Jim Wright Journals Offer Inside View of Political Life

In diaries left to TCU, the congressman talks politics and power.

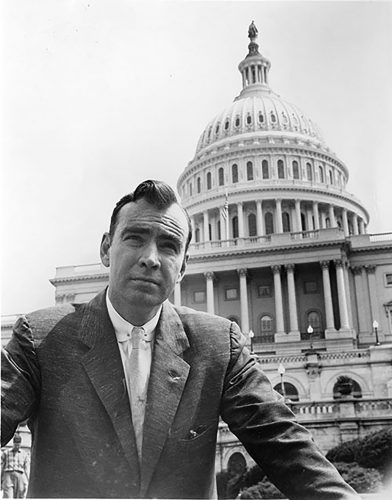

Jim Wright begins his journal the way many people do, with a bit of personal stock-taking of where he was in life. Like musing on whether he will become president of the United States.

It’s December 1971, and Wright, at 50, is beginning his 18th year representing North Texas in Congress. He is five years away from becoming majority leader, 16 from becoming speaker of the U.S. House. He’s ambitious, a workaholic deeply knowledgeable about legislative and political battles, a top-notch orator, somewhat temperamental. Wright is a dreamer with a large, fragile ego, someone who wants to make a difference. He will write prayers into his journals.

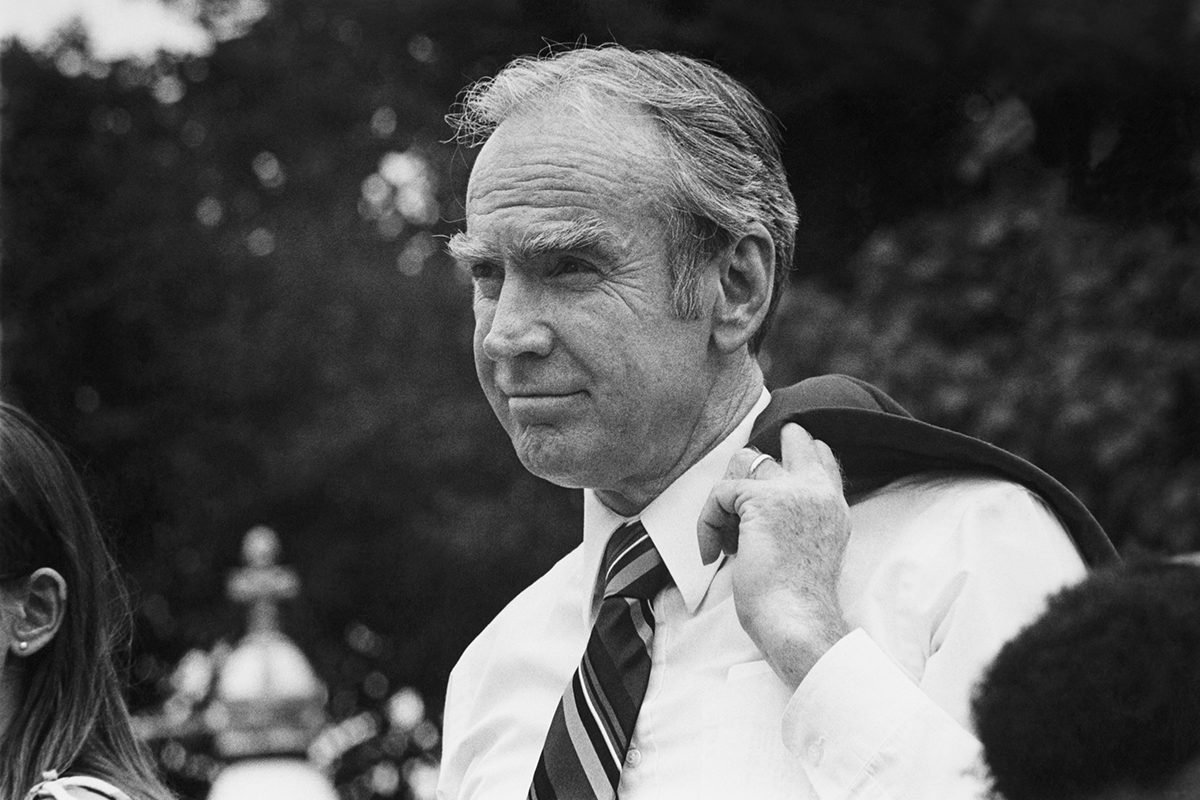

In a journal entry from Dec. 30, 1971, Wright bemoans his financial situation. Photo by Mark Graham

Such a successful person, still on his way to even more powerful roles, might be inclined to make rosy predictions. Instead, the veteran politician and Fort Worth native admits that the fires of ambition have begun to burn lower.

“Maybe just in the past year have I really acknowledged that I won’t ever be President,” he writes. It sounds almost like revealing something shameful. In one sentence, he has let readers in on the breadth and limits of his ambition. Succeeding paragraphs offer tantalizingly intimate glimpses into what drives him.

The congressman’s father once told him that he could be anything he wanted “if only I wanted to do it strongly enough.” Wright agrees, adding one stipulation — only if he is willing to pay the price.

“I’m no longer willing to pay the price … for escalation up the political ladder,” he writes. “I’m not willing to humble myself, to go hat in hand to the fat cats and beg for money.”

In fact, “my finances are in shambles,” he writes, and he admits his fear that he may never pay off his debts. He’s worried about what the press is saying; the news coverage is so often a bitter brew he must swallow with breakfast.

That rambling first entry on Dec. 30 serves as a template for a series of journals that hopscotch over the next 20 years and in some ways foreshadow what happened in Wright’s career.

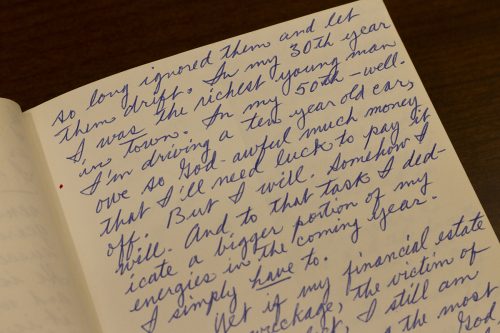

The diaries span about a linear foot of shelving in the Mary Couts Burnett Library’s Special Collections space for the Jim Wright Papers. Some are thick, specially made volumes given to him by friends, while others are the kind of one-year diaries available in any school-supply aisle.

Some of Wright’s personal journals are bound together as books. Photo by Mark Graham

Wright’s excellent handwriting fills page after page. The writing becomes more spidery in later years, but the sentences are still clear and often eloquent. They are first drafts with seldom a scratched-out word or grammatical lapse.

The journals in the TCU collection end in 1991, a couple of years after Wright resigned the speakership and his seat in Congress, rather than drag himself and the U.S. House through a full deliberation on charges that he violated ethics rules over sales of a book and the hiring of his wife by a Fort Worth supporter.

The volumes in many ways carry out the highly personal tone set by those first few entries. He writes about occasional disagreements with his second wife, Betty; about the pleasures of spending an afternoon gardening; about regrets over speaking too sharply and hurting someone’s feelings. Long pages describe the details of key legislative issues and how particular votes went down. In an unintentionally hilarious passage, he reports his offer to spar a few rounds — Wright was a boxer in his youth — with a top-rated fighter.

In other ways, the journals are maddening in what they leave out.

The volume for 1971 to 1978, for instance, skips three years, including the critical year when he won the majority leader post by a single vote in a hard-fought battle. There are no journals in the collection covering his time as speaker or the uproar that drove him to resign.

Author and historian John M. Barry followed Wright to meetings and other activities for months while he gathered information for his 1989 book The Ambition and the Power: A True Story of Washington (Viking). He remembers reading some of the journals back then, and he’s not surprised by their combination of seeming openness and missing details.

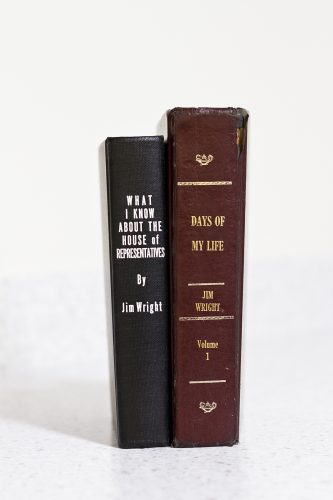

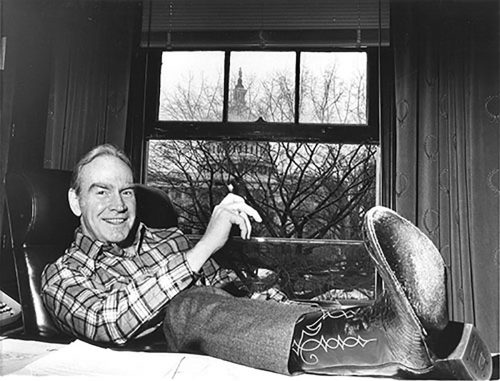

Jim Wright in Washington. Courtesy of the Mary Couts Burnett Library’s Special Collections

“He revealed only a tiny part of what he knew was going on,” Barry recalled. “He was aware he was writing for the record.” Because of that, he said, the journals are “not truly confessional.”

Something similar happened when Barry was gathering information for his book about Wright. The speaker gave him “unbelievable access,” he said.

When Barry asked Wright questions in informal settings, maybe just walking down a hall at the U.S. Capitol, he got candid responses. But when he sat the speaker down for a formal interview, the material was “useless,” Barry said. “We might as well have been on Meet the Press. He left out so much, which was ironic because he knew I knew.” Barry had been in the meetings, heard the arguments and knew the aspects that Wright was glossing over.

James Riddlesperger, professor of political science at TCU, agreed that Wright knew he was “writing for posterity” in the journals. Riddlesperger worked with Wright on a collection of his writings and speeches, The Wright Stuff: Reflections on People and Politics (TCU Press, 2013).

Wright “led a very, very public life. He was writing from the heart, but scripted, too,” Riddlesperger said. He described the portions of the journals he has read as “incredibly articulate. He gave his thoughts in complete sentences” and in beautiful script.

Wright, who “lived his whole life pre-computer,” didn’t type but took pride in his handwriting, Riddlesperger said.

Like most journals, Wright’s are, in retrospect, more revealing than the writer had probably intended. Especially the last in the series: At a psychiatrist friend’s suggestion, Wright devoted that 1990-1991 volume to his worries and his dreams. He reports on both topics meticulously, as though this were now his job.

What does he dream of? Essentially, the same things he wrote about in 1971. His anguish about press coverage and about where Congress and the country were headed on various issues. In his dreams, he is often performing some major public service. The demons of debt and money are always present. And there’s one new topic he can’t leave alone: whether his reputation will ever recover.

A dream “in which I was directing the transition from wartime to peacetime economy, hiring a staff, and also writing a book about it.”

July 2, 1991

Reading Wright’s journals is not a relaxing exercise. Just hearing the details of his congressional schedule — or the topics of his dreams — is wearing. Many of the entries from his congressional years were written while he was on a plane, going home to Fort Worth for the weekend, crisscrossing the country to support colleagues in their re-election campaigns, or traveling on breaks with other members of Congress to different parts of the world to meet with leaders and legislators.

On a typical weekend in Fort Worth in 1971, he made speeches at four public appearances, including one in Spanish, and he reports getting a standing ovation each time. He complains about the grueling workload, but adds, “I asked for this job and I’m glad to have it.” And, a few days later, “The story of my life is written in answered prayers.”

Answered prayers and sustained success as a public officeholder don’t seem to be enough for Wright, however. He needs constant reassurance that people like and respect him, a conundrum he recognizes as a failing.

In one incident, Wright recounts having gotten plenty of praise and applause following a speech to about 500 people. Just one night later, another orator’s similar success before a different crowd sends him into a fit of jealousy, in part because of a slight from a decade earlier. Betty talks to him about what Wright acknowledges is his “seemingly insatiable desire for public appreciation.”

No one but Betty knew he was jealous of the other orator, he writes. “She sensed my mood, as she always can.” Later that night, “Betty put it very plainly. She said, ‘Jim, can you not be happy unless you’re the center of attention every night?’ ” The arrow, he wrote, “hit its mark.”

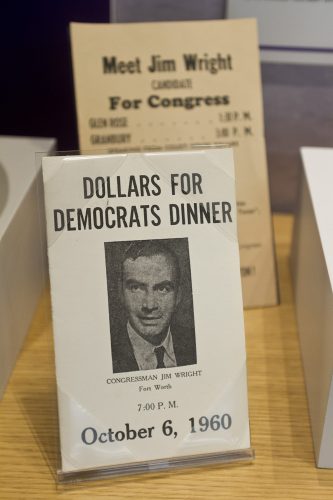

Event memorabilia from the Jim Wright Collection is on a rotating display in the Mary Couts Burnett Library. Photo by Mark Graham

By 1986, when he is majority leader in the U.S. House, Wright’s workload and worry-load have increased exponentially. He is deeply involved in the details of major legislation.

In just two days of diary entries in February of that year, he describes progress on a budget reconciliation bill, a trade bill and a package of anti-terrorism measures, ticking off parts of the terrorism package that will have to come from each committee and describing the committee chairs’ positions and personality quirks.

At least one powerful committee leader is not giving the reconciliation measure the priority Wright thinks it deserves. “If and when I’m speaker, maybe he will,” he says.

The next day Wright and colleagues meet with network TV executives who tell them the Democrats need to do a better job of on-air responses to President Ronald Reagan’s speeches. Wright will take on that job shortly thereafter.

A couple of days later, after a dinner with the former chancellor of Germany and a former British prime minister, Wright goes on for several pages about their policy-oriented discussions. Both men are critical of Reagan, regarded as a dangerous “cowboy” by many in Europe.

“[C]learly both feel our system of choosing a president without any previous national or international experience is fraught with increasing danger,” Wright writes, a comment on Feb. 24, 1986, that seems applicable to today’s political realities.

After a lunch at a “modest old farmhouse” on a friend’s North Texas ranch: “There is something reminiscent of an earlier country era in the ease of the welcome and sharing of what there is, with neither pretense nor apology.”

Jan. 8, 1978

In Washington, most of Wright’s social occasions seem to be work-related — meet-and-greets with fellow Democrats or with one group or another. An afternoon off for gardening is a guilty pleasure.

Although his career in Congress feeds both his ego and a deep desire to serve his country, Wright only seems truly at ease with the regular folks outside the marble corridors of political power, whether it’s back home in Texas, on congressional trips abroad or even in a relative’s florist shop in Brooklyn. A child of the Depression, he is clearly uncomfortable with the pompous, the self-aggrandizing, the elite.

Jim Wright stayed true to his Texas roots throughout his time in public office. Courtesy of the Mary Couts Burnett Library’s Special Collections

Wright was a politician in the old style, Riddlesperger said, where “pork” translated to bringing jobs to his district. “He was a very calculating politician. But he always had the bigger picture in mind as a public servant, and his journals reek of that,” the professor said. “He saw himself as someone trying to make sure his constituents and the common people got a fair shake.”

In a section from January 1972, several pages in the diary seethe with Wright’s anger over the refusal by a group of Fort Worth anesthesiologists to treat an 8-year-old girl because of disagreements with her plastic surgeon, who is Hispanic.

“My capacity for indignation, for outrage, in fact, has not yet disappeared,” Wright writes. “Because of their smug petulance, a little eight-year-old girl, suffering from painful burns all over her body, was denied the [anesthesiology services] necessary for emergency surgery.” In the end, the little girl had to be transferred to another hospital, prolonging her agony.

“I’m going to get to the bottom of this one. Heads are going to roll, if I can make them roll!” he writes, complaining that physicians acting together can be “the most selfish group in our society.”

The day after a pleasant lunch at a North Texas farmhouse, Wright traveled to New Orleans to speak to a forum of “conservative but open-minded” business leaders. His remarks drew only one hostile question, Wright reports, from a “fat-cat independent oilman” who blasted Congress for trying to find a compromise on an important energy bill.

“What arrogance! As though being an oilman and rich automatically qualifies him as a spokesman for the south or for New Orleans or maybe for the nation. I let him have it, something I usually don’t do … probably too bluntly,” he writes. “But at the end I got a prolonged ovation. … What is it about so many oilmen that irritates me? Their presumption, I think.”

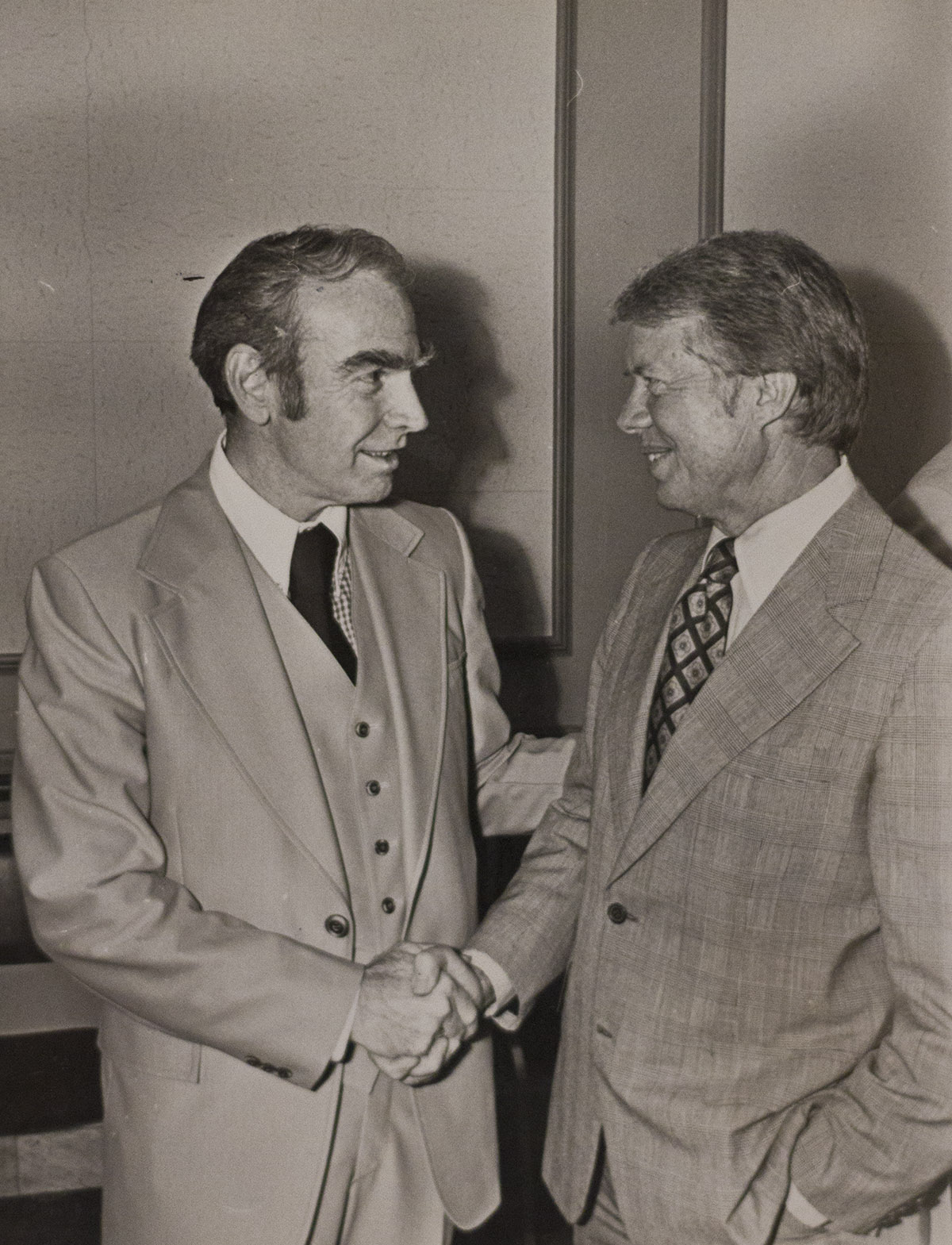

Jim Wright’s national political career spanned eight presidencies. Courtesy of the Mary Couts Burnett Library’s Special Collections

For several years in the late 1970s, Jim and Betty Wright spent their Christmases with Betty’s cousin Carol and her husband, Plato, a florist in Brooklyn. The few days leading up to Christmas were Plato’s busiest of the year, and the House majority leader worked with him in the shop.

Wright admired Plato’s work ethic; he liked talking to the “polyglot” folks who came into the shop, learned the names of the clerks at the nearby drugstore and went on deliveries, even to poor neighborhoods in Bedford-Stuyvesant, with Plato’s driver. When the druggist warned him that Bed-Stuy was dangerous, Wright scoffed.

“Whenever I have to be afraid to walk peacefully in any neighborhood in America, it’ll be time to quit! That time has not come yet,” he writes.

“In my 30th year, I was the richest young man in town. In my 50th — well, I’m driving a 10-year-old car, owe so God-awful much money that I’ll need luck to pay it off. But I will. Somehow I will.”

Dec. 30, 1971

Bumper stickers and a Democratic Party donkey figurine are among the memorabilia with Wright’s papers in the Mary Couts Burnett Library’s Special Collections at TCU. Photo by Mark Graham

If Wright was thinking of posterity when he wrote his journal entries, it wasn’t with an eye toward making himself seem a hero who does no wrong. The aches and pains along the way, embarrassment at his mistakes and anger at his own failings get plenty of ink in the volumes.

But it was in writing about money that he most put himself among the regular folks whose company he preferred. It was the problem that dogged him throughout the years covered by the journals and, in the end, helped bring about his downfall. It’s not a drive to be rich again, but just to make his and Betty’s lives a little easier, to pay off a mortgage, add a room to the house.

Through the years, Wright makes progress, to the point where he breathes a sigh of relief about paying off old loans. But in the last book of dreams and worries, it’s back again.

Money “was one of the big things of his public life,” Riddlesperger said, but to paint Wright as greedy (as happened during the controversy that ended his political career) “simply misrepresents who he was.”

Once in the late 1980s, Riddlesperger recalled, Wright came to pick him up at TCU “in a 1970s car with the roof falling in. I had to hold up the headliner.”

Wright’s wardrobe while in office “was famously off the rack,” Riddlesperger said. “The joke was, he wore the finest sports coat you could buy at J.C. Penney — in Washington, where tailored suits were expected.”

“We had a fine victory yesterday.”

Nov. 5, 1986

U.S. Speaker of the House Jim Wright met civil rights pioneer Rosa Parks at an event in 1988. Courtesy of the Mary Couts Burnett Library’s Special Collections

The middle years in the 20-year run of off-and-on journaling include much detailed discussion of political issues, including those Wright was proud of and others that frustrated him.

Wright worked as House majority leader during both the Carter and Reagan presidencies, and by the end, he was looking forward to becoming speaker of the House. He clearly intended to be a speaker who could get things done, someone who would lead the House in opposing many of Reagan’s policies.

“Everywhere Reagan went asking for a referendum on his policies, the voters elected the Democrat,” he writes in November 1986, referring to the midterm elections just before he became speaker. “I won by 69 percent and we gained the Senate along with some modest gains in House numbers. … A good and successful day in all.”

It’s the last diary entry before he becomes speaker. There are no more journals in the TCU collection until the last volume, which he begins in 1990, about a year after he has resigned the speaker’s job and left Congress.

The last volume of Wright’s journals in the TCU collection begins when he is still in turmoil over the ethics investigation that eventually leads to his resignation. The psychiatrist friend’s suggestion to write about his dreams and worries is an appropriate one: The worries — about saving his reputation and his legacy, about money — wake him in the middle of the night, and he writes down the dreams that are still fresh. He calls 4 a.m. “the worrying hour.”

A frustrating dream about “trying to remember where I left two suits.” He goes back to his hotel suite, only to find it “occupied by strangers.”

June 25, 1991

The dreams are sometimes eerily apt. Someone is removing his luggage early from a hotel, against his will. He argues with someone over paying a bill. He is back in Washington arguing politics, wandering a city that now seems foreign to him, reading unfavorable news stories, trying to figure out spurious charges on a credit card.

There’s an elaborate dream of putting together a “high-level global plan” and promoting it to Congress, and another about trying to scrape the crud out of the bottom of a bathtub.

The bad reputation that he earned because of the ethics investigation — spurred on by Newt Gingrich, a Republican who would later become speaker and suffer similar ethical problems — sometimes felt like the ruination of Wright’s life’s work, Riddlesperger said.

“It just killed him. He said to me, in a very self-revelatory way, ‘What is going to be my legacy?’ I can imagine that it led to the notion of free-falling” as described in the dream, Riddlesperger said. “But in the bigger scheme of things, he had an abiding trust that the system would be fair, would come down and place him correctly,” recognizing that his motives were good.

Ginger McGuire, one of Wright’s three daughters, said her father eventually made a kind of peace with what had happened to him.

“Dreamed of free-falling through the sky … coming to rest at a pleasant place …”

Aug. 9, 1991

In a letter, a copy of which was found in his archives, Wright wrote to Gingrich around the time the younger man became speaker. Wright tells him, in essence, that he thinks Gingrich owes him an apology. Many months later, he got a note back saying Gingrich would cease making derogatory comments about him and his family.

“I think that was closure for him,” McGuire said. “He closed that chapter and moved on” to a new career teaching at TCU.

No Texas politician’s wardrobe was complete without a Stetson, including this one with Wright’s papers at TCU. Photo by Mark Graham

McGuire has been doing research in the journals and the rest of the extensive collection of her father’s papers at TCU in preparation for writing a screenplay about part of his career, including his fight over the ethics charges and the major role he played in Latin American peacemaking while he was speaker — what he saw as an important part of his legacy.

She and others have looked in vain for additional volumes of Wright’s journals, as did his executor and the TCU librarians who have been cataloging and preserving the archives.

McGuire said she and her father talked about the idea of a screenplay before his death in 2015. “He was truly part of that generation that wanted to serve, to make the world a better place,” she said, and she wants his part in that process to be better understood by the public.

In the journal entry in which Wright recalls his dream of free-falling and landing safely, he also imagines creating a complex mural of photography, poetry and other media. In the dream, he writes, he was “unsure how [the] public will react, but I like it and [am] confident some others will.”

Your comments are welcome

2 Comments

I remember wearing a jacket down there in that cold archive where Mr. Wright’s donation was kept. Great memories cataloging his files while seemingly always having the sniffles. What an honor looking back.

Thanks for the memories, Gayle!

Related reading:

Features

Towering Texan, legendary statesman

Former Speaker of the House Jim Wright was congressman for all the people.

Letters

Chancellor’s Letter: We’ve Got the Wright Stuff

Congressman Jim Wright’s papers are now part of Mary Couts Burnett Library’s Special Collections.

Features

A Look Inside Special Collections

The library’s vault of historic writings and artifacts chronicles the history of TCU and Fort Worth.