When TCU first loved football

A dangerous, new game imported from back East eventually helped a tiny university grow. But it almost never caught on.

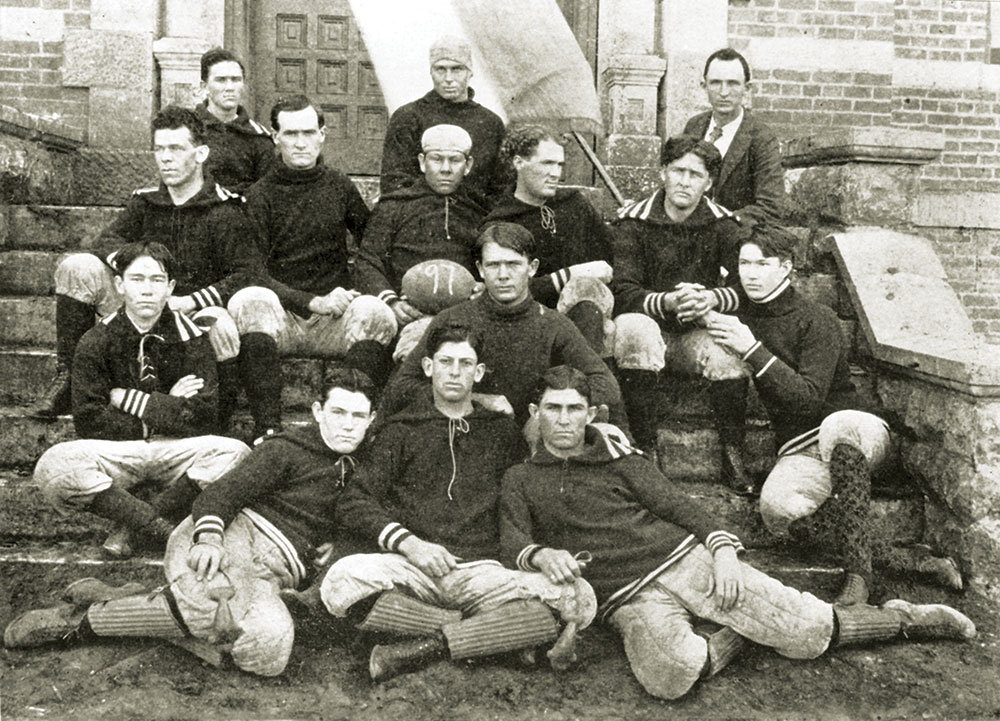

The first-ever 1897 Add-Ran football team, nicknamed “the Boys from the Heights.” (Photography courtesy TCU Special Collections)

When TCU first loved football

A dangerous, new game imported from back East eventually helped a tiny university grow. But it almost never caught on.

Editor’s note: More than a century ago, TCU football faced an uphill battle for acceptance from a skeptical administration, but Addison Clark Jr. — or “Little Addie” — was a pivotal fan who, along with Aaron C. Easley, Joe Field and the Boys from the Heights, put TCU on the path to gridiron greatness. This excerpt and images, from the new TCU Press book, Riff, Ram, Bah, Zoo! Football Comes To TCU by Ezra Hood ’95, details some of those early years.

One 1895 Add-Ran College alum “often enthused over his own football experiences [in Thorp Spring] before his graduation.” Those experiences would have been exclusively intramural. Add-Ran did not have any intercollegiate sports yet, but the baseball and football games between students were organized well enough to warrant attention in the Collegian, the school paper published in Thorp Spring before Add-Ran moved to Waco. But football and baseball took a back seat to military drill, which was the most popular organized extracurricular activity for students at Add-Ran, much as it was in colleges all across the old South. Two companies were formed at Add-Ran College in 1895.

An anti-sports attitude in the administration at Add-Ran, beginning with Addison Clark himself, posed a bigger obstacle to football than the popularity of military drill. Clark, like most older men of his generation, had little use or tolerance for sports. He preferred that the virtues of strength and endurance be acquired by work, not by frivolity. He made an exception to his somber lifestyle for hiking, and would often lead the boys on hikes up to 20 miles across the country.

An 1876-77 school catalogue described the near-Puritan expectation for student culture in that early day. The students were: “to have neither the time nor the desire for miscellaneous gallantry, or letter writing. … That they attend no exhibition of immoral tendency; no race course, theatre, circus, billiard saloon, bar-room, or tippling house . … That they abstain from profanity, the desecration of the Lord’s Day, all kinds of gaming for a reward or prize of any kind, and from card playing even for amusement. … That they attend public worship every Lord’s Day.”

An 1876-77 school catalogue described the near-Puritan expectation for student culture in that early day. The students were: “to have neither the time nor the desire for miscellaneous gallantry, or letter writing. … That they attend no exhibition of immoral tendency; no race course, theatre, circus, billiard saloon, bar-room, or tippling house . … That they abstain from profanity, the desecration of the Lord’s Day, all kinds of gaming for a reward or prize of any kind, and from card playing even for amusement. … That they attend public worship every Lord’s Day.”

Alcohol consumption and tobacco use were likewise prohibited, as was leaving the college without permission. Uniforms, although not required until 1882, were wool and gray (with checked gingham aprons for the girls). Jewelry and hairdos with bangs were forbidden. The school administrators checked on the students in their rooms nightly, and boasted of the orderliness they observed (or enforced).

The college prohibited dating with appalling zeal. One co-ed was reprimanded for walking across campus with a male student — her brother! — because it gave the appearance of evil. Shortly before commencement in 1892, a male student was found to have walked his fiancée from town to her house, and was immediately and publicly expelled. Other students petitioned Addison Clark to reinstate the student, saying that they all had stolen privileges at one time or another during their years at school. Clark responded by expelling all of them, too, prompting the school’s first admissions crisis. Mrs. Jarvis, who was Add-Ran’s headmistress of housing for women, interceded on behalf of the expelled students, and Clark relented — and began the practice of hosting monthly socials for the students. These socials may have been a revival of an earlier tradition: one Add-Ran alum recalled talking a girl to sleep at one of the regular soirees the school held during its Thorp Spring days.

Clark eventually proved flexible regarding sports on campus, as well. Clark’s son, “Little Addie,” returned from studies at the University of Michigan in 1896 with an abiding enthusiasm for football. After Addie was hired on at Add-Ran to teach, his father Addison warmed to the game — or to his son’s enthusiasm for it — and ceased opposing it on campus. This remarkable turnaround is the first significant debt that TCU football fans owe to Midwestern football.

The second debt to the Midwest came in the person of Aaron C. Easley, one of six children of William and Phoebe Easley, who had originally come to Texas in 1871 and staked a claim near the Red River. In 1882, William brought Aaron and his younger brother 100 miles by wagon to Add-Ran’s campus. “I know you are going to make good,” said his father, “and we are going to do our best to bring you back (home) every year ’til you graduate, and then we are counting on you to help us put the other children through college.” (A.C. fulfilled that responsibility; his sister Julia Easley Robertson — an 1896 graduate — was on the committee that recommended purple and white as school colors.)

The second debt to the Midwest came in the person of Aaron C. Easley, one of six children of William and Phoebe Easley, who had originally come to Texas in 1871 and staked a claim near the Red River. In 1882, William brought Aaron and his younger brother 100 miles by wagon to Add-Ran’s campus. “I know you are going to make good,” said his father, “and we are going to do our best to bring you back (home) every year ’til you graduate, and then we are counting on you to help us put the other children through college.” (A.C. fulfilled that responsibility; his sister Julia Easley Robertson — an 1896 graduate — was on the committee that recommended purple and white as school colors.)

William set out with the wagon once again to bring A.C. home from school after his first year. Forty miles from Thorp Spring, he succumbed to pneumonia, and died one day before his son was able to reach him. The saddened student borrowed a horse for the journey home. “I shall never forget the feeling of responsibility that swept over me as I rode up to the house and Mother and my brothers and sisters ran out to meet me. It looked like my chance for an education was gone.”

A.C.’s younger brother was old enough to tend the farm by 1885, and A.C. returned to Add-Ran, taking the same job he had before: doing chores at the residents’ homes and sweeping and making fires in the school building. A.C. married an Add-Ran student and joined the faculty after graduating. Family lore credits Easley for first suggesting to the Christian Church that it purchase TCU.

Easley went to the Midwest in the summer of 1896 to study at the University of Chicago, which had been established just five years earlier. While in Chicago, he became a fan of the new sport from the East. He met Alonzo Stagg and obtained a new football rulebook from him. He returned to Waco in the fall and joined little Addie in organizing a football game among the students on Thanksgiving Day 1896. Different colored stockings sufficed for uniforms: one team wore brown, the other black. They played three more games after Thanksgiving, beating Toby’s Business College, losing to Houston’s Heavyweights, 22-0, on Dec. 19, and then tying Houston’s Heavyweights in the rematch sometime later that month. The “season” was a draw, as the team finished with a 1-1-1 record.

Easley went to the Midwest in the summer of 1896 to study at the University of Chicago, which had been established just five years earlier. While in Chicago, he became a fan of the new sport from the East. He met Alonzo Stagg and obtained a new football rulebook from him. He returned to Waco in the fall and joined little Addie in organizing a football game among the students on Thanksgiving Day 1896. Different colored stockings sufficed for uniforms: one team wore brown, the other black. They played three more games after Thanksgiving, beating Toby’s Business College, losing to Houston’s Heavyweights, 22-0, on Dec. 19, and then tying Houston’s Heavyweights in the rematch sometime later that month. The “season” was a draw, as the team finished with a 1-1-1 record.

An athletic association was formed that leased a field on the southwest corner of the Waco campus early in January 1897. Addison Clark had become so much a supporter of football, and athletics in general, that he argued in favor of intercollegiate play in other Texas cities before a skeptical Board of Trustees early that year. The board grudgingly added the “requirement of athletic exercises as a part of University courses,” but refused to allow the football team to play at College Station, Austin, or Houston — even though Clark had already accepted invitations to play from A&M, UT and a Houston team. Discouraged, but not disbanded, the school’s football enthusiasts pressed forward, reorganizing the Athletic Association in September, and appointing as manager W.O. Stephens, who filled most of the functions of a modern athletic director and equipment manager. Stephens raised enough money to hire a coach, Joe Y. Field, who arrived on Oct. 1.

Field coached Add-Ran’s first memorable team, called sometimes the “Boys from the Heights” of north Waco. No Horned Frogs would match them for a decade. Years later, M.R. Sharp would reminisce about how there were “only about 30 boys in school — yet they had a winning football club.” The lineup was left end Frank Pruett, left tackle Guy Green, left guard W.G. Carnahan, center Sam Rutledge (in 1903 still called TCU’s best center to date), right guard (and future athletic director) C.I. Alexander, right tackle R. Earle Sparks, right end Claude McClellan, who was also the captain, quarterback C.W. Herring, left halfback M.R. Sharp, right halfback Jim V. McClintic and fullback Jeff R. Sypert. S.S. Glasscock, R. Holt, G.A. Foote and H.E. Field played backup.

Add-Ran’s athletic association won permission from the Board of Trustees to travel out of Waco for games two weeks before the opener against a team in Dallas that was unaffiliated with any college. Add-Ran won 6-0. Traveling apparently suited the Horned Frogs, for they were one of the first college teams ever to score on University of Texas. The Wacoans played the Austinites “to a standstill,” losing, 16-10 (one account lists the score 18-10). Texas A&M and Fort Worth University, on the other hand, were no match for the upstarts from north Waco, losing 30-6 and 32-0, respectively.

Perhaps Coach Field’s players’ success stemmed from their training regimen, laid down by the coach:

1. Abstain from all intoxicants, also coffee and tobacco.

2. Go to bed at 10.

3. Eat no sweets or pastry.

4. Indulge in no kinds of dissipation.

Or perhaps the success came from the team’s new mascot, the horned frog, which was a common lizard in central Texas before fire ants migrated to Texas in the 1950s and drove the horned frog away. It could have been stimulated by the school’s new colors, purple and white, chosen by representative co-eds from both of Add-Ran’s literary societies. (The team wore blue on its uniforms, however, until 1912.)

Add Ran’s 3-1-0 record in 1897 would be its best mark for the following decade, which was darkened first by strangling opposition from the administration, and then by a stretch of losses so demoralizing that the school nearly quit the sport altogether. It is doubtful that the school actually awarded letters at the end of the 1897 season, but today TCU recognizes 16 letter winners from that year — the entire team.

Riff, Ram, Bah, Zoo! Football Comes to TCU is available through TCU Press by calling 1.800.826.8911.

On the Web:

Read a Q & A with author Ezra Hood on how he researched and wrote Riff, Ram, Bah, Zoo! Football Comes to TCU.

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related Reading:

Features

A Prescription for Success

TCU’s health policy program from the Neeley School of Business trains medical industry professionals in the business of health care.

Features

Campus of the Future

TCU’s Campus Master Plan builds on the university’s vision and values.