Photo by Joyce Marshall

Seeking Strategies to Help Children With Dyslexia

Tracy Centanni hopes her research leads struggling readers to success.

Watching other kids leave the kindergarten classroom for recess while she worked to decode a single word is a distinct memory for Kate Cordle, a senior studio art major.

“I would normally be stopped by my teacher and escorted to a side room to work with her and two other students to try and at least get through the sentence,” she said. “They’d have to whisper what the words were to me so I could speed the process up and go outside.”

Cordle was diagnosed with dyslexia at age 5, but most children with the learning disability are not identified until second or third grade, when their reading skills are significantly lower than their peers’. Dyslexia is often called a diagnosis of failure. It’s the most common neurodevelopmental disorder, but children must fail at reading before they receive corrective instruction.

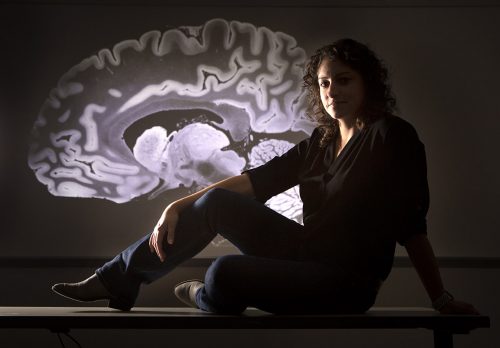

Tracy Centanni uses neural imaging to study dyslexia. She said her goal is to develop a school-based early identification and intervention program to treat dyslexia before young students learn to read. Photo by Joyce Marshall

Tracy Centanni, assistant professor of psychology, wanted to see if educators could learn to intervene before a student needed remediation. In her postdoctoral research, she started studying prekindergartners — some were at risk for dyslexia; others weren’t — and tracked their progress through second grade. At-risk children had a genetic predisposition for dyslexia or had trouble with early reading skills, such as recognizing the sounds letters make.

Using fMRI scanning, Centanni mapped activity in the fusiform gyrus area of the children’s brains as they were presented visual cues such as letters and faces. Her study found that the majority of children who demonstrated reduced brain activation in the fusiform gyrus when differentiating letters and faces had been diagnosed with dyslexia by the second grade.

Centanni said she hopes children with dyslexia can be diagnosed earlier to give them more time for intervention to close the reading gap with their peers. She also hopes schools begin to offer more methods of intervention to help students succeed.

Dyslexia affects up to 15 percent of the population. Psychologists originally thought dyslexia affected everyone the same way, Centanni said. But researchers are discovering that the disorder manifests in a variety of ways. Sufferers have trouble with a host of language and auditory processes such as differentiating sounds, matching letters to sounds, and naming letters, symbols and words automatically.

Psychologists spent decades trying to identify a single cause of dyslexia, but now the narrative is changing, Centanni said. “We’re looking at kids and adults with dyslexia as individuals that have different profiles. … They’re finding that dyslexia isn’t caused by just one problem in the brain.”

In her lab at TCU, assistant professor of psychology Tracy Centanni attaches an EEG net to the head of Kelly Brice ’19 MS. Photo by Joyce Marshall

This misunderstanding resulted in myriad unsuccessful intervention programs for young readers, she said. “You may have 10 kids in that grade with dyslexia. They’re all getting the exact same intervention because that’s the intervention that the school has, but they might not all benefit from that one.”

She said insufficient school budgets, understaffing and limited knowledge about the various causes of dyslexia often keep educators from implementing individualized intervention programs.

“You get these kids that are chronic nonresponders, and it’s not because they couldn’t benefit from intervention. It’s just because the intervention that’s available to them is not the right one for them,” she said. “And because the field is only now catching up, a lot of this information has not yet made it to the clinic or to the schools.”

One of Centanni’s long-term goals is to introduce individualized intervention programs into schools. She is planning the first phase of a large, randomized trial to test the effectiveness of different intervention models — based on sound awareness, fluency and meaning — on children with dyslexia.

“Hopefully that would provide some additional information for clinicians in schools to say, ‘If you have kids with dyslexia, you can’t just offer one thing. You have to be willing to adapt, and here’s some advice on how to do that. Here are the types of kids that work best with this intervention,’ ” Centanni said.

Some schools, including TCU’s Starpoint School, already offer a specialized environment for children with learning disabilities.

“The kids with the reading disorders like dyslexia [are] very, very smart. They just learn a different way,” said Lisa May ’04 MS, who teaches first-level students at Starpoint.

May said her son’s experience at Starpoint inspired her to get a master’s degree in special education so she could work alongside the teachers who helped him learn how to overcome the challenges of dyslexia. “He went through the entire program here at Starpoint School.” In December 2018, he graduated from TCU with a Bachelor of Science in ranch management.

Starpoint’s special reading curriculum teaches students to use their senses to better identify sounds, including tapping their arms to count syllables or shaping their mouths to distinguish the letter “P” from “B.”

Students “have trouble hearing the sounds, but if you can’t hear them, we’re going to teach you anyway. We’re going to teach you how to feel them,” May said.

Tracy Centanni uses information from an EEG to demonstrate the brain-mapping process she uses in her research on dyslexia. Photo by Joyce Marshall

Cordle benefited from a similar program when she started elementary school. It equipped her with tools that are helping her succeed at TCU. She said she still uses tricks she learned when she was younger, such as writing words while saying them out loud and writing in cursive.

“Honestly, reading as a whole has never been something I enjoy doing,” Cordle said. “Letters look like they’re floating on a page, so it takes a lot to get them in place. But this process is now expedited for me and happens pretty quickly.”

May acknowledged that many students do not have access to this kind of instruction and said she hopes Centanni’s research improves education for dyslexic students at every school.

“I hope that people learn to see that these kids have so much to offer this world. They have so many gifts and talents, and they can learn anything if we present it in the right way,” May said. “The sky’s the limit for these kids, but we have to give them the tools and the strategies to be successful.”

Your comments are welcome

5 Comments

This is incredible. My daughter was diagnosed with an auditory processing disorder, a form of dyslexia, at the age of 16 and we have been struggling to find her support in her schools. She is a senior in high school and we are looking for colleges where she will be supported with her disability. Does TCU offer these treatments to their students?

I have noticed for the last 2 years my daughter probably has dyslexia. She is 5 right now – she is extremely smart and has excelled in accelerated learning environments but reading and certain letters writing continue to be backwards or a struggle. II would love to use some of your strategies to intervene because the school system here won’t doing tests until 2nd grade.

I’m glad to see that researcher are starting to see that dyslexia is not the same for everyone and how it affects them. I know having it has been tuff in my life with reading and spelling. I hope with the research they are doing will help change the lives of students with dyslexia and teach them never to give up bc they can make it. Great article thank you all for writing it. GO FROGS

I am an adult with dyslexia, if I could be of any help in this research I would very happy to participate.

P D Hutchinson

gymdee3@aol.com

I suspected my daughter had a learning disability by the time she was 3. I didn’t act on it until she was 5 or 6 and i noticed a disconnection from sound and the letters the sound represents. I had her tested snd she was diagnosed with dyslexia and it was suspected she was spectrum. We started word walls and whole word vocab as well as sensory training We got her a spelling auditory reinforcement calculator (she could put in the word and it would pronounce and spell the word for her. Requiring her to re enter the word. It was somewhat helpful. By 3 rd grade she found a book series she loved and we challenged her to read it solo with the help of her calculator. It worked. She is 24. Is a voracious reader and is a current phd candidate in biomedical engineering. Amazing since the first therapist told us she would never be a fluent reader. Never give up. Kids are resilient. Find the method that works. Dyslexic kids just think differently.

Related reading:

Features

Starpoint School’s Special Education

At age 50, the on-campus lab school is still giving students a chance to shine.

Features

KinderFrogs Overcome Developmental Delays

Preschoolers with Down syndrome prep for traditional classrooms.

Alumni, Features

Allie Beth Allman is a North Texas Real Estate Mogul

The Dallas real estate agent sells high-end homes and gives back to the community.