” she said.

Even though the social rejection stung and she felt like a failure, Jordan gained some perspective: “What other people think about me is none of my business,” she said. “But what I think and what I feel about myself is most important. And that was huge for me.”

By redirecting his path, Nick said he used the resources on campus to construct a sturdier foundation for whatever life throws at him. “There’s no secret way to just make all difficulty that makes life, well, life, go away,” he said. “You kind of just need to live life the way it is.”

Nick made new friends in the recovery group, and they attended basketball games and made terrariums in search of sober fun. He also took up yoga and rock climbing.

Jordan said she was reluctant to attend sporting events because of the drinking culture, but she learned to adjust to a sober lifestyle. “My life is so much better now,” she said after almost a year of sobriety.

Near their graduations, Albritton advised Nick and Jordan not to dwell on mistakes, that they had been through the hard part and had emerged just fine. “It’s really only failure if it does become a dead end for you,” Albritton said. “If it’s just a speed bump, it’s not really failure. That was a learning experience that really helped you grow and develop.”

Perspective on a Missed Opportunity

Mark Zuckerberg has made more than $70 billion with his vision for Facebook. Those riches could have belonged to Michael Sherrod ’10 MBA, instructor of management at the Neeley School of Business.

Michael Sherrod, instructor of management at the Neeley School of Business, teaches his students every success begins with a failure. Photo by Mark Graham

As a reward for selling his startup DigitalCity to America Online in 1999, the tech behemoth named Sherrod leader of its social media division, which in the burgeoning internet days was called “community.”

Sherrod said he saw the potential. He collected stacks of user analytics. The data was staring back at him. “Ninety percent of all of the time our subscribers spent on AOL, behind the paywall, was in community products and services,” which back then meant open journaling pages, message boards and the social-minded member directory.

The latter, Sherrod said, “was Facebook, literally. It looked exactly like it does now.”

Instead of seeing the opportunity before him, Sherrod focused on the short-term details of his daily job. “I had the data right in front of me that people loved to be where their friends were and engage with their friends. And I didn’t expand that to the outside world,” he said. “That was my biggest failure.”

But this wasn’t Sherrod’s first failure. As a serial entrepreneur, the now-teacher of aspiring businesspeople started out in the publishing industry. He began with a lifestyle magazine in Odessa, Texas, which was profitable from the get-go, he said. “I was making more money than I ever thought I’d make in my life.”

Flush with cash, Sherrod started an ad agency and a graphic design business. Everything he touched seemed to turn to gold — until he decided to publish a cookbook. He spent $750,000 renting a test kitchen, hiring chefs and photographers, and buying food.

Knee-deep in the project, Sherrod had a realization: “I didn’t like cooking. I was not a person who cooked,” he said. “I didn’t understand it very well. I did not know how expensive it was to publish cookbooks.”

“Students love to hear about failure. Any time an entrepreneur comes, they’re much more interested in their failure stories than they are in their success stories.”

Michael Sherrod

Sherrod pulled the plug, licked his wounds and waved goodbye to almost a million dollars. “If you’re just trying to make money, it’s going to be really hard to be successful as an entrepreneur,” he said. “You have to really care.”

Scores of opportunities and experiences later — including helping lead a $300 million sale of Ancestry.com to a private equity group and being the first publisher of The Texas Tribune — Sherrod packed up his experiential wisdom and took it to the classroom as TCU’s William M. Dickey entrepreneur in residence.

Sherrod now guides students as they learn about everything it takes to come up with an idea and execute it in a profitable manner.

He said the most valuable advice he offers revolves around failure. That’s “where it all starts. Almost all of the great entrepreneurial companies you see out there are based on a failure,” he said, citing YouTube — the founders were aiming for a video dating service.

Michael Sherrod said almost all great entrepreneurial companies started with failure. Photo by Mark Graham

“Students love to hear about failure,” Sherrod said. “Any time an entrepreneur comes, they’re much more interested in their failure stories than they are in their success stories.”

Part of the reason for their insatiable interest in the gory details of business disasters is the nearly taboo nature of the subject in U.S. culture, he said. “We have a very stunted view of what failure is, really … and how it actually works in our lives.”

Considering the technological disruption changing every industry, from machines writing summaries of sporting events to robots performing surgeries, Sherrod teaches that career failure is something everyone will face at some point. “We have to learn how to deal with it and how to catalog it differently than we do now in our brains.”

Failure is part of the process, Sherrod said, and something to be embraced rather than avoided. “Because if you don’t have failures, you’re not going to have very many successes either, because you’re not learning anything.”

Ingenuity and Joy

After graduating a semester early, Joy Kendle was ready to get her post-college life underway. Her expectations: job, apartment, eventually a family.

Joy Kendle created an app to connect people who need babysitters with reliable college students. Photo by Mark Graham

Kendle checked the job part off in a hurry, accepting the first offer she got and believing her communication studies degree would serve her well in the insurance industry.

One problem: “It was awful.”

Kendle took claims from people in the aftermath of car accidents and bodily injuries for about three months before resigning. Unemployed, she reached out to a few babysitting clients from her college days.

Three years later, Kendle was a nanny for the same family she asked for some temporary babysitting shifts. She didn’t intend to stay so long. About a year into the gig, she applied for at least 60 jobs, in human resources departments and for executive assistant positions. The result of all that? Radio silence. Not a single interview.

“You have that mindset: If you have a college degree, you’re going to get jobs,” Kendle said. But in a maze of dead-end roads, “I was feeling kind of frustrated and stuck.”

Friends and acquaintances made acerbic comments about wasting her degree, which compounded her worries about failing to launch.

Kendle said she feared her temporary job as a nanny was evolving into an inescapable — and undesired — career. She enjoyed working with kids, but she wanted more out of life.

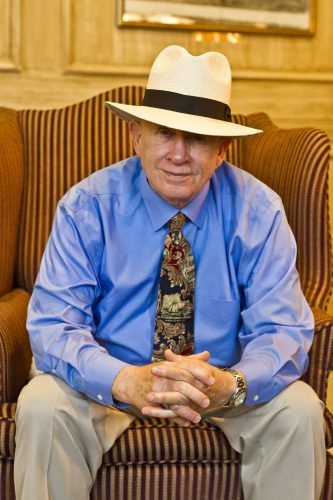

John Thompson spent decades counseling TCU students and alumni on their careers. Self-reflection and taking ownership, in his opinion, are key to not being undone by failure. Photo by Mark Graham

Her unmet career expectations are a common hurdle in the working world, said John Thompson ’63 (MBA’69), former executive director of the Center for Career and Professional Development at TCU. “Failure can be a really big motivator. Or it can drive you to the cave, never to be heard from again.”

Kendle wasn’t ready to give up on her career but didn’t know where to turn. One night her clients saw her frustration and sat down with her to brainstorm a way out of the career quagmire.

Kendle’s idea was an app that would connect her TCU network with Fort Worth families seeking reliable child care. She went home and wrote her idea in a notebook. She knows the date of the entry by heart: Dec. 30, 2015.

QuickSit connects babysitters with verified tcu.edu addresses to Fort Worth families. The app, which includes reviews of the sitters, is in testing and should launch in spring 2019. Kendle has plans to expand it to additional Texas markets.

“Ever since I came up with the idea, whether it succeeds or fails, I feel like I really had some purpose,” Kendle said.

From writing a business plan to finding investors and then hiring marketers, app developers, an accountant and an attorney, Kendle has learned a lot — her experiences became the basis for a plan of action.

The biggest challenge, she said, was overcoming the naysayer in her head. “It’s mentally hard to push past the doubts and the fears of ‘I’m so young, and I’ve never started a business before, and I don’t have the highest income, and I don’t have the biggest investors,’ ” she said. “They can either stop you or you just, like, use them as some fuel and just keep going.”

Failure would have been staying stuck, Kendle said. “You just have to keep pushing forward and being flexible with whatever you have, because you can definitely make something out of whatever your situation is.”

Your comments are welcome

1 Comment

Failure is the greatest teacher.

Related reading:

Features

Kathy Cavins-Tull Talks About Failure-Based Lessons

In a Q&A, the vice chancellor for student affairs talks about how TCU’s safety net stands to help students succeed.

Features, Research + Discovery

Failure on a Small Scale: Tiny Holes Elude Silicon Researchers

Professor Jeffery Coffer doesn’t allow frustration to get in the way of solving a riddle.

Letters

College Is All About Learning from Mistakes

You might have read or heard this popular story about failure. As a young man, Walt Disney was fired from a Missouri newspaper. An editor told him he “lacked creativity.”