Childhood Poverty Can Lead to Adult Obesity

An upbringing marred by poverty and food insecurity can stay with people as they age, even manifesting as adult obesity.

Getty Images © Lew Robertson

Childhood Poverty Can Lead to Adult Obesity

An upbringing marred by poverty and food insecurity can stay with people as they age, even manifesting as adult obesity.

Sarah Hill, associate professor of psychology, published two recent studies exploring the subconscious mind’s powerful influence over the urge to eat.

“When you grow up in an environment of unpredictability, it often includes unpredictability in access to food,” Hill said. “What we hypothesized was growing up poor would lead people to eat when they were not hungry.”

Uncertainty about the availability of meals often causes people to overeat when food is present. “It makes sense to eat when you’re not hungry because you can store calories,” she said. “That’s been the case throughout most of [humankind’s] evolutionary history.”

Dialing back that ancient impulse can be difficult. And the more desperate the childhood situation, the harder the recalibration. “It’s kind of like taking a long road trip,” Hill said. “If you have half a tank of gas, you still might get gas where you can because you don’t know what’s ahead.”

Hill and her research team found that, without conscious intent, people who grew up poor would overeat long after reaching the safe destination of financial security.

Poverty’s Long Shadow

A two-year grant from the Anthony Marchionne Foundation helped fund one of Hill’s investigations into the link between early financial security and adult eating habits. Hill and a team of graduate students conducted the study using TCU undergraduates as research subjects.

“All the differences we found were based on their childhood environment,” the professor said. “We did not find that their current economic condition had any effect.”

In the first part of the study, researchers asked 31 female students from various socioeconomic backgrounds about their hunger levels and then offered them snacks.

In the second part, 60 female students fasted for five hours before participating. Half of the subjects drank Sprite upon arrival; the other half drank water. After 10 minutes, researchers recorded the students’ blood-glucose levels and gave them food.

Finally, 82 research participants repeated the fasting-drinking sequence before having their energy levels assessed by the blood-glucose measurement. They could then eat as many snacks as they desired.

In each group, participants from higher-income childhood homes better regulated caloric intake. When students from more privileged backgrounds drank Sprite, they ate less. Students from lower-income backgrounds ate more regardless of the drink.

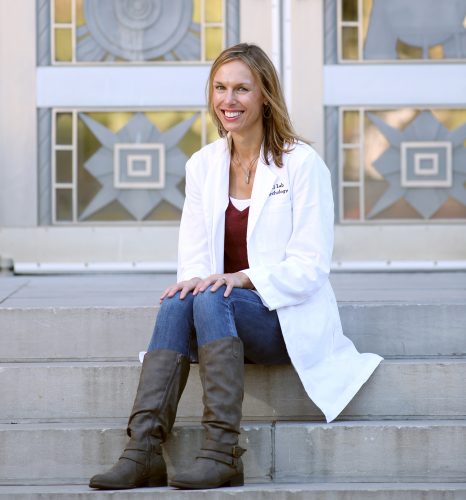

Sarah Hill, associate professor of psychology, TCU college of science and engineering. Hill conducted research on the link between childhood poverty and adult obesity. Photo by Carolyn Cruz

Survival Mechanism

Hill’s group was not the first research team to find a link between childhood poverty and adult obesity. But the professor’s work is innovative in proposing that the association might be tied to children’s developmental adjustments to resource-scarce environments.

Overeating, a former survival mechanism, can result in obesity as the child grows into a more stable adulthood with readily available and affordable food.

“We found support for our hypothesis” across the three parts of the study, Hill wrote in the research paper, published in the journal Psychological Science.

Among people who grew up in more affluent environments, food intake varied according to the immediate physiological energy need. These people consumed more calories when their energy need was high versus when it was low.

For people who grew up in low-income environments, however, food intake appeared to be guided primarily by opportunity, Hill said. “They consumed high numbers of calories whether their current energy need was high or low.

“There’s a role that body awareness plays into all of this,” she said. “For those who tend toward obesity, there is less awareness of bodily cues in general. They’re not really sensitive to when they’re full.”

The Lure of Cookies

The second study conducted by Hill’s team examined the belief that healthy foods are more expensive and less convenient to prepare and how environmental food cues affect that belief.

“We found evidence that one’s food-related motivations may impact their beliefs about the cost of healthy eating,” Hill said. The components of a healthy diet, in truth, are no more expensive than foods low in nutritional value.

Hill’s research methodology included interviewing groups of fasting students in either a neutral room or one imbued with the smell of baking cookies.

“Our brain does a lot of self-deception. In the presence of a tasty cue, we’ll tell ourselves stories about why we should eat these foods,” Hill said. “Food is about acceptance and community, but it comes at a social cost.”

Study participants who expressed the belief that healthy foods were more expensive often had a higher body-mass index and poorer eating habits.

Participants who rejected the idea of unaffordable healthy foods tended to be people who were dieting or otherwise concerned about body image or weight, as gauged by survey responses.

“Because restrained eaters are highly motivated to restrict their caloric intake, they regularly generate effortful cognitive and behavioral defenses in the presence of tempting foods to prevent themselves from indulging,” Hill wrote in the paper, published in the journal Appetite.

Nondieting participants tended to agree with the idea of unaffordable healthy food more when in a cookie-scented room than when in an unscented room.

The opposite pattern emerged for participants who were trying to restrict caloric intake. They reported more skepticism of the expense of healthful eating in the cookie-scented room compared with those in the unscented room.

“The results of our studies provide evidence that consumers’ beliefs about the cost of healthy eating may be influenced in important ways by their food-intake goals,” Hill said. “The results of these studies suggest that thinking objectively about food may be challenging for consumers, particularly in contexts with an abundance of palatable food cues.”

Hill’s research plans include additional studies of the hormones ghrelin and leptin, which also influence eating behaviors, and adults’ various motivations to regulate caloric intake.

Despite the research, a grim future of illness and obesity isn’t inevitable for people who come from harsh beginnings or hold false beliefs about healthy food, Hill said. “Anyone, with great willpower, can change their eating habits.”

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related reading:

Campus News: Alma Matters

Food for thought

Ranch Management class explores sustainable food production.

Alumni

Replenish Bottles are Jason Foster’s New Career Venture

Wall Street and Hollywood prepared Jason Foster for the sustainable spray container venture.Campus News: Alma Matters

More than Cooking

Students learn to plan, prepare and present gourmet food, with a focus on nutritional value and visual appeal.