First person: Jim Swink ’57

It’s been 50 years since Ol’ Swivel Hips Jim Swink ’57 galloped on the TCU gridiron. We say he still should have won the Heisman Trophy in 1955. He says he doesn’t know what he’s missing and that suits him just fine.

First person: Jim Swink ’57

It’s been 50 years since Ol’ Swivel Hips Jim Swink ’57 galloped on the TCU gridiron. We say he still should have won the Heisman Trophy in 1955. He says he doesn’t know what he’s missing and that suits him just fine.

You suffered a stroke earlier this year, affecting your left side, but it looks like you could outrace anybody in a pair of cleats. How is your recovery coming? Very well. I fell and injured my hip and that slowed my recovery a bit. But I think I just might make it. [Laughs] Wife Jeanie adds: “He better.”

So can we still call you Swivel Hips — or did you prefer the Rusk Rambler? Oh, those are just things the sportswriters made up in those days. I never liked one over the other. I really never paid much attention to that. I was just happy to be playing and having a good time.

So can we still call you Swivel Hips — or did you prefer the Rusk Rambler? Oh, those are just things the sportswriters made up in those days. I never liked one over the other. I really never paid much attention to that. I was just happy to be playing and having a good time.

You played both offense and defense in those days. What kind of a tackler were you? I played cornerback, so I wasn’t the best tackler on the team by a long shot. They just put me over there because I was fast. They knew I couldn’t tackle, but they also didn’t want me to get hurt.

Who was the toughest guy to bring down? Jim Brown.

You tried to tackle the immortal Jim Brown? Me and three or four other guys. He was a man among boys, even at the professional level. He was that good.

But your team got the better of his in the 1957 Cotton Bowl? We had the better overall team. One player doesn’t make a team. A player is only as good as his blockers. That was true of me.

Yes, but you had an extraordinary season in 1955 as a junior — 1,283 yards, an average of 8.2 yards per rush, 18 touchdowns. How did they ever give the Heisman Trophy to Howard Cassady that year? It’s just one of those things. I think my statistics compared favorably with his, but he was a senior and I was a junior. They almost never gave it to anyone other than a senior and hardly to anyone from the South. But it wasn’t as big a thing as it is now.

So you weren’t upset or disappointed? Well, I did want to be recognized because it would have been an achievement for our team. But in those days you usually found out about it after the season. That’s how I found out I was even on the list — I read it in the newspaper.

In your senior season, did TCU hype you as a Heisman candidate? No. We didn’t have as good a team that season. We lost several of our best players. Teams we played kind of ganged up on me.

That must have been frustrating. Just part of the game.

You still went to the Cotton Bowl. You didn’t mind playing decoy? I caught more passes that year. But we lost some of our best blockers. Runners are only as good as their blockers.

What was it like to be recruited by and play for Abe Martin? I grew up in a small town in East Texas, and he came to see me play in a game of the seniors against the returning players. There was nothing unusual. They just said that he called his wife and told her he wasn’t coming home until he signed me to come to TCU. But he was a likeable man, made a good impression. I had visited most of the Texas schools, but TCU made me feel like they wanted me.

So he made you feel wanted more than other coaches? Yes. But I also liked how TCU had a small town feel to it back in the 1950s. So I always felt lucky that I had enough sense to go there. I liked my teammates and coaches. You know, the other reason I picked TCU was because of a real good player I played against in high school. His name was Hugh Pitts. He was a grade ahead of me, but I was tired of playing against him. He was already going to TCU so I decided it would be smart to play on his team.

What was Coach Martin’s style like? Players just liked him. He was more like a father figure to us later. He’d put his arm around you and tell you that next year you’d be starting at this position. I don’t know how many he told that.

Was he harder on you than some of your teammates? He was easy on me. He treated some of the best players differently. Never raised his voice. He believed in us, encouraged us. He was the sort of man you wanted to do good for — not just for yourself, but for him. But his method was soft sell, not hard nosed. That suited me just fine.

As great as you were and as big a recruit as you were, you had to play on the freshmen Wog team like everyone else. What was that like? We only played four or five games. And our team, the offense, the plays we ran – none of it was very organized. Jim Taylor was the coach, and the thing that I appreciate was the fact that he never gave up on me. I remember the very first game we played Tarleton down in Stephenville and the lights at their stadium weren’t’ very good. I was fielding a punt and I misjudged the ball in the lights. It hit directly on my shoulder pad and then bounced what seemed like 40 yards behind me. The other team recovered, and I thought I wouldn’t get to play again for a long time. But he sent me back out there. I was always grateful he didn’t write me off after that sterling play.

Was the 1955 team the best since the 1938 national championship team? I thought we were a good team. Even during the season I thought that. I think we averaged like 30 or 35 points a game. I just felt real fortunate to play with all those good players: Norm Hamilton, Hugh Pitts, Bryan Engram, Ray Taylor. We’re all still friends. They liked nothing more than my success because they were responsible for it. You’re only as good as your teammates.

I imagine the game against Texas is your favorite. Yes, people always talk about the 60-yard run. That was probably my greatest game. I always wanted to beat Texas and we usually did. But I am disappointed we didn’t beat A&M more though.

Is it true that the “Hook ‘em, Horns” slogan came about because of you and that 1955 team? They had a guy in their student body that knew our team and spread the word that they needed to stop me from running. The Texas players obviously had heard about how strong a team we had, too. So they came up with “hook him” because they wanted to catch me, trip me up, slow me down. And that game was the first time they used that. They also lit a bunch of orange candles before the game.

Someone said it was enough to burn down Austin. A reporter asked me what we did about those candles. I just said, “We blew them all out.”

What was it like to play in front of 60,000 people who all want you to fail? After the first play of the game, I don’t even notice. At all games, no matter the size of the crowd, they’re either for you or against you.

What teams did you really want to beat? Who did you consider your biggest rival? Well, I always wanted to beat Texas, and we did. I am a little disappointed that we didn’t beat Texas A&M more though.

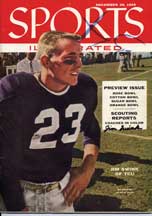

What did being on the cover of Sports Illustrated mean to you? It was special because it was one of four or five popular magazines. People still mail me copies of that issue – some for me to sign, some for me to keep. In fact, we have a stack of them at home that need to be signed. If I live to be 80, I think I’ll take up fishing and signing autographs. [Laughs.]

I think you remain the only TCU athlete to appear on the cover as a Horned Frog. I didn’t know that. You can see my nose all skinned up. They took that photo toward the end of the season. We didn’t wear face masks until my senior year. Your helmet would slide down and scratch up your nose and face. You can always tell how far a player was into a season by the cuts on his face.

You were a very clean-cut, articulate young man while at TCU, always speaking to the student body at pep rallies. The university had to have loved your great image and personality. Did you ever feel like you were an ambassador for TCU? I don’t know that I would put it that way, but I knew people were watching me when I wasn’t playing football. Kids used to come to campus early when we had day games. They would come to our dorm rooms and wanted us to sneak them into the games. They really were fans.

Did you sneak a kid into the stadium? Yes, along with lots of other players. After the game, they all asked for my chinstrap. That was the thing – the chinstrap. I have no idea why.

What do you think made you such a great runner? Just natural ability. I grew up playing lots of basketball. A lot of agility and eye-hand coordination came from that. I probably had good balance. Running is easy. All you have to do is run.

You had a single-bar face mask your senior year, the first year you had to wear one. Yes, and I didn’t like it. That bar was only as thick as your pinky finger. It didn’t protect much and helmets still slid down our faces and cut us up.

Did it obstruct your vision? Not really. But I wasn’t used to it. Playing the game just had a different feel to it. I guess I had gone without one for so long that it felt strange more than anything.

Did it offer any protection at all? Seems like it was more a hassle than anything else. Actually, it gave tacklers something to grab on to. We didn’t have a facemask rule. That came along later.

Why did you go into medicine? I grew up in a small town and was fond of the town doctor. When I got to TCU I started out in geology but didn’t much care for it. So I switched to pre-med. But organic chemistry almost made me change my mind.

What’s next for you and Jeanie? Once I get fully recovered, we’re moving back to Rusk. I want to work at the hospital there, sort of return to be that small town doctor.

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related Reading:

Sports: Riff Ram

Iron Man: Kaz Kazadi

The human performance specialist leads TCU Football’s strength and conditioning program into a new era.

Sports: Riff Ram

Lady Lightning

Record-setting sprinter Iyana Gray excels in arenas athletic and academic.