Class Travels to U.S.-Mexico Border Wall

Justice Journey illuminates Chicano culture in Texas in conjunction with the Latino/a Civil Rights Struggles course.

Class Travels to U.S.-Mexico Border Wall

Justice Journey illuminates Chicano culture in Texas in conjunction with the Latino/a Civil Rights Struggles course.

Approaching the border wall — the one that already exists between the U.S. and Mexico — was an unforgettable experience for Alyssa Clark ’17.

“When you think about the border wall, it’s very symbolic to immigration,” said Clark, who earned a degree in political science in May. “Then you see it and for [immigrants], it’s concrete.”

Clark and 18 classmates visited the helicopter-patrolled border area near McAllen, Texas, as part of the TCU Justice Journey in March.

The wall wasn’t what Clark was expecting. Parts of it are made of wood or metal posts. In other areas, there are vast stretches of land with no wall at all.

“The concept we were struggling with [on the trip] was that borders are man-made,” Clark said, “and there is no reason for this wall to exist because the land across is the same as the land here.”

Bus Trip’s Origins

The Justice Journey bus trip during spring break took place in conjunction with the Latino/a Civil Rights Struggles course. Emily Farris, assistant professor of political science, and Max Krochmal, assistant professor of history, taught the course, which was modeled on examinations of the African-American civil rights movement.

For the spring semester, Farris and Krochmal focused on the Chicano movement of the 1960s, which sought to empower and achieve institutional equality for Mexican-Americans.

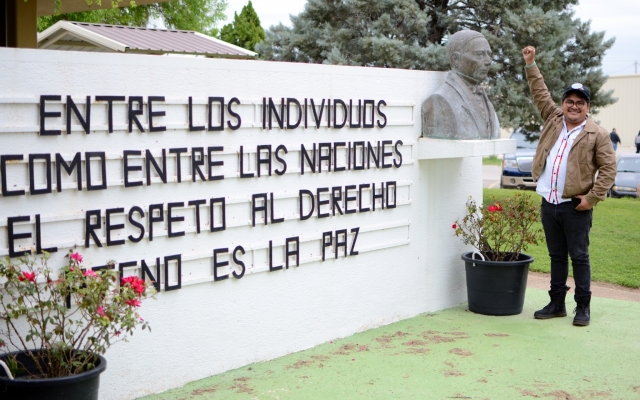

In discussing immigration law and delving into what it means to be a Chicano, the professors and students traveled to important locations in Chicano history in Texas, including Austin, San Antonio and the Rio Grande Valley.

The bus trip, Krochmal said, was “a chance for students to see normal people at the very bottom of our economy who have been able to come together and improve their situation and advocate for themselves.”

“Our mission as an institution is about preparing students to be active citizens and ethical leaders in a global community,” he said. “To do that, we have to expose students to a range of experiences and we have to help them think about differences and how certain communities have access to resources that others don’t.”

Students and Allies

Clark said she was excited about exploring her Latina heritage. “I wanted to learn about the history my [high] school didn’t teach me.”

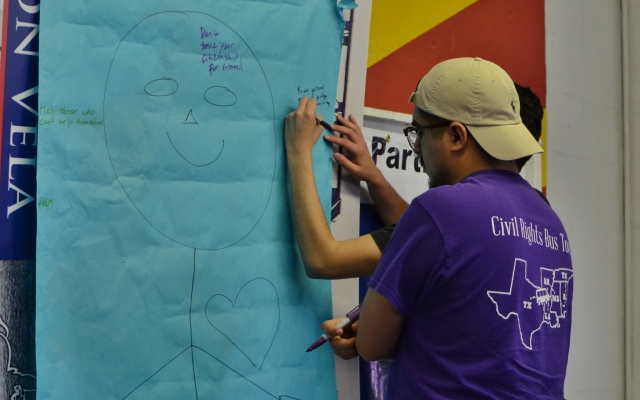

Samuel Ramirez ’17, took the civil rights bus tour in 2016. He said he wanted to take the Chicano course because it pertained to his ethnic background.

“Growing up in Texas, I didn’t really get that side of history,” Ramirez said. “I didn’t really get a lot of insight on how people like me were able to advance in the U.S.”

But not all of the students on the Justice Journey identify themselves as Chicano or Latino.

Mackenzie Holst ‘17, who went on the trip, said more white people should fight for racial equality alongside people of color.

“I’m always striving to be a better ally, and that means more than just writing ‘Black Lives Matter’ on Facebook statuses,” Holst said. “Going on this trip actually gave me historical and cultural context for what we’re fighting for.”

Ramirez said people of all ethnic backgrounds should learn about cultures different from their own and the Justice Journey is important for more than the 12.1 percent of TCU students who identify as Hispanic or Latino. “It’s good for other people to take [the course] and become allies. It creates that unity between cultures.”

A Week to Remember

During the weeklong trip, students were immersed in Chicano culture through discussion panels with activists such as Rosie Castro, one of the first Chicanas to seek elected office in Texas. The students’ itinerary included tours of historical sites such as Mission Concepción in San Antonio, where Franciscan friars converted Native Americans to Catholicism.

At the border wall, students listened to undocumented immigrants tell stories about living in the United States. Some, whose parents brought them to the U.S. at a young age, “don’t know what life is like in Mexico,” Clark said. “They only know America. They told us how they are every bit as American as you and me except for they don’t have that paper. I learned that they are people, not a number.”

The students also visited two public murals in McAllen painted by local artists to depict the Chicano community and culture. Holst said she was moved by the contrast between the artwork and the imposing border wall.

“There are walls that divide us and walls that bring us together. It just depends how we use them,” she said. “You look at the [border] wall and it’s hateful, and then you drive just down the road and you see signs of love and community.”

Political Climate

In the wake of crackdowns in the U.S., Farris said, immigration and Chicano history were timely topics for class discussion. “Thinking about the issue of immigration, immigration rights and how Latinos have approached the question of immigration over time has helped inform students in thinking about how to approach this moment in time.”

In studying Latino voting power, students in the course registered Latino youth in Fort Worth to vote. Holst said the students registered more than 250 people overall.

Clark’s group registered about 50 people during visits to two high schools and a community center. “I really want to see that I can make an impact on Latino youth,” she said. “I really want to be that change. I hope that I can see that I’m doing something for the community.”

Ramirez said the national debate over immigration helped bring Latino issues to the forefront for him.

“This whole political climate is giving us a chance to speak up,” he said. “We grew up being proud of our culture and knowing that we are important, and it’s time to put that into action. This is the time. There is no other time to do it.”

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related reading:

Campus News: Alma Matters, Research + Discovery

Max Krochmal on the Liberal Roots of Texas

History professor’s new book examines the power of multiracial Democratic coalitions in mid-20th century Texas.

Campus News: Alma Matters

Race, Ethnicity and Politics and Texas

With the 2016 release of his first book, Max Krochmal stepped into the national spotlight as an authority on social justice and activism in the Lone Star State.

Features

Peace for the Next Generation

Jaime Horn ’98 trains female negotiators.