David Moessner, the A. A.Bradford Chair of Religion, specializes in the Gospel of Luke. Photo by Glen E. Ellman

Found in Translation

David Moessner uses his knowledge of ancient languages to illuminate meaning in the Bible.

David Moessner, the A. A. Bradford Chair of Religion, is in his 11th year of teaching at TCU. His translation of the Gospel of Luke is in the New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition of the Bible. He is working on a book about ancient Greek narrative as it relates to the Gospels.

David Moessner has worked on an updated translation of the Gospel of Luke. “If a person like myself likes languages,” he says, “it’s kind of exciting.” Photo by Glen E. Ellman

The professor brings a broad view to TCU, having studied at Princeton, Oxford and Basel University. He teaches Jesus and the Gospels, as well as courses in biblical interpretation and Greek.

How did you become passionate about theology?

I grew up in a Christian family, and that was just a way of life. It was as a Lutheran I grew up, and junior high up through high school they had Saturday morning instruction; they don’t do that much anymore. By virtue of being in the church, I just got to read the Bible.

When I was an undergrad at Princeton University, I took a religion course my freshman year, and I really loved it. A lot of my beliefs were shaken or challenged, but it didn’t scare me away; it really made me want more.

I come from a family of physicians; my three brothers are physicians. So, I was supposed to be one, too. I did both pre-med and religion. I actually got into med school, but I didn’t go.

I went on in religion because I love to learn Greek and Hebrew; I love to read the original languages. I like ancient history. I love the fact that you had to study the history of Israel, and the Hebrew Bible, and all the Greek empires, different periods or phases of Greek ascendancy, pre-Hellenistic and Hellenistic and then the Roman Empire. So, it was a combination of history and ancient texts of Biblical material that I had gotten used to as a kid and in college.

How did you grapple with your religious views being challenged?

I took a course on the history of theology, from Schleiermacher to Tillich. And I would say that course and then the philosophy of religion course — those two courses really challenged me because they made me see new perspectives. And they made me then question what I really thought, what I really believed.

I dropped some of what I thought were sort of nonnegotiable views of things, like the inerrancy of the Bible, although I was more of an infallibilist.

I still have a very high view of Scripture, but I’m not stuck in some of those categories that keep one away from understanding what different cultures experience. And that’s, of course, especially important these days. How do people from different regions of the world and different cultural backgrounds understand some of the things we take for granted?

“A lot of my beliefs were shaken or challenged, but it didn’t scare me away; it really made me want more.”

David Moessner

You know Hebrew as well as Greek; which other ancient languages have you learned and how do these relate to the study of theology?

Well, I took Syriac. And I took Aramaic. Some say Hebrew is a dialect of Aramaic; Aramaic and Hebrew are very close. The vocabulary is different — that’s where it gets tricky. The characters are the same. So, you think you know Hebrew, then you read an Aramaic word that looks like it’s the same, but it’s not necessarily.

Jesus would have been speaking primarily Aramaic; that was his mother tongue. And Hebrew, then, would be the language of the Scriptures. And the Gospels are written in Greek. If a person like myself likes languages, it’s kind of exciting.

Do you know any other modern languages?

I can speak German, especially when I’m there. I can read French, but I’m getting rusty in French, because I don’t read it as much as I should. I don’t know Spanish, which is my big problem. Wish I did. If I were young, I would learn Spanish for sure.

Now modern Greek is not the same as ancient Greek, or even the common Greek of the New Testament. But when I have been to Greece a couple times, there’s enough similarity that sometimes you can say, ‘Well, I know what that means.’ It’s the same text of characters, but it doesn’t mean the same as it used to mean. But that’s the nature of language, right? It’s constantly changing.

Do you have a favorite expression in any language?

I can give you a mantra that I think is my favorite because of the wisdom it contains: “To live is to love; to love is to know God.”

You were named a “premier scholar of the Lukan Writings” by the American Academy of Religion and Society of Biblical Literature in 2017. What drew you to the New Testament?

I had a course I took my freshman year, which was an introduction to the New Testament, and it was so good. It was a historical critical approach, which was basically new to me, but I really learned a lot. I was challenged in many ways, and I’ve changed views on many things. It made me more interested in studies of the New Testament.

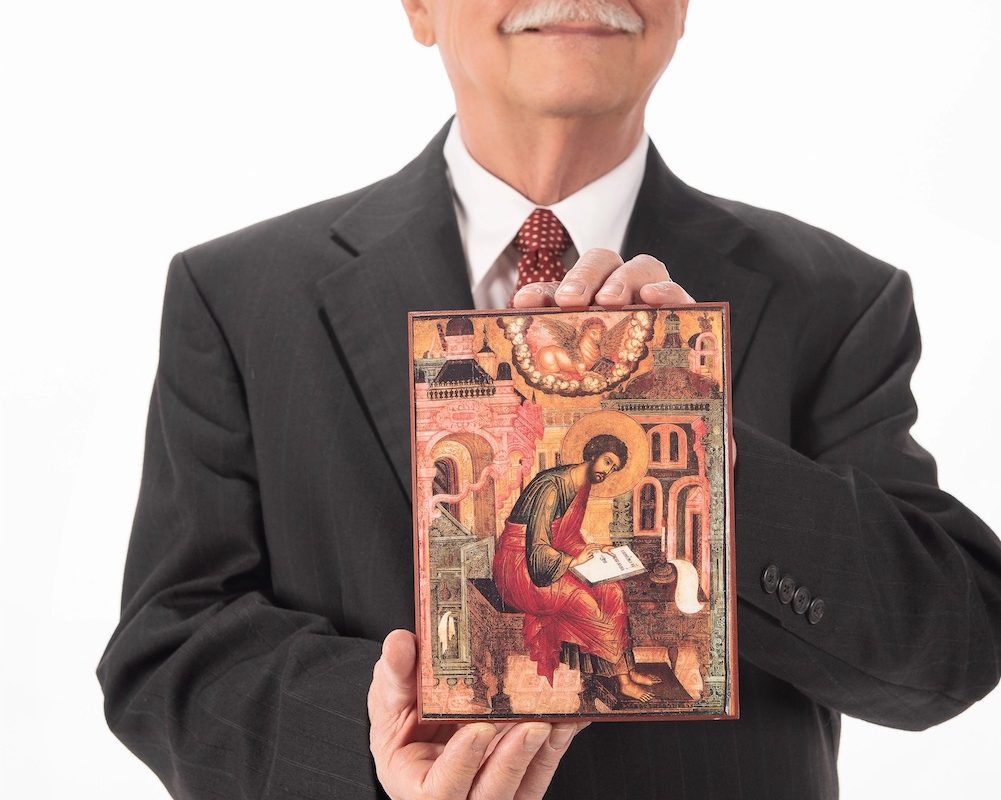

St. Luke writing the Gospel. Miniature painting from Book of Hours, ca. 1510. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

And when I was at Oxford, I got to see how important the Old Testament was for Christian interpretation. And then, part of the Oxford degree was the patristic period, early church writers. In those writings, we’re taking the person who Christ is, figuring and configuring Christ with the holy Old Testament. So it became very clear to me that I had to really study both testaments just to get a better view.

You are an ordained Presbyterian minister; do you act as a minister?

I’ve never had a church of my own, but I’ve always been active in the church. So, my wife and I — she’s ordained as well — we participate in the First Presbyterian Church in Dallas, because my wife teaches at SMU. Good ole rival. And she’s a professor at the Perkins School of Theology. She’s in practical theology, pastoral theology, counseling.

As a parishioner, are you ever seen as intimidating to the minister because of your knowledge in the field?

Fortunately, I get to know the senior ministers or the main preacher, and we strike up friendships. We started at First Presbyterian in downtown Dallas. They have The Stewpot ministry, and so the church appealed to us.

The first minister that we had there was a former student of mine, when I was in Atlanta. So I had the liberty with him to critique his sermon some Sundays. And he always was very respectful. And also, he was a superb preacher. And so we really got along — no going at each other.

What is compelling to you about the King James version of the Bible?

That was a monumental translation by a group of British scholars who were pulled together by King James. It’s the same kind of English in Shakespeare, and even to this day, I love the Psalms. When I was a kid, some of them I memorized, because it’s fantastic language. And the translators had what we would call today inferior Greek and Hebrew manuscripts available.

So, when you read the King James, the language was hard to understand at certain points; some of the idioms were no longer idioms that we understood. And separate words were also sometimes changed. Furniture in that period did not mean table. It meant the human body, what we call members of the physical body.

Do you have a favorite verse that comes to mind when you think of the poetic language in the King James?

“The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want.” What does “want” mean? Means I won’t lack for anything.

“He makes me lie down by green pastures. He leads me by the still waters. He restores my soul.”

“Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil.” Shadow of death?! Well, it makes sense from the Hebrew. It’s a dark place where death is all around. They could have said dark place of death, instead they said the shadow of death. It’s just that really fantastic English imagery.

Can you explain the significance of the New Revised Standard Version Bible released in 1989?

This is the only accepted English Bible by all Christian groups around the world. And one of the reasons for this is that it has what’s first called the Apocrypha by Jerome. Apocrypha means hidden text. It doesn’t mean bogus or untrue or mythical. When we say something’s apocryphal today, we mean it’s not true.

If you put all those books at the end, after the New Testament’s over, you make a clear statement: these are not really part of the Bible. As we know, Revelation is the end of the Bible, and it points to the end time and all that’s going on–imagery of the apocalypse and so forth.

“When you’ve studied the Bible all your life, even as a kid, you never think you’re going to be on a committee that would translate it, or re-translate it.”

David Moessner

What this Bible did in the New Revised Standard Version is it put the so-called apocryphal material, the Deuterocanonical text, right in the middle, right after the last of the Hebrew Bible. So, in a way, it brought Catholics and Orthodox together in a new way; they never shared the same Bible before.

What is meaningful to you about helping to translate the revised update of the Bible?

It’s a thrill for me — thrill of my life, actually. Because when you’ve studied the Bible all your life, even as a kid, you never think you’re going to be on a committee that would translate it, or re-translate it. And so, I took it with a lot of seriousness and solemnity, but also with a lot of joy.

The working thesis is “As literal as possible, as free as necessary.”

There is no word-for-word translation; that destroys translation. Word-for-word is not translation; it’s a misunderstanding how language works. All language is idiomatic; you try to give it a literal rendering, it just sounds goofy or it doesn’t make sense at all.

What does the process of translating this work look like? Which revisions are noteworthy?

I was asked, using the Greek text, to make suggested changes to this translation of Luke.

I ended up making quite a few changes. But there are only two or three substantive changes that I thought were important. One of the changes that I thought was really important was not accepted. Jesus refers to himself according to the Gospel texts as the son of man. Well, I suggested that it be changed to son of humankind.

The Gospel of Luke contains some of the church’s most used material, according to Moessner. This includes the Three Parables of the Lost: the lost son (the Prodigal Son), the lost coin, and the lost sheep. Photo by Mi Carmo via Pexels

It’s not because Jesus is a male that he’s called son of man, it’s because he is representative of all humanity. And rather than say, son of humans, or son of humanity, son of humankind has more of a rhythm to it. And the word “kind” in English represents the word in the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible in the Genesis story, “God created each according to their kind,” says NRSV and the King James. It was still rejected. It would upset too many people, probably.

The change that I was able to get through that I really liked is the opening of Luke’s Gospel. He says, “After investigating everything carefully.” That word in Greek was translated as investigate, but that’s not what the Greek word means. It came from a German rendering in the great lexicon or dictionary of New Testament and early Christian Greek.

[Luke] is one of those disciples who has been schooled in traditions and been trained in them from way back, that’s who he is. He’s not a historian who comes in and tries to write a new version based on history. [My translation] is going to be “as one who has grasped everything from the start”– that’s not exactly the way I said it but it’s close enough. That changes the whole relationship of Luke to the eyewitness tradition.

Much of the first two chapters of Luke are poems, Greek Old Testament meter and poetry. Well, I did that for the English.

Would you consider Luke’s to be one of the more important Gospels?

Oh, yeah. Of course, I’m biased. Luke has some of the most loved material in terms of the church’s use. The Good Samaritan parable, for example. The woman who keeps hounding the judge to get justice accomplished–that’s in Luke 17. You’ve got probably the most famous of all, the Prodigal Son, Luke 15. The Three Parables of the Lost. Only Luke has those three together; it ties the lost sheep with the lost coin with the lost son.

And of the three writers, he is the most eloquent. He wasn’t a top litterateur, in the sense of the classical Greek writers. He wasn’t a Plato, by any stretch, but he was very good. And of the New Testament writers, he has the best knowledge of Greek and the best writing in Greek.

Editor’s Note: The questions and answers have been edited for length and clarity.

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related reading:

Features

Building Interfaith Bridges

By keeping the faith dialogue open and respectful, TCU prepares students for a religiously diverse world.

Alumni, Features

Duane Bidwell and the Complexity of an Interreligious World

Through his teaching and writing, the professor at Claremont School of Theology affirms the fluidity of religion.