Swanee Hunt Pushes for Inclusion of Women in Peace Building

The humanitarian champions women helping their countries recover from war.

More than a decade ago, Swanee Hunt ’72 traveled to Rwanda and met with a group of women widowed by the country’s 1994 genocide. She sat with a 30-year-old named Fatima whose children had been killed during the conflict. Soldiers had raped her repeatedly, and Fatima had contracted AIDS.

The Rwandan woman offered her thin hand to Hunt, who took it in her own. “Is it all right if I tell your story?” Hunt asked, knowing Fatima wouldn’t live much longer. “Yes, please do,” Fatima answered, “so it doesn’t die with me.”

Hunt fulfilled her promise, writing Fatima’s story and those of nearly 90 other women in her fourth book, Rwandan Women Rising (Duke University Press), which was published in mid-2017.

The project echoed Hunt’s first book, This Was Not Our War: Bosnian Women Reclaiming the Peace (Duke University Press, 2004), which also used women’s own words to explain how they endured devastating warfare, then worked to rebuild their country. Through her travels to dozens of countries and in her work on university campuses and in Washington, D.C., Hunt has collected women’s narratives and woven them into articles and lectures.

As U.S. ambassador to Austria, Hunt met with President Bill Clinton in the Oval Office in 1994. Courtesy of Swanee Hunt

Hunt’s own story is full of adventure, accomplishment, heartbreak and triumph. Each chapter builds on the momentum of the one before, as Hunt, now 68, finds her voice and then helps other women find theirs. She becomes a philanthropist, the U.S. ambassador to Austria, a professor and an international advocate for women’s inclusion in government and peace building.

Formative Years

The youngest child of legendary oilman H.L. Hunt, Swanee grew up surrounded by privilege but often longed for a normal life. Her early years were unusual for reasons beyond her father’s vast fortune. H.L. Hunt fathered 15 children with three women, and Swanee and her four siblings (one of whom only lived a few days) were born while her father was still married to his first wife.

After his wife’s death, H.L. Hunt moved Swanee, her siblings and her mother into his Dallas mansion, and her parents married. Her father kept a high profile, sharing his ultraconservative views on radio programs. Tour buses filled with gawkers stopped daily at the edge of his property. Her father, a crusader against communism, believed the Ivy League was a training ground for the enemy. Her mother once described the women’s movement as “worse than drugs.”

Swanee Hunt taught at Harvard University for nearly two decades, and her feminism informs every decision she makes. Yet in her 2006 memoir, Half-Life of a Zealot (Duke University Press), she credits her parents with inspiring her with the intensity of their convictions — even though her beliefs diverged from theirs.

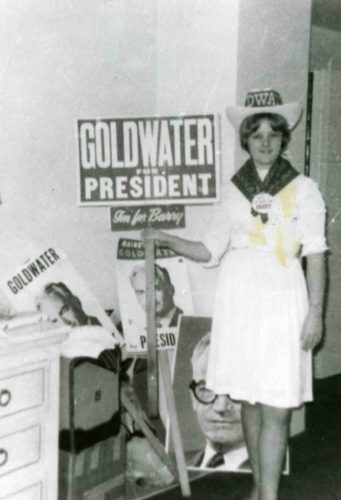

Swanee Hunt in 1964 during what she calls her Goldwater Girl years; her ultraconservative father supported Goldwater’s presidential campaign. Courtesy of Swanee Hunt

Her father was a distant parent, and while her mother, Ruth, was upbeat and nurturing, Hunt’s greatest sense of family came from First Baptist Church in Dallas. There, she spent hours at choir practice, Bible study and Sunday services. First Baptist introduced her to “Jesus, the social revolutionary,” Hunt later wrote in Half-Life of a Zealot. Through evangelical activities, she also met Mark Meeks, a minister-in-training who became her first husband. Hunt credits Meeks with opening her eyes to injustices — racial discrimination, poverty, the conflict in Vietnam — and finding in her Christian faith the motivation to fight them.

In college, where Hunt studied philosophy, she encountered ideas that would shape the rest of her life. For two years she attended Southern Methodist University in Dallas, where she read Man’s Search for Meaning, Viktor Frankl’s chronicle of his time in Auschwitz, a concentration camp in Nazi Germany-occupied Poland. Frankl’s thesis stood out for Hunt: “Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: The last of his freedoms — to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

She would return to Frankl’s ideas many times. As a young activist and philanthropist in Denver, she occasionally noticed contradictions between the missions of organizations she supported. But she decided to continue the sometimes messy work of local philanthropy, encouraged by Frankl’s assertion that a person should act even when every option is imperfect.

As a diplomat during the Balkan crisis in the 1990s, Hunt worried that the United States was doing too little to curb violence, even though intervening would have other geopolitical consequences. Frankl himself, an occasional guest at Hunt’s Vienna residence while she served as U.S. ambassador to Austria, reminded her that such decisions are never clear-cut and that courage lies in choosing action anyway.

In Rwanda, Hunt saw genocide survivors reclaim their agency by opting to forgive the perpetrators of violence, “choosing their own way” in the worst of circumstances.

Find a Truth

Hunt married Meeks when she was 20, and they moved to Fort Worth. While he attended the Baptist seminary, Hunt finished her degree in philosophy at TCU.

Philosophy professor Gus Ferre introduced Hunt to Soren Kierkegaard, who wrote: “What counts is to find a truth, which is true for me, to find that idea for which I will live and die.” Hunt wondered what hers was. In her parents’ conservative household, she had never been encouraged to make plans other than becoming a wife and mother.

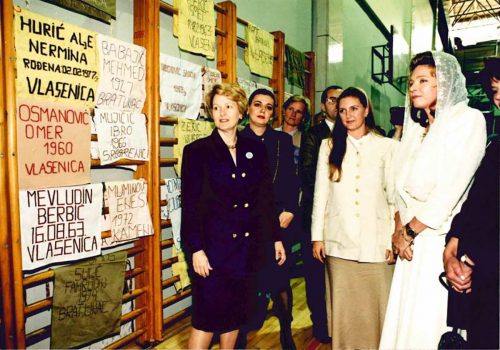

Swanee Hunt, left, with Queen Noor of Jordan, right, and other women in 1996 at the one-year commemoration of the Srebrenica Massacre in Bosnia. Women who lost a husband, father, son or other male relative in the massacre made the pieces in memory of the men killed. Courtesy of Swanee Hunt

Ferre was known for telling stories in class, and Hunt overheard another professor denigrating his habit. She defends Ferre’s approach. “He did tell lots of stories, but that’s how we learn — more than through academic rigor. Tell me the idea through a story.” It was a concept Hunt would return to years later, when she collected the stories of Bosnian and Rwandan women.

After graduating from college, Hunt and Meeks moved to Germany, where he pastored an American church and she earned a master’s in counseling psychology. The couple later moved to Denver, where Hunt earned a doctorate in theology. She and Meeks ran a group home for the mentally ill and volunteered for environmental and human-rights causes. Their daughter, Lillian, was born in 1982. Later the couple divorced.

Hunt’s exposure to disadvantaged people in Denver stood in stark contrast to her privileged upbringing. She grappled with how best to leverage her wealth to improve the world. Hunt and her sister Helen decided to start a private foundation benefiting marginalized communities in Denver, Dallas and Helen’s adopted city of New York.

The sisters called their foundation the Hunt Alternatives Fund, acknowledging their divergence from the rest of the family’s politics. In Denver, the fund awarded grants to women’s shelters, soup kitchens and programs for the mentally ill — direct services where Hunt could get to know providers and clients personally.

Starting a new chapter in her life, Swanee Hunt has moved to Washington, D.C., but continues her work in advocating for greater roles for women in the peace-building process around the world. Photo by Stephen Voss

The fund also created a nonprofit in Denver to help more than 70 organizations serving the mentally ill coordinate, rather than compete, in their funding requests. The cause was particularly significant to Hunt because one of her half-brothers was schizophrenic.

Fern Portnoy, a board member of the Hunt Alternatives Fund, said the foundation tended to support young organizations and ones that served communities of color. “At that time,” she said, “this was a departure from the practice of many other foundations in the community. In this sense, Swanee and Hunt Alternatives provided meaningful and lasting leadership.”

For Hunt, who had grown up in segregated Dallas, the approach was a natural response to injustices she’d witnessed as a child. Over time she realized that, just as she had been left out of decisions that affected her life as a woman, people of color were sometimes perceived by philanthropists as victims who needed the help of outsiders.

Hunt began to work alongside leaders from minority communities, particularly as she, Portnoy and several other philanthropists went on in 1987 to form the Women’s Foundation of Colorado, which supported nonprofits throughout the state that helped women and girls. The foundation’s first board members went on a listening tour of Colorado, asking women in urban and rural communities what they needed to solve local problems.

“Swanee always believed that the people most affected by problems should be the ones who help to develop the solutions,” Portnoy said.

Greater Reach

Hunt saw that grassroots work and grants had the power to improve lives, but in 1992, she began to focus on elected leaders’ ability to effect change on a grander scale. After meeting presidential candidate Bill Clinton at a fundraiser, she decided to invest in his campaign.

Humanitarian Swanee Hunt champions

women in the halls of power. Photo by Stephen Voss

“I realized that no other use of those dollars would go further to promote social justice,” Hunt later wrote in Half-Life of a Zealot. “With the stroke of a pen, any president of the United States could have an impact that people like me spent decades trying to accomplish.”

Clinton appointed Hunt ambassador to Austria. She moved to Vienna in 1993 with her second husband, orchestra conductor Charles Ansbacher; their son, Teddy, 6; and her daughter, Lillian, 11.

During Hunt’s tenure, Austria was still grappling with its role in World War II and the Holocaust. At a wreath-laying at the site of a concentration camp, officials repeated the words “never again.”

But to Austria’s south, the former Yugoslavia had disintegrated, and Serb leader Slobodan Milosevic was capitalizing on the instability. His campaign of ethnic cleansing killed more than 100,000 non-Serbs and drove 2 million from their homes.

With “never again” ringing in her ears, Hunt urged Clinton to intervene in the conflict and, afterward, to apprehend the war criminals. She worked to help the thousands of refugees who had streamed into Austria from the Balkan Peninsula, applying the knowledge she’d gained from her work with the homeless and mentally ill in Denver. In Vienna, she hosted negotiations between Croats and Bosniaks, two warring Balkan factions. All the political leaders and lawyers who attended those meetings were men. But on her dozen visits to Bosnia, Hunt met women who were putting the country back together in their own way. Women were creating jobs, educating the youth, caring for refugees and the elderly — the same type of grassroots work carried out by the organizations Hunt had supported in Denver.

The women she met in Bosnia told her how they had protested the violence and talked their sons out of joining armies; they didn’t want war because they saw the toll it took on their families and communities. Yet the international community’s focus was on negotiations among the male political leaders — sometimes the same ones who had initiated the conflict. Hunt realized the critical role women play in maintaining peace and the need to elevate their voices in conversations about security.

South Sudanese Cabinet member Rebecca Joshua Okwaci danced with Swanee Hunt at the JFK Forum at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government in 2012. As the founding director of the school’s Women and Public Policy Program, Hunt invited women leaders from around the globe to speak at the university. Courtesy of Swanee Hunt

As Hunt’s term as ambassador ended in 1997, she established an office of Hunt Alternatives in Sarajevo to support women and collect their stories for This Was Not Our War. She organized a conference called “Vital Voices: Women in Democracy,” where more than 300 women leaders from the U.S. and Europe exchanged ideas. Hunt also published an article about the status of women in Eastern Europe in the influential journal Foreign Affairs.

Back in the U.S. later that year, Hunt accepted an invitation from Joseph Nye, dean of Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government, to become the founding director of the school’s Women and Public Policy Program. She led the program for a decade and continues to teach a seminar focused on involving women in peace processes.

Women are often left out of the peace process because they are perceived as victims of war rather than leaders. It’s not uncommon, Hunt said, to hear a male official say something like, “When we get the country stabilized, then we’ll look at women’s issues.” No, Hunt would counter, getting the country stabilized is a women’s issue.

Women also are excluded because they typically do not rush to fill a power vacuum, Hunt said. They’re too busy raising children, caring for elders, tending crops or running markets, and women tend to gravitate toward positions of community activism rather than elected leadership. But research shows peace processes that involve women are more successful. Women in negotiating teams relate to the women across the table, Hunt said. Both sides are invested in stopping conflict before it kills their husbands and children.

Swanee Hunt spoke to a group at SMU about the Rwandan genocide and women’s accomplishments in a post-conflict society. Photo by Leo Wesson

Hunt wanted to connect women leaders from conflict areas with one another and with policymakers. She wanted to equip women with the skills to take their peace-building work to the national policymaking level. In 1999 she formed Women Waging Peace, now a worldwide network of 2,000 women including government officials, nongovernmental organization leaders, businesspeople and leaders in civil society. Members can be called upon to serve in peace processes and to share strategies for creating more enduring peace agreements and policies that address the needs of everyday people.

Hunt later added research and advocacy arms to the network and changed the project’s name to Inclusive Security. “In Washington, when you say ‘women,’ one eye glazes over,” Hunt quipped. “When you say ‘peace,’ the other eye glazes over. It sounds mushy to a lot of people that we wanted to convince.” But policymakers cared about “security,” and even if they had no idea what “inclusive” meant, it piqued their interest, Hunt said.

Groundbreaking Approach

When Rina Amiri returned to her native Afghanistan in 2001 after the fall of the Taliban, she drew on lessons from Inclusive Security as she supported women running for seats in the national convention that would determine her country’s transitional government.

Amiri had helped Hunt create her Harvard course on Inclusive Security and had worked with women from conflict zones around the world. “Suddenly I was in this context where we had to very quickly come up with strategies, and this wasn’t a trial — it was the real thing,” Amiri said.

Swanee Hunt with Palestinian leader Zahira Kamal, left, and Guatemalan scholar and activist Luz Mendez during a trip to the Middle East in 2003. Courtesy of Swanee Hunt

Amiri is now a visiting fellow at the Center on International Cooperation at New York University. She also serves as a mediation adviser with the United Nations, specializing in inclusive peace processes. She said Hunt’s approaches to involving women are now considered standard but were groundbreaking when Hunt began. “She was one of the leaders who took a nontraditional approach and opened up spaces for a lot of voices that wouldn’t otherwise be heard,” Amiri said. “She’s somebody who’s very entrepreneurial in spirit, and I find it’s one of her greatest assets.”

In the late 1990s, Hunt advocated for the adoption of U.N. Resolution 1325, which calls for the full involvement of women in conflict prevention and peace negotiation. The resolution was adopted by the Security Council in October 2000.

“Swanee has been instrumental in placing the importance of women in both peace building and security into the mainstream agenda of international relations,” said Victoria Budson, who helped create the Women and Public Policy Program at Harvard and currently serves as its executive director. “It’s made a difference that Swanee focused on this and dedicated her life to changing women’s ability to participate.”

Swanee Hunt at a 2014 symposium co-hosted by Inclusive Security on women, peace and security in Nairobi, Kenya. Courtesy of Swanee Hunt

The same year the resolution was adopted, Hunt began to travel to Rwanda, where women were helping rebuild the country after the 1994 genocide. She met President Paul Kagame, whom she urged to involve women in all levels of government.

Hunt and her colleagues established an Inclusive Security office in Kigali for two years and invited Rwandan women to the U.S. for training. The relationships she formed became the basis for Rwandan Women Rising.

Hearing about the unbearable trauma the women endured, Hunt thought back to Viktor Frankl. He concluded that, even in the worst circumstances, a person can still choose her response to the situation. “If the women, after a horrific, horrific genocide, can figure out how you put the country back together, that’s a magnificent story that should instruct us every day and every hour of our own lives,” Hunt said. “That’s what they did, and that’s the story I had to tell.”

Across the African continent, Hunt has helped amplify the stories of women in war-torn Liberia. In 2006, Hunt invited businesswomen and philanthropists, including Abigail Disney, to visit Liberia in support of newly inaugurated President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf and her female appointees.

While in Liberia, Disney learned about activist Leymah Gbowee and the demonstrations she had organized that helped end Liberia’s civil war. After the trip, Disney produced the 2008 documentary Pray the Devil Back to Hell, which tells Gbowee’s story. The documentary raised the profile of Gbowee, who, along with Sirleaf and Yemeni journalist and activist Tawakkol Karman, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2011.

Swanee Hunt visited women during a 2006 trip to Liberia. Hunt’s invitation to businesswomen and philanthropists was to support newly inaugurated President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf and her female appointees. Courtesy of Swanee Hunt

Disney went on to make more documentaries about women and social change and founded Peace Is Loud, a nonprofit that highlights the work of women peace builders.

“Swanee has been the first and loudest voice for the idea that women belong at the table, not as tokens and not because we should be nice to them, but for the idea that without them peace cannot be made,” Disney wrote in an email. “Through Harvard and all the other organizations she’s started or helped, she has managed to take an idea that on its face was received as absurd when she started and make it a necessary fact of diplomacy in the 21st century.”

The Next Right Thing

The next chapter of Hunt’s story takes place in Washington, D.C., where she moved in late 2017 after two decades in Cambridge, Massachusetts. On a warm October day, her new apartment echoed with the sounds of paintings being hung, boxes delivered, rugs unrolled. Barefoot, in leggings and a T-shirt that read “This is what a feminist looks like,” she supervised the team arranging furniture and artwork.

Hunt made the move alone. Her husband died in 2010, and her children are grown. Yet mementos throughout the apartment keep her loved ones close. The grandfather clock is the same one that chimed the hours outside her childhood bedroom. Sculptures in the hallway rest on pieces of her children’s furniture: Teddy’s old desk and Lillian’s chest of drawers. In a stack of theology books is her childhood Bible, its endpapers covered in Hunt’s earnest handwritten notes.

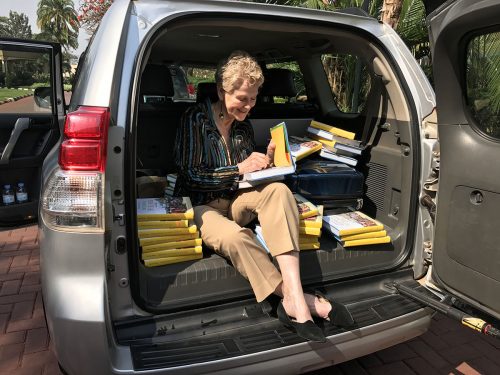

Swanee Hunt signing copies of her book Rwandan Women Rising in Rwanda in 2017. Courtesy of Swanee Hunt

She would have preferred to find Washington adapting to the first female president, her longtime friend Hillary Clinton. The morning after the 2016 election, Hunt woke up curled in a fetal position. Her phone was buzzing nonstop with distraught texts from employees and friends. Crushed, Hunt wondered what to say. She decided to respond to each text with six words: “Just do the next right thing.”

For Hunt, those words mean pressing lawmakers to elevate the role of women in war zones. She plans to bend their ears on Capitol Hill and contribute to publications read in the halls of power: The New York Times, The Washington Post, Politico, Foreign Affairs. At her expansive dining-room table, she will convene people from across the political spectrum for policy discussions over meals.

In October 2017, President Donald Trump signed the Women, Peace and Security Act. The federal law requires every part of the U.S. government involved in conflict prevention and resolution to promote meaningful participation by women.

The victory represented 18 years of effort for Hunt. She said that when she and her colleagues started their advocacy, passing the act seemed impossible. That didn’t matter. The idea that something is impossible does not fit in Hunt’s story.

“The notion of what’s possible or not is really useless,” Hunt said. “I think it’s a waste of time to try to figure out. You just say, ‘Here’s the need. We’re going to lean full force into it.’ The possible and the impossible — it’s just a mental construct.”

Swanee Hunt’s Books Highlight Humanitarian Efforts to Rebuild War-Torn Nations

Rwandan Women Rising

Foreword by Jimmy Carter

(Duke University Press, 2017)

Book cover art courtesy of Duke University Press

After a devastating genocide tore apart Rwanda in 1994, the country’s women carved out new roles as visionary pioneers to create stability and reconciliation. Today, 64 percent of the seats in Rwanda’s lower house of Parliament are held by women, a number unrivaled by any other nation. Swanee Hunt illustrates how the Rwandan women’s accomplishments provide important lessons for policymakers and activists who are working toward equality in other post-conflict societies.

Worlds Apart: Bosnian Lessons for Global Security

(Duke University Press, 2011)

As U.S. ambassador to Austria in the 1990s, Hunt was involved in American policy toward the Balkans. With a focus on the Bosnian War, Worlds Apart explores the implications of military intervention on humanitarian grounds. Sharing perspectives from people living amid the war and outsiders deciding whether or how to intervene, Hunt draws six lessons that can be applied to conflicts throughout the world to build a stronger paradigm of inclusive international security.

Half-Life of a Zealot

(Duke University Press, 2006)

Hunt’s autobiography traces her childhood in Texas to her life’s work in political, academic and humanitarian advocacy. Daughter of legendary oil magnate and ultraconservative H.L. Hunt, she developed a different outlook that inspired her to work for compassionate causes around the world.

This Was Not Our War: Bosnian Women Reclaiming the Peace

Foreword by William Jefferson Clinton

(Duke University Press, 2004)

In her first book, Hunt draws on seven years of interviews and her own experiences as a diplomat and humanitarian. The book includes first-person accounts of 26 Bosnian women who reconstructed their society after years of warfare. Representing various ethnic traditions, mixed heritages and economic classes, the women share their thoughts on the destruction and rebuilding of their country.

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related reading:

Features

TCU Educates the Next Generation of Rwandan Leaders

Rwandan students seeking ways to positively impact their country’s future turn to TCU.

Features

Crossing borders – TCU’s bond with Rwanda

As a child in Rwanda, Yannick Tona survived genocide to become a tireless promoter of tolerance and cross-cultural understanding.

Features

Warrior for Peace

Nobel laureate Leymah Gbowee mobilized women to demand an end to Liberia’s second civil war.