Photo by Getty Images | BUSAKORN PONGPARNIT

Faculty Find Human Trafficking Through Massage Parlors

Two researchers are following the trail of demand that leads to smuggled and exploited people.

To the passerby, they appear harmless — storefronts offering massages to the stressed and weary, nestled in busy shopping centers anchored by well-known chains. But the grim fact is that many such businesses are part of the sprawling underworld of sex trafficking.

In the U.S., illicit massage businesses play an integral role in this $2.5 billion gray market, reports the Polaris Project, a nonprofit that fights human trafficking.

“Gray market refers to legal business entities where illegal activities may be occurring. It’s not quite black market but certainly isn’t white market either,” said Vanessa Bouché, associate professor of political science, who studies human trafficking.

While human trafficking happens in other industries, especially hospitality and agriculture, massage businesses in particular provide an ideal cover for sex traffickers. Even though they operate virtually everywhere throughout the U.S., these businesses remain understudied, Bouché said. “Most of these massage businesses are nodes within larger, organized criminal networks. … The vast majority of Americans have no idea it’s going on right under their noses.”

Vanessa Bouché, associate professor of political science, and Sean Crotty, assistant professor of geography, teamed up for a series of studies to provide new understanding on businesses that operate in partial or full illegality. Photo by Mark Graham

Leveraging an interdisciplinary approach, Bouché teamed up with Sean Crotty, assistant professor of geography, whose expertise is mapping informal and illegal economic activity. Together they have published two research papers since fall 2017 focused on massage businesses in Houston.

Crotty, who specializes in the relationship between economy and place, said, “Ultimately, one of the long-term questions we want to look at is: Are there differences or variances between law enforcement jurisdiction or customer demand that we can actually see playing out spatially, geographically?”

Visualizing these details on a map could help law enforcement better combat sex-trafficking networks.

Plausible Deniability

Even if law enforcement officers raid one of these businesses, they often have difficulty exposing traffickers and their accessories.

“Many of these businesses are structured such that the workers are not actual employees of the business. They’re contractors,” Bouché said. “If a woman forced to work in an illicit massage business is caught in a sex act by an undercover officer and they get arrested, the owner of the business claims plausible deniability: ‘Well, that woman is a contractor. We only gave her the space to work here. We don’t know what she’s actually doing in those rooms.’ ”

There is no traditional zoning in Houston, which means questionable massage businesses appear in unexpected locations.

Houston provides an intriguing test for Bouché and Crotty’s research methodologies. There is no traditional zoning in Houston, which means questionable massage businesses appear in unexpected locations. As a port city providing easy access to the cross-country Interstate 10 corridor, Houston is an attractive hub for smuggling and trafficking — two different crimes, Bouché said.

“Human trafficking, whether for labor or sex, is a crime against an individual,” she said. “Sometimes smuggling cases turn into human trafficking cases. … A human trafficking victim may believe she is only being smuggled across a border, but then once she arrives, the smuggler is working with a trafficker, and she is being coerced through emotional or physical abuse or debt bondage into some type of labor or sex.”

In illicit massage businesses, most trafficking victims are adult women from Southeast and East Asia, Bouché said.

“They’re told they’re going to be working in a massage business but not always told that they’re going to be engaging in sex acts — oral sex being the most common,” she said. “They are told that if they come to the U.S., their flights and visas will be paid for … and so they don’t have to worry about that. But once they arrive, they’re not paid a fair wage until they pay off their debt, which is often associated with some exorbitant interest rate.”

Mapping the Market

Houston is an international city and the fourth most populous in the nation, so it provides an enormous market for these businesses. In their article “Estimating Demand for Illicit Massage Businesses in Houston, Texas” in the September 2017 issue of the Journal of Human Trafficking, Bouché and Crotty counted 2,869 daily customers visiting illicit massage businesses citywide, yielding annual gross revenue of $107 million.

Making use of video recordings taken from the illicit massage businesses in the study sample, the researchers were able to count the number of people entering the establishments, Bouché said. “And then there are the online review boards.”

Unlikely as it would seem, these massage businesses are named, rated and reviewed like any other business on public websites. While these websites are of little legal use to law enforcement, they do aid Bouché and Crotty in their analyses.

“We can discern a lot about each individual business based on these review sites,” Bouché said. “They allow us to look at the number of customers who provide reviews, average star ratings and the average amount customers are paying, as well as the types of payment accepted.”

The same user reviews helped Bouché and Crotty identify the locations of illicit massage businesses for their second paper, “The Red-Light Network: Exploring the Locational Strategies of Illicit Massage Businesses in Houston, Texas,” published in Papers in Applied Geography in 2018. After creating maps, the duo analyzed the geographic and spatial characteristics correlating with the success of these businesses.

Crotty and Bouché said Houston is just the entry point for their research, and they intend to investigate demand for these massage businesses in more U.S. cities.

“It will be really interesting to see the differences among cities in terms of locations of these businesses, their customers and what this information means for each city in terms of enforcement priorities, possible interventions and a variety of other policy focuses,” Crotty said.

“For illicit massage businesses, from a purely economic standpoint, our research represents something new. By these methods, we can really begin to understand demand.”

Sean Crotty

“This is the first example of actually being able to map consumer demand for services in this particular economy. Even traditional crime mapping is actually not very good at demonstrating demand for, say, controlled substances, drugs, because the only data you have access to is arrests, which speaks more to enforcement and not consumer demand,” he said. “For illicit massage businesses, from a purely economic standpoint, our research represents something new. By these methods, we can really begin to understand demand.”

The researchers said they hope that their work will raise public awareness about human trafficking and underscore the urgent need for changes to state and federal legislation and for task force-type strategies involving federal, state and community collaboration.

An Enforcement Quandary

In July 2018, Bouché spoke at a Colleyville Chamber of Commerce luncheon aimed at educating members about human trafficking within their city, a Dallas-Fort Worth suburb and Bouché’s hometown.

“The research [Bouché] shared was eye-opening,” said Colleyville Police Chief Michael Miller. “Until then, I hadn’t seen any empirical research indicating that these illicit massage businesses were one of the main mechanisms for sex trafficking. She could point them out to me on a map.”

Shutting down a Colleyville massage business would not eradicate sex trafficking in the city, Miller said. The real fight would be taking on a sophisticated organized crime syndicate.

Through presentations and panel discussions, Vanessa Bouché and Sean Crotty aim to educate groups about human trafficking in their own communities. Photo by Mark Graham

“If sex trafficking is cancer, then closing one or even all of the massage businesses involved here in Colleyville, where my jurisdiction lies, is only treating the fever,” Miller said. “Local police forces are set up to respond to emergencies in progress, to respond to crimes either in progress or reported after the fact. And all of our resources are tied up in seeing to these priorities.”

Trafficking networks use jurisdictional boundaries to their advantage, Miller said, so treating the cancer instead of the fever would require involvement by the federal intelligence community.

“I don’t have a single crime analyst, which is the kind of resource you need to understand all the players in these networks, how the money moves around and so forth,” said Miller, whose résumé includes work for the FBI. “It would require federal jurisdiction to take a holistic look at this.”

Bouché has consulted with the U.S. State Department and the National Association of Attorneys General to provide insight into the illicit industry and the need for greater regulation. The businesses often operate as anonymous shell companies — legal businesses established to mask ownership of assets. These shell companies provide a means of laundering the enormous amounts of revenue from commercial sexual exploitation.

“We’re trying to get 30 attorneys general on board to say, ‘Yes, we need better legislation surrounding the anonymous shell companies.’ This would greatly impact the industry,” Bouché said. “I also have consulted with the U.S. Department of State’s Diplomatic Security division.”

Looking to future projects, Bouché and Crotty face a significant research challenge in the darkness of the subject matter.

“Really, across all human trafficking research, it’s all just so wholly depressing,” Crotty said. “You sort of have to force yourself to take breaks — go play with the dog and just check out for a little bit.”

Bouché, too, said she must disengage from the grim statistics, the maps and her computer screen. She turns to yoga, knitting and crocheting for relief.

“I wanted to stop doing the work for a time. But I just can’t,” she said. “I look at my friends who are survivors of human trafficking and my friends who are on the front lines serving victims, and I remember that the work is too important.

“The resiliency of the human spirit is greater than the evil that seeks to quash it. When you surround yourself with the right people — others who are as ambitious for justice as you are — you remember that you just have to keep going. I won’t stop doing the work.”

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related reading:

Campus News: Alma Matters

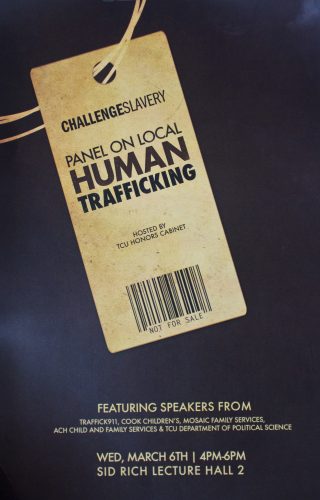

Fighting Human Trafficking

Research shows more comprehensive – not harsher – legislation curbs human trafficking.

Features

Peace for the Next Generation

Jaime Horn ’98 trains female negotiators.

Features

Computer Science Students Design Apps in Class

Capstone projects give teams chance to use software design skills to help clients improve services.