COURTNEYK | E+ | Getty Images

Power to Change

The Ralph Lowe Energy Institute seeks to prepare students for the future of energy.

Tejal “TK” Kshatriya knows that many rural residents in her native India still use dry cow dung for cooking fuel because they lack adequate power supplies. She also knows that energy accessibility and affordability issues exist in the United States.

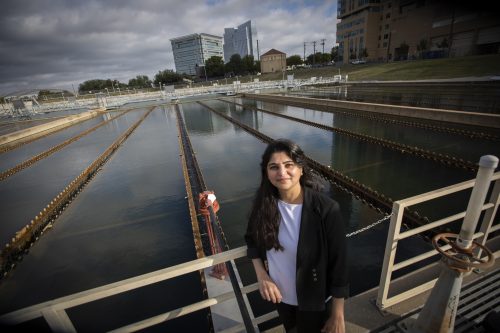

Energy MBA student Tejal Kshatriya is studying socioeconomics to help the Fort Worth Water Department develop its own energy sources from waste products. Photo by Rodger Mallison

As a TCU Energy MBA student, Kshatriya is learning how to reduce both types of energy poverty, a term meaning when people lack access to reliable, affordable energy to meet basic household needs.

“There’s so much to learn,” she said, “that I’m just scratching the surface.”

The university created the original TCU Energy Institute 15 years ago after the discovery of oil and gas in Texas shale. In 2021 it was renamed the Ralph Lowe Energy Institute at the TCU Neeley School of Business. Its goal is to generate a steady stream of industry leaders and research.

Today, the institute is pivoting toward a broader mission and curriculum to better prepare students — and the organizations they belong to — as the energy field expands to include renewable and sustainable power sources such as wind and solar.

“We’re in the midst of a critical transition in one of the largest commodity markets in the world — and talking about how this affects access to energy,” said Ann Bluntzer, acting director of the institute who developed the Energy MBA program. “We will need more energy, all types: fossil fuels, renewables, nuclear and hopefully new technologies that haven’t been invented yet in order to move to a clean energy future.”

Globally, nearly 800 million people don’t have access to electricity, and more than 2.6 billion people, largely in sub-Saharan Africa, rely on fuel like biomass, kerosene or coal for cooking, the International Energy Agency reports.

Energy poverty and economic poverty often go hand in hand. Limited access to energy can mean children don’t have adequate lighting to do homework at night, which may hinder their education and subsequent employment opportunities. It may contribute to unhealthy living conditions and health issues like malnourishment caused by not having enough cooking fuel.

The answer may lie in a hybrid model of legacy and renewable energy sources that can “start to move the needle and make a dent,” Bluntzer said. “For some highly populated countries like India, look at how many people are still burning wood for basic needs like cooking food or providing heat. In India, going 100 percent renewable would take a long time.”

A mix of options might improve energy access for nearly 1 billion people, providing a route to being able to power a laptop or refrigerate food.

Positive End

Bluntzer, an associate professor of professional practice in the management and leadership department, said she wants to “lead conversations as to how we, as a business school, can effect positive change for people directly related to energy.”

Ann Bluntzer, acting director of the Ralph Lowe Energy Institute, developed the Energy MBA program. At the institute, she said, “we want to depoliticize the conversation around energy.” Photo by Rodger Mallison

In addition to its Energy MBA, the institute offers a nine-month graduate energy certificate program and an undergraduate minor. As of fall 2021, the institute was home to 120 energy graduate, certificate and undergraduate students.

Bluntzer is leading an expansion of the curriculum to address energy poverty, climate and other broad topics. The school recently added a second certificate focused on sustainability and environmental and social governance (ESG).

Last year, the institute moved from the College of Science & Engineering to the business school. “The Neeley School of Business, along with our Energy Advisory Board,” Bluntzer said, “is able to provide the necessary leadership to help solve the most critical issues facing the energy industry due to our legacy relationships with some of the most innovative energy companies in the world.”

Bluntzer said she relishes the challenge of forging new territory in the energy industry. In discussions about energy transition, “we get hung up in politics. … We [through the institute] want to depoliticize the conversation around energy.”

She and Mike Slattery, chair of environmental sciences in the College of Science & Engineering, are developing an Energy MBA curriculum that includes courses on energy poverty and on how energy companies are transitioning from fossil fuels to sustainable and renewable energy.

The duo also hopes to develop undergraduate classes on renewables and climate.

“When you look at energy consumption, delivery and production, you really can’t ignore energy poverty because access to energy is not equally distributed around the globe,” Slattery said. “Students are surprised when first exposed to these statistics … but they’re also ready to make a difference.”

Students aren’t just learning about energy poverty on a global scale but also closer to home.

While most Americans have access to electricity, one-third of U.S. households, about 37 million, experience energy poverty, Nature Energy reported in 2020. Research also shows that low-income households — those with annual income of $24,998 or less — spend up to three times more of their income on energy as households that make up to $90,000 annually, and many have had to forgo food and medicine to pay utility bills.

Mike Slattery, chair and professor of environmental sciences, is working with Ann Bluntzer on the Energy MBA curriculum. “When you look at energy consumption, delivery and production,” he said, “you really can’t ignore energy poverty because access to energy is not equally distributed around the globe.” Photo by Rodger Mallison

“Power is expensive when demand is high in many dense, urban areas, such as Houston and Dallas, and many people can’t pay to heat and cool their homes,” Bluntzer said. “For us in America, it sounds like a first-world problem when compared to places that have no power, but it’s relative.”

Testing Theories

TCU students can apply theory to real global situations in the Energy Innovation Case Competition, where teams from universities across the nation have a few hours to propose innovative solutions to an oil and gas industry problem.

The second competition, which took place in February 2021, focused on energy poverty and transition. Student teams analyzed the potential positive financial effect on Bangladesh, India or Nigeria if several public energy companies shifted toward sustainable sources.

The goal is to “give students an opportunity to tackle a problem that energy companies are currently facing,” said Le’Ann Callihan ’90, vice president of Fort Worth-based AAPL/NAPE, an oil and gas industry professional alliance that co-sponsors the competition with TCU. “Many companies are increasing their efforts in the environmental and social governance realm, and finding solutions to energy poverty is a part of that responsibility.”

TotalEnergies, one of the world’s largest oil and gas companies, with operations in Fort Worth, is among a growing number of companies and countries setting net-zero emission goals by midcentury to reduce or offset the greenhouse gases released into the air during the production or use of oil and gas. Greenhouse gas emissions trap heat and cause the Earth’s temperature to rise.

For TotalEnergies, meeting that goal means investing heavily in renewable sources including hydrogen technology, biofuels, solar and onshore-offshore wind. Such clean energy may provide more affordable, reliable options for people around the globe who have no access to any energy.

“Getting out there across the world is what we all want to do,” said Dave Leopold, ’96 MBA, CEO and president of Fort Worth-based TotalEnergies E&P-Barnett, an affiliate of French-owned TotalEnergies. “If you’re only burning wood to cook your meals or keep warm, that’s pretty tough.”

The university’s energy initiatives provide a path “to better ourselves and better our companies, and now I think it’s extended to better mankind,” said Leopold, who also is co-chair of TCU’s Energy MBA Advisory Board.

“Getting a different perspective allowed me to take on more project management-type roles.”

Georgeanne Dollar

“We want to provide the framework for students to figure out how to address energy poverty.”

One problem in doing just that is the data is fragmented, Bluntzer said. So she proposed the Energy Global Alliance, a think tank within the institute designed to collect and share global energy poverty data and research.

“It’s hard to get a lot accomplished when you’re operating in silos,” said Georgeanne Dollar ’02 (MBA ’20), who led the nascent alliance as part of her capstone project before graduating. The alliance aims to break down those silos.

Many TCU Energy MBA students are working professionals like Dollar and Kshatriya, both in their early 40s. They both said that their growing knowledge of the energy industry has led to more responsibility at work.

“Getting a different perspective allowed me to take on more project management-type roles,” said Dollar, who is lead land tech at EOG Resources Inc. in Fort Worth. “I probably wouldn’t have done it without getting the exposure and confidence in the MBA program.”

Bluntzer said the results make her smile. “Part of TCU’s mission is to effect change in a global sense and to do that through education,” she said. “We need to make sure our students leave here with the tools to help nonprofits and private companies prepare for the future of energy.”

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related reading:

Campus News: Alma Matters

How can we conserve water for the future?

Three TCU water experts weigh in with practical advice.

Features

Discovering Global Citizenship, or How to Help a Vanishing Species

TCU’s award-winning international education program is making an impact on South Africa’s endangered rhinos.

Features

Energy Institute’s Advice for Mineral Owners

Pioneering program doles out the know-how for securing successful oil and gas leases.