The American Scholar in our time . . . Valerie Neal ’71

Emerson would delight in today’s technology, but he’d be prouder still of our pursuit of knowledge and creativity.

The American Scholar in our time . . . Valerie Neal ’71

Emerson would delight in today’s technology, but he’d be prouder still of our pursuit of knowledge and creativity.

Editor’s Note: The TCU Honors Program, which gained the moniker John V. Roach Honors College in 2009, marked its 50th academic year this spring. The college welcomed one of its own in April as Valerie Neal ’71, curator of the Space History Division at the Smithsonian’s National Air & Space Museum, gave the keynote address at Honors Convocation. Here is an edited excerpt.

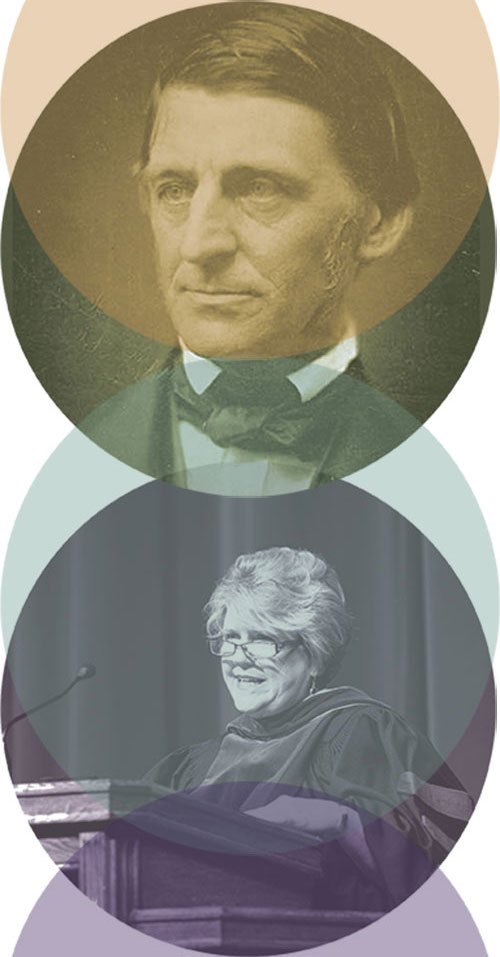

Among the influential people I met at TCU was Ralph Waldo Emerson, who 176 years ago gave a notable address to the Phi Beta Kappa Society at his alma mater, Harvard.

It was a declaration of intellectual independence and an assertion of a distinctively American style of scholarship. Emerson’s title was “The American Scholar,” and the lecture was so well received that Phi Beta Kappa adopted the same title for its scholarly journal.

While endorsing the “love of letters,” by which he meant literature and the liberal arts, Emerson departed from the importance of the classics and traditional learning and claimed radical new foundations for the educated American.

The first and primal influence must be nature, as he understood it — the unity of life, creation, soul, spirit, mind. Contemplation of nature in its myriad guises, in all the parts of its whole — through the sciences, the arts and literature — reveals the transcendent truth that everything is connected. “Know thyself” and “study nature” were to Emerson the same maxim, the same path to insight and understanding.

Next must be the mind of the past, “in whatever form … the mind is inscribed”… books especially, yet he said, “Books are for the scholar’s idle times.” He sought to distinguish thinkers from “Man thinking,” or in today’s non-gendered form, “Scholar thinking.” Mere thinkers learn the knowledge of the past, but scholars create new knowledge for the present and future. Emerson argued for “creative reading” as well as “creative writing.” He thought the proper use of books is to inspire, and “each age must write its own.”

The other great influence is action. The American Scholar must live and work, not be a recluse in an ivory tower. Book learning is not enough. Action “is the raw material out of which the intellect molds her splendid products. Only so much do I know as I have lived,” Emerson claimed. “Life is our dictionary.”

Emerson next addressed duty. It is the duty of the thinking American Scholar “to cheer, to raise and to guide” others. The scholar must be free, brave and confident to stand up to controversy and criticism, with a duty to elevate human discourse and understanding.

And so we have a 19th century model: The Scholar is alert, aware, engaged. The Scholar is original. The thinking Scholar turns action into ideas and ideas into inspiration.

Skipping ahead almost two centuries, does the Emersonian model have vitality today, or are there now different hallmarks of the American Scholar?

Certainly the methods of scholarship are dramatically different, thanks to advances in computing and communications technologies and also in learning theory. We have access to information, and can manipulate it in breadth, depth and speed that keep increasing.

We can do research in moments by using one finger on a device held in the palm of our hands, or we can do collaborative research across time and space with ease. We are connected — instantaneously — not only to information but to vast global networks of people and images and experiences. Knowledge and scholarship are truly global in scope.

We think and absorb and synthesize and create so rapidly, in so many modes, and so communally that today’s scholar can hardly be a solitary individual.

Today’s thinker is armed with technology and connections that vastly expand the range of inquiry, learning and the community of scholars. I think Emerson would have delighted in cell phones, iPads, virtual reality, lasers, Google, Windows and Adobe software — everything that today improves our knowledge and creativity.

But what about the fundamentals of becoming and being a scholar? Today I look to what you are doing here — your curriculum, activities and stated values. Over the past few years, and especially this week, I have been observing the nature of scholars and scholarship at here at TCU:

- Your “Big Questions” discussion groups strike me as a fine example of the kind of provocative, original thinking that Emerson had in mind. Your focus on “critical thinking and creative inquiry” is certainly germane, as is your emphasis on collaboration and community involvement.

- The caliber of honors research projects I witnessed this week speaks volumes about the originality of students and their mentoring faculty.

- The Core Curriculum is both practical in its insistence on essential competencies and challenging in opportunities to expand your exploration of intellectual and cultural heritages.

- And one can almost hear Emerson in TCU’s mission statement: To educate individuals to think and act as ethical leaders and responsible citizens in the global community.

I think that Emerson himself would admire what is happening here. Your educational experience arises from the influence of nature, the mind, action and duty — although TCU expresses them in different terms. It is obvious that TCU is focused on producing scholars — not only American but around the world — who are engaged, original, active, ethical and prepared to make a difference globally.

Before coming here this week, I dredged up my TCU transcript as a reality check on my memory. Sure enough, there were the unforgettable literature and history courses, music and art appreciation classes, a most challenging philosophy course, three years of foreign language study, an unhappy experience in golf, regrettably too little science and math. There were the “Big Questions” Honors Colloquia of my day: The Nature of Man, The Nature of Values, The Nature of Society and The Nature of the Universe. Many of these courses, and those who taught them, remain active in my consciousness.

Although I set out to become a professor, I am often asked how I came to have such a different career or how I managed to land in the Smithsonian. It wasn’t my plan, and if it had been I might not have been able to make it happen. Without my knowing it at the time, the path began in the Honors Program at TCU, where I really learned how to learn. It was Dr. Fred Erisman who introduced me to Emerson, the American scholar who became my muse.

Although the focus of my graduate education was 19th century American studies, I developed an interest in the history of science in that era. That interest in science and the ability to do research, learn, think and write opened the door to NASA and to working with scientists and engineers. Writing about science on Space Shuttle missions for NASA opened the door to the space history division at the Smithsonian. And being a scholar in the Smithsonian — one of the world’s great research institutions, dedicated to the increase and diffusion of knowledge — opened the door to return to TCU to join you today.

There is serendipity and symmetry in life, and things come full circle. Everything is indeed connected!

To the students here today, I urge you to cherish the scholars who have influenced you and keep them in your life. And to the faculty, try to keep an eye on these students when they leave. They may astonish you in the highly original ways they live as scholars.

On the Web:

See more on the Honors Program through the decades

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related Reading:

Alumni, Features

CHEW to the Rescue

A desire to help dogs led Leigh Owen Sendra to launch a nonprofit veterinary clinic.

Alumni, Features

Finding a Fit

A Neeley alum matches workers on the autism spectrum to high-tech careers.