Real-life Faces of Education Reform

For Francyne Huckaby, filmmaking brings her academic research to life.

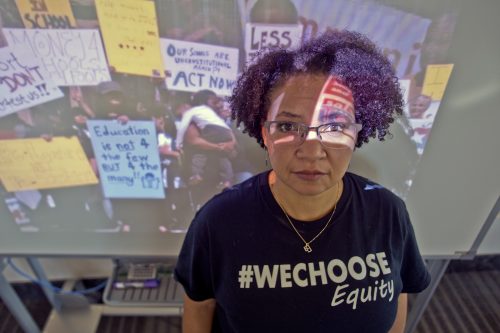

Professor Francyne Huckaby says filmmaking reconnects both filmmaker and audience to the oral tradition of storytelling. Photo by Mark Graham

Real-life Faces of Education Reform

For Francyne Huckaby, filmmaking brings her academic research to life.

On the evening of Sept. 9, 2012, the Chicago Teachers Union announced its members were striking for the first time in 25 years. M. Francyne Huckaby ’96 MEd, associate dean of the School of Interdisciplinary Studies and professor of curriculum studies in the College of Education, was there to speak with the teachers and community members who were struggling against the consequences of neoliberal school reform.

Neoliberalism, as economic geographer David Harvey asserts in A Brief History of Neoliberalism (Oxford University Press, 2005), is the view that competition and market forces should dictate every corner of public life. The doctrine has thrived since the early 1970s. School funding and teacher pay based on standardized test scores and the creation of charter schools and voucher systems in the name of freedom and parental choice are among the most talked-about neoliberal reform measures. But, Huckaby said, policies such as these have resulted in the marginalization and disempowerment of numerous communities and in schoolchildren being treated as if they are a market.

“The argument is prevalent that we need new types of schools — typically charter schools — which give parents choice,” Huckaby said. “But oftentimes the pot of money that supports the schools doesn’t become a bigger pot of money; it’s the same pot of money the state or municipality has allotted for education. So schools deemed to be underperforming are closed in order for the new schools to be created. This happens most frequently in poor communities and communities of color.”

A school closure often sends students scrambling. Some may be unable to attend the new one because of formal or informal barriers — admission to a charter school may be based on academic performance, or the student may lack transportation, for example. So those students seek nearby open-enrollment public schools, which quickly become overcrowded.

Francyne Huckaby, professor of education and associate dean of the School of Interdisciplinary Studies, incorporates filmmaking into her field research on education reform. Photo by Mark Graham

“The parents and students alike become upset,” Huckaby said. “Resources are strained, and now the overcrowded school begins to have difficulty meeting state standards and is also in danger of being closed.”

Huckaby’s 15 years of interdisciplinary scholarship resists simple description, but the crux of her research examines power relations specific to curriculum through ethnographic, postcolonial, feminist and sociological lenses. As with most scholars, Huckaby’s medium has long been prose, her finished work printed in academic journals and edited volumes. Beginning in 2012, however, she began to explore film as a means to gather and share her critical findings.

Huckaby spent time on the road in 2012 and 2013 listening to individuals and communities who were fighting school reform measures. In addition to Chicago, her research took her to Houston, Austin, New York City, Seattle, Washington, D.C., and Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Upon her return, she analyzed field notes and organized her thoughts, and she was eager to share her experiences with North Texas teachers and people in the community.

“But I found people didn’t believe what I was saying,” she said. “I was hearing a lot of, ‘But charter schools are good! They give people choice!’ One day I was with a group of educators, sharing about what I was seeing in Chicago, and I could barely get a statement in without having to deflect their counterarguments.”

During this particular discussion, Huckaby grew frustrated and decided to try something different. In addition to her notebook, she had taken an iPad on her trips to record video and images to review during the writing process.

“I had filmed public testimony at the U.S. Department of Education in Washington, D.C., and, tired of arguing, I just opened up my computer and pulled up the first video file I saw,” Huckaby said.

The footage — recorded from the back of a room at the U.S. Department of Education during a Journey for Justice Alliance public event — was raw and unedited. Nevertheless, Huckaby said, it triggered a seismic shift in the room and represented a watershed moment in her career as a critical qualitative researcher.

In the clip, a young man from New Orleans was explaining that as an honors student and a high school senior, he should be excited. Instead, ongoing segregation and the elimination of public, open-enrollment schools following Hurricane Katrina made him feel undeserving of an education.

Filmmaking, Huckaby said, reconnects both filmmaker and audience to the oral tradition of storytelling, capturing the temporality of a given moment or event and oftentimes providing an emotional experience for the viewer.

“Showing that clip completely changed the tone of the conversation. The people present were immediately interested, wanting to know, ‘Who is this kid?’ ‘Whom is he addressing?’ ‘Where was this meeting?’ ” Huckaby said. “Historically, the people who have personally experienced the harm of public school reform have understood my research. But those who hadn’t experienced it either didn’t believe what I was saying or they didn’t believe it could happen in their city. Filmmaking opened up possibilities for that to happen.”

In academia, the printed word remains a gold standard. Thus, Huckaby wrote about her experience as a filmmaker in “becoming cyborg: activist filmmaker, the living camera, participatory democracy, and their weaving.” Published in 2017 in the International Review of Qualitative Research, the paper argues that filmmaking has a place within critical qualitative analysis and traditional ethnographic and sociological scholarship. She details her experience holding a camera instead of pen and paper while embedded in the communities whose struggle she was attempting to illuminate.

Francyne Huckaby took several filmmaking courses at TCU to sharpen her skills. Photo by Mark Graham

“Her work is very innovative, and her films constitute very serious scholarship, adding not only to the body of knowledge here in the College of Education, but also to the field of education and qualitative research throughout the country,” said Jan Lacina, professor of literacy and associate dean of graduate studies in the College of Education. She said that Huckaby uses filmmaking as an innovative method for researchers to connect with participants as well as a powerful way to share research outcomes.

The paper’s title is a reference to the inseparability of researcher and camera. Huckaby knew that if she were to become cyborg and present her research via film, she wanted to do it well.

“I took a couple of filmmaking classes here at TCU, and, of course, I learned that everything I’d done is wrong,” she said. “I learned a lot from Andrew Haskett ’81 MS and Greg Mansur ’04 MFA, [associate professors of professional practice in film, television and digital media]. I asked them what sort of equipment to get and what I should be thinking of in terms of sound. I learned more about lighting and stabilization and what kind of shot is a good shot.”

After the publication of “becoming cyborg,” Huckaby edited Making Research Public in Troubled Times: Pedagogy, Activism and Critical Obligations (Myers Education Press, 2019). She also wrote Researching Resistance: Public Education After Neoliberalism (Myers Education Press, 2019), in which many of her short films are accessible to readers through printed QR codes.

Among its many functions, Huckaby’s research aims to close a distance between community needs and the needs of the researcher or institution.

“When she talks to community members, she is forging a genuine connection. She has a way of communicating that always makes people feel valued and never less-than.”

Jayna McQueen Baker, assistant principal at Kennedale High School near Fort Worth

“Mine is a type of research that is responsive to what is happening in the world, and in some ways it meets a need,” she said. “People have been doing research on education reform, and even producing films about it like Waiting for “Superman” or Won’t Back Down, but a lot of this work is intended to support charter schools and privatizing education. I have been studying the people who have been pushed to the margins by these policies and laws enacted under the auspices of progress and reform.”

Jayna McQueen Baker ’19 PhD said that whether Huckaby is advising her graduate students or traveling the country to witness communities in resistance, her posture is always one of humility and generosity, assuming a dignity about everyone she meets.

“She has a profoundly deep knowledge of curriculum theory and qualitative methodology, and she is a very well-respected scholar,” said Baker, who earned her doctorate in curriculum studies from TCU before becoming assistant principal at Kennedale High School near Fort Worth. “Yet, when she talks to community members, she is forging a genuine connection. She has a way of communicating that always makes people feel valued and never less-than.”

Without children of her own and as the product of a variety of educational environments — from public elementary school in Houston’s Third Ward, a master’s degree from TCU and to a PhD from Texas A&M University — Huckaby admitted that her life may look different from those of the parents, students and educators whose activism she is researching. Still, she feels an obligation to take up the fight.

“I believe the academy has a great responsibility to the public, to the people at the site of research,” Huckaby said. “Even though I’m not a public school teacher and I’m not a parent, I wouldn’t be where I am now if I hadn’t received a very good education from my city’s public schools. So, in that way, their struggle is also my struggle.”

Your comments are welcome

1 Comment

Thank you for this inspiring feature! Would love to know where Dr. Huckaby attended elementary school. Through fourth grade, I went to the school that served San Felipe Courts. No resources, inner city school, but incredible teachers.

Wishing Dr. Huckaby all the success in the world!

Related reading:

Features, Research + Discovery

Elva Orozco Mendoza Studies Juarez Femicide Protests

The assistant professor of political science discusses “maternal activism” in Latin America.

Alumni

James Chase Sanchez’s Documentary Airs on PBS

Documentary filmmaker and alumnus wins an award for Man on Fire.

Features

Katherine Spillar Fights for Feminism

Activist helps lead the charge for gender equality.