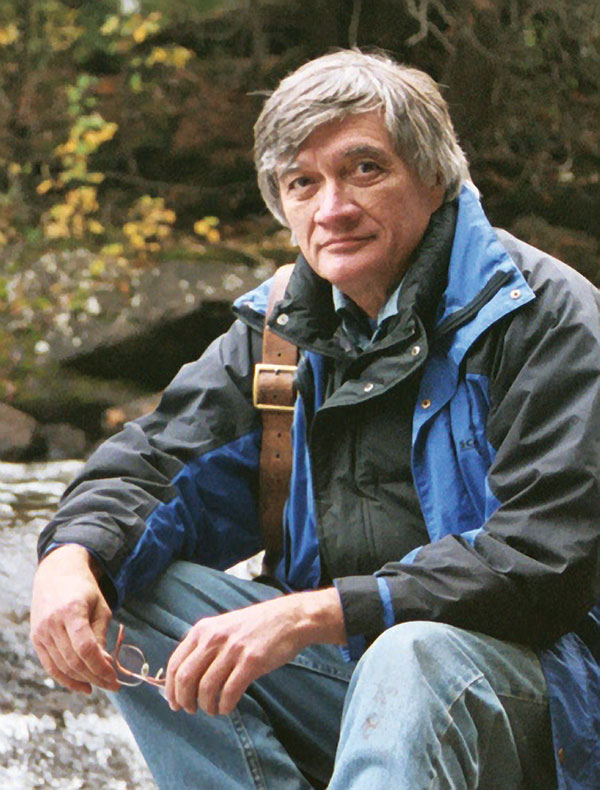

Power mandate . . . nuclear waste scientist Rodney Ewing ’68

Appointed by the president to lead the Nuclear Waste Technical Review Board, Rod Ewing ’68 is advising Congress on the safest, most logical way to safely dispose of spent nuclear fuel.

For 40 years, Rod Ewing '68 has studied the long-term behavior of man-made materials from those found in nature. Last year, he was tapped to lead the Nuclear Waste Technical Review Board.

Power mandate . . . nuclear waste scientist Rodney Ewing ’68

Appointed by the president to lead the Nuclear Waste Technical Review Board, Rod Ewing ’68 is advising Congress on the safest, most logical way to safely dispose of spent nuclear fuel.

At first meeting, Rodney Ewing ’68 puts you in mind of a mountain. Not that he’s large. But he’s got a rock-solid presence.

It’s just the kind of presence our country needs right now. Which is why President Barack Obama appointed him as chair of the Nuclear Waste Technical Review Board last year, directing him to advise Congress on the safest, most logical way to safely dispose of spent nuclear fuel. It’s one of the most pressing problems of our time.

In a way, Ewing has been researching that question ever since geology Professor Art Ehlmann’s mineralogy course lured him from chemistry to geology, where he discovered metamicts.

Metamict minerals look rugged on the outside. Inside, their atoms are all askew. While they start out in rigid crystalline perfection, over time, radioactive elements within the minerals change their ordered atomic structure. Trying to understand that transition from symmetry to chaos, how radiation damage affects metamicts, and how to predict the long-term behavior of man-made materials from those found in nature has occupied Ewing for more than 40 years.

Maybe it’s the ability of metamicts to withstand damage but stay intact that drew him — like to like. “I am very stubborn. Unbending, so my colleagues tell me,” says Ewing.

Encouraged to apply to graduate school by Ehlmann, Ewing was accepted at Stanford, where he received a National Science Foundation fellowship. Soon after, his number came up for Vietnam. He was against the war and contemplated Canada.

“But in the end, avoiding it didn’t seem right,” he says.

Ewing scored high in language skills, and was sent to learn Vietnamese, then spent seven months in country. Of course it changed him, says Ewing. He doesn’t elaborate.

After his return, he went back to graduate school, studying like with a professor at Stanford. But the professor died soon after.

“I thought I could just quietly study these minerals in obscurity, and nobody would bother me for the rest of my life,” he recalls.

It didn’t work out that way. After completing his PhD, Ewing was hired by the University of New Mexico, where he met speakers from Los like and from the national labs. They were all talking about waste forms, the highly durable barrier meant to prevent the release of radionuclides in the storage of high-level nuclear waste.

Ewing learned that the material the government had decided to use as a waste form was glass, yet from a scientific point of view, he says, “Glass is very unstable. Glasses don’t last. It struck me as an interesting and not very attractive solution.”

Metamicts, naturally-irradiated yet strong minerals, were still on his mind. He began to talk about waste forms a bit more formally. And write about them. He sent an editorial to Nature, and to his surprise it was published.

“But no one was too interested in the idea that we could infer the long-term behavior of materials used in radioactive waste disposal from natural glasses,” he says.

Still, an investigator at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory contacted him to do some research, “putting radioactive materials into minerals and studying the effects on them. I realized by studying metamict minerals that they were a good analog for nuclear damage in waste forms.”

Still, an investigator at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory contacted him to do some research, “putting radioactive materials into minerals and studying the effects on them. I realized by studying metamict minerals that they were a good analog for nuclear damage in waste forms.”

From those early days, Ewing’s fascination with metamicts grew into an idea now widely known as “natural analogues” — using geologic materials of great age to evaluate radiation effects and erosion on other materials that could be used as waste forms for spent fuel.

Over the years, Ewing’s research has led him to publish more than 650 papers for materials science, nuclear, geochemistry, physics and mineralogy journals. Now a professor in the Departments of Earth & Environmental Sciences, Nuclear Engineering & Radiological Sciences, and Materials Science & Engineering at the University of Michigan, he is also co-editor of, and a contributing author to, two books about radioactive waste disposal.

But a long and prestigious career is never accomplished single-handedly.

“TCU was very good for me,” Ewing said recently. He credits English professor Betsy Colquitt for teaching him how to write: “She was a model of clear thinking and writing.” And Art Ehlmann inspired him, “to work hard and move ahead.”

On April 11, at a hearing on Nuclear Programs and Strategies, Ewing advised the energy and water development committee that a deep geologic repository will be needed for storing nuclear waste, “regardless of the fuel cycle option selected.”

Also, in terms of gaining public consent for selecting the site for the repository, he noted that “ongoing, independent technical oversight of the activities undertaken by the implementer of a consent-based repository-siting program is crucial.”

Two weeks later, a bipartisan group of four senators released a draft bill proposing a new federal agency to oversee the disposal of spent nuclear fuel. The plan authorized a newly formed agency to set up a temporary waste storage facility while potential permanent sites are identified and vetted through a process based on public consent.

“We can and should move to consolidation of spent fuel at an interim storage until a permanent site can be built,” says Ewing. “This can be done, and safely.”

But as we saw with Yucca Mountain in Nevada, which was scrapped as a potential nuclear waste repository, the public has to agree on where to locate the site, or it can fail.

Ewing has served on 11 National Research Council committees for the National Academy of Sciences that have reviewed issues related to nuclear waste and nuclear weapons. In 2008, he was a technical cooperation expert for the IAEA at the Comissão Nacional de Energia Nuclear in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

He is convinced that the public must be involved and informed about nuclear fuel waste. “Since Fukushima, discussions within the National Research Council reveal that a fair amount of activity goes into trying to inform the public, but discussions are handled in such an arcane way that the public can’t see or understand the information as it’s presented.

“The challenge to scientists and engineers is to be in credible dialog with local communities. But we are not skilled at that. We have to work with people to address their fears of radiation. We must be in touch with the public.”

At the moment, the Nuclear Waste Technical Review Board he chairs is “one venue that can have contact with people. You have to convince the community involved that you know what you’re doing.”

If anyone can, it’s Rod Ewing.

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related Reading:

Alumni, Features

CHEW to the Rescue

A desire to help dogs led Leigh Owen Sendra to launch a nonprofit veterinary clinic.

Alumni, Features

Finding a Fit

A Neeley alum matches workers on the autism spectrum to high-tech careers.