Photo by Joyce Marshall

Students Deal With Homelessness, Even at TCU

An unstable housing situation can present even more challenges for students trying to succeed in high school and college.

Jacob Trevino ’19 spent four years at Seguin High School in Arlington, Texas. To most, his days looked similar to those of any other student in the school of 1,500. He would wake up, catch a ride, chat with friends, attend theater rehearsals. Only a few close friends were aware of Trevino’s reality: He was homeless.

From ages 14 to 17, Trevino was an unaccompanied youth — a minor living without a parental guardian. Near the end of his freshman year of high school, Trevino’s mother left, and he described having a “rocky relationship” with the rest of his family. He ended up couch surfing his way through high school. He stayed with one friend for a year and continued to hop around to other friends’ homes.

Jacob Trevino now works as a counselor with the College Advising Corps at his alma mater Juan Seguin High School in Arlington, Texas. Photo by Joyce Marshall

Trevino said reaching out for support was a challenge. “A lot of people think that it’s a shameful thing, and that’s where I was at. … It wasn’t easy.”

Trevino may have felt alone, but he wasn’t, especially among his peers seeking higher education.

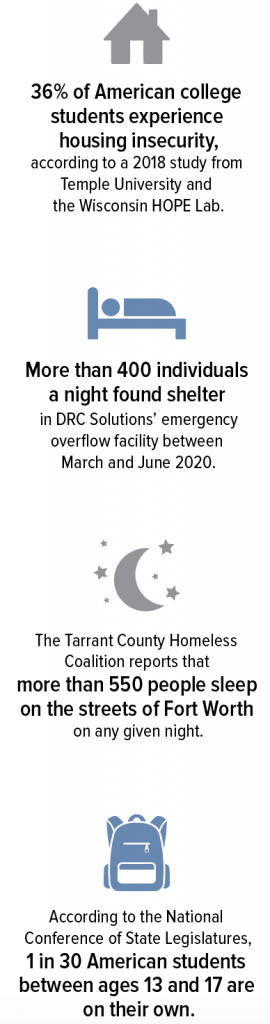

A 2018 study from Temple University and the Wisconsin HOPE Lab revealed that 36 percent of American college students experience housing insecurity.

And those numbers reflect a pre-pandemic world.

A Growing Problem

The Tarrant County Homeless Coalition reports that more than 550 people in Fort Worth sleep on the streets on any given night. Many of them congregate near downtown along East Lancaster Avenue, where some seek warmth in nearby shelters. Hundreds of people are usually on the area’s sidewalks, some with all of their belongings in trash bags.

“The local government officials decided that was how they wanted to attack the issue of homelessness, to kind of put it all in one area,” said Tony Wilson ’16 (MSW ’18), who has devoted his career to aiding people who are experiencing housing insecurity.

Wilson is the lead navigator at DRC Solutions in Fort Worth. The organization provides temporary shelter in a facility on Lancaster Avenue and helps people get into safe, stable housing. He coordinates stays at the shelter and walks residents through the job application process.

The majority of the 2,000 people looking for help from DRC Solutions each year are 40- to 64-year-old men, Wilson said. But young people who have just been released from jail or have escaped an abusive relationship also knock on the door for assistance.

When the coronavirus pandemic spiked for the first time last spring, the homeless population in the city skyrocketed. Numerous businesses temporarily shut down or laid off employees, leaving thousands of residents struggling to find an income or pay rent, Wilson said. “It’s been a whirlwind.”

When the coronavirus pandemic spiked for the first time last spring, the homeless population in the city skyrocketed. Numerous businesses temporarily shut down or laid off employees, leaving thousands of residents struggling to find an income or pay rent, Wilson said. “It’s been a whirlwind.”

To address the influx of people on the streets, city officials reached out to DRC Solutions for help setting up an emergency overflow shelter at the Fort Worth Convention Center downtown.

Recreational vehicles supplied with food and toiletries were placed in the parking lot to quarantine homeless people who were Covid-positive.

Between March and June 2020, more than 400 individuals a night found shelter in DRC Solutions’ emergency overflow facility. Wilson said he is proud to be a driving force in providing aid to those in need. He hopes more resources will become available as the pandemic continues and the aftermath becomes clearer. “It basically comes down to that human level and being able to say, ‘What do you need? How can I help?’ ”

A Place to Study but not Sleep

James Petrovich, who was a professor of social work in TCU’s Harris College of Nursing & Health Sciences for 10 years, raised the alarm that people who need shelter can also be attending TCU.

Petrovich said people are often surprised when he mentions that he has met students without a consistent place to sleep. Through devoting his academic career to understanding homelessness, he has learned that circumstances leading to housing insecurity for college students tend to stem from problems in childhood and early adolescence. Young adult homelessness can be a result of an inadequate child welfare or foster care system, family backlash for those who identify as LGBTQ or an escape from abusive relationships.

Limited family support can translate into a lack of housing for college students.

The professor said a common misconception is the idea that homelessness can be defined only as someone living on the streets or in a shelter. In reality, unstable conditions like couch surfing qualify as well.

The typical challenges and stresses that come with college life — writing papers, studying for tests, choosing a career — are magnified for students who must fulfill academic duties while coping with an unstable living situation. Petrovich said that students living out of their cars will typically use the university’s recreation center to shower or spend long evenings in the library during the cold months.

Tony Wilson and James Petrovich noted the rise in Fort Worth’s homeless population due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Photo by Joyce Marshall

“With housing instability, students are struggling to find a safe, stable, secure place where they can do their work,” Petrovich said. “This is kind of a tragedy in the midst of trying to take on this huge undertaking, which is college, and learn and study and take exams. And then this is a really important developmental stage of their life. Socially, so many things are happening to a person at that age.

“Students should not have to answer the questions, ‘Where am I going to sleep tonight? When will be my next meal?’ ” he said. “Instead they should focus on their future and ask, ‘What do I want to do? What passion do I want to explore?’ ”

Paying it Forward

Thanks to a performing arts scholarship and other grants, Trevino found solid ground — and stable housing — as a TCU student. His first year on campus, he spoke with a counselor about his struggles with housing insecurity throughout high school. As the school year continued, he said, he felt increasingly comfortable in his new life. “It was nice to see myself progressing.”

As a theatre major, he performed in the Trinity Shakespeare Festival and directed TCU’s production of the play Black Comedy.

Jacob Trevino said he wants to help young people prepare for a successful future. Photo by Joyce Marshall

After graduating, Trevino joined TCU’s chapter of the College Advising Corps, whose mentors had helped him find an accessible route to college. He now works at his alma mater, Seguin High School, where he assists students with the college application process. Many of these students, Trevino said, are facing housing insecurities similar to what he experienced. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, 1 in 30 American students from ages 13 to 17 are unaccompanied minors.

When meeting with these students, he said, he always “lets them know that their spirit of resilience is really important. I let them know there’s a support network for them.”

Trevino is now pursuing a master’s degree in Higher Education Leadership at TCU. He wants to continue helping young students prepare for a successful future, no matter what they endured in the past. “It’s something that I’m incredibly passionate about.”

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related Reading:

Features

Making Their Case

From confidence to courtroom skills, TCU Mock Trial is shaping futures one case at a time.

Features

As TCU Provost, Floyd Wormley Jr. Leads with Heart, Humor and Hard-Won Wisdom

The academic leader brings clarity, conviction and a scientist’s curiosity shaped by years spent balancing lab work, mentoring and a growing call to serve in higher education.