Dr. Alison Lunsford Leads Nonprofit for Diabetic Children

The endocrinologist heads the Diabetic Foundation of the High Plains and runs Camp New Day.

Dr. Alison Hartman Lunsford ’03

TCU Major: Biology

Medical Specialty: Pediatric Endocrinology

The Nonprofit: Diabetes Foundation of the High Plains

Taygen lost 10 pounds in four days when he was 8 years old.

His mom, Randi Armstrong, carried him into a hospital in Amarillo, Texas. With his weight at 42 pounds, she said, she could count her son’s ribs connecting to his sternum.

“I thought he was going to die,” Armstrong said. “I really did.”

A woman at the entrance of the hospital identified Taygen as diabetic. She led them to the strollers and walked with them to the pediatric intensive care unit. A normal blood sugar level for an 8-year-old is between 70 and 150 milligrams per deciliter. Taygen’s blood sugar that day was 946 mg/dL.

A few days after diagnosis, Armstrong asked hospital employees about the greeter and described her. Nobody had heard of her. “My husband and I are convinced that God had put an angel in there. God knew how sick he was so the angel could show us where to go,” Armstrong said. “We literally had an angel take us to the PICU.”

Taygen, now 10, said he doesn’t remember much surrounding his diagnosis and hospital stay, but the medical team gave the family a crash course in Type 1 diabetes. The team also invited the boy to Camp New Day, hosted by the Amarillo-based Diabetes Foundation of the High Plains.

At the camp, children living in West Texas and eastern New Mexico learn to manage their chronic illness better and have the opportunity to do typical summer camp activities: swimming, hiking, arts and crafts.

Dr. Alison Lunsford, a pediatric endocrinologist, heads the Diabetes Foundation of the High Plains in Amarillo, Texas. Photo by Ralph Duke

Dr. Alison Lunsford, a pediatric endocrinologist in Amarillo, heads the diabetes foundation and was one of its founders. She was a year into her medical position at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center when a group of her patients’ parents approached her about funds they had raised and their desire to keep the money local. They met in Lunsford’s living room and outlined the foundation.

“Had these parents not approached me, and the right people and the right time and the right money come together at the same time, I don’t think I would have ever just started it willy-nilly, especially being new to this community,” said Lunsford, who is also an assistant professor of pediatric endocrinology at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center at Amarillo.

Community members rallied to create the foundation, she said. Local lawyers help set up the nonprofit pro bono. The Will Rogers Range Riders, a club that spearheads charitable activities for the Texas Panhandle, was an important catalyst. Rhonda McDavid, the executive director of the Southeastern Diabetes Education Services, served as Lunsford’s mentor.

One key point for the foundation was to financially support an ongoing diabetes camp and to provide scholarships for the children, as well as insurance and personnel.

In her volunteer position as president of the foundation, Lunsford champions fundraising, leads public engagements and runs Camp New Day.

Campers at Camp New Day enjoy camaraderie with other children coping with diabetes, as well as counselors (including Christian Clay on piggyback, far right, back row) who assist with medical needs. Courtesy of Alison Lunsford/Diabetes Foundation of the High Plains

Armstrong opposed sending her son to the camp at first. “I just said, ‘No. No, we’re not doing it. Three days ago I thought my son was going to die, so no, you can’t take my son for a week.’ ” But Armstrong changed her mind; she realized staff members at Camp New Day had decades of experience with the chronic illness versus the short time she had managed Taygen’s diabetes. “We knew very little at that point in time,” she said. “We were leaving him with counselors and staff who know the disease inside and out.”

At camp, “it was really cool whenever you’re with everybody who understands,” Taygen said. “No one treats you like you’re not normal.”

Christian Clay, a camper-turned-counselor, said his mom and doctor talked him into going to the children’s camp. “I say ‘talked me into it,’ but I got volun-told to go,” he said.

Clay, who was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes in 2011, has attended camp seven times so far. “I enjoy the happiness I can feel from camp — being able to get out of my environment and learn something new and get to see some of my friends.”

Camp volunteering is tiring, Clay said, but helping others with diabetes is worthwhile. “Some people call it a disease; I call it a challenge,” he said. “I can show them I have the same challenge they do, and it does get easier over time.”

At the end of 2018, the Crouch Foundation of Amarillo donated a 640-acre ranch bordering Palo Duro Canyon and $500,000 to the Diabetes Foundation of the High Plains. In Ann Crouch’s handwritten will, she wanted to honor her son and husband, who both died of complications from diabetes. Lunsford said the nonprofit will design a new facility specifically for medical and special needs camps.

“I’m really excited,” Lunsford said. “We always dreamed of being able to build something.”

Dr. Alison Lunsford talks to a patient’s mother about blood sugar levels. Photo by Ralph Duke

Lunsford said it will be a lot of work, but with the help of skilled community members, she hopes the camp will be fully operational in two or three years.

Parents involved in the foundation care more about helping everyone versus the “What can you do for my kid?” mentality, she said.

“It makes it easier for me to do my job and to help take care of these kids,” Lunsford said. “We’ve been able to see a whole lot of great development in the community — awareness about diabetes. We’ve been able to support these kids a whole lot more.”

Children learn to administer their first shot and change their pump site at camp. Lunsford said kids will jump out of the swimming pool to compare pump sites. “It’s like positive peer pressure.”

At camp, all children learn healthy eating habits, and the older children learn about things to consider when they’re adults, such as insurance and drinking alcohol as a diabetic.

Initial goals of the foundation were to help patients who needed supplies, guide new diagnoses and connect families.

In the five years the foundation has operated, Lunsford has doubled the number of kids who attend camp by extending and splitting age groups and providing scholarships. Hiring a psychologist and a research nurse to help with her practice were also significant milestones.

“We had a few small things that we wanted to do and see where it took us,” Lunsford said. “It’s just taken off. I didn’t really envision how successful the fundraisers have been and how much we’ve been able to accomplish. It all exceeded my expectations.”

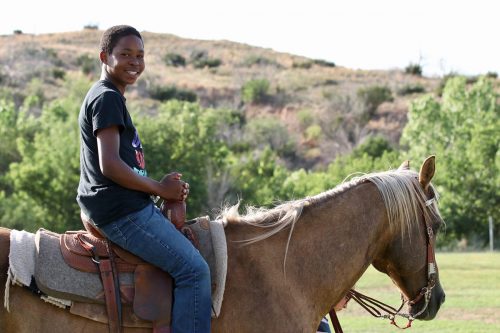

Avery and Owen lead a horse at Camp New Day in 2018. Campers say no one stares or is treated differently when it comes to diabetes management. Courtesy of Alison Lunsford/Diabetes Foundation of the High Plains

Camp New Day, which does not turn children away based on financial need, is just one aspect of the foundation. Lunsford said the nonprofit focuses not only on children with diabetes but also on their parents. “These parents live day in and day out with exhaustion,” she said.

Events such as an evening at a trampoline park are one way for kids to connect with other kids like themselves, as well as for parents to connect with other parents dealing with the same situations. Parents need a night out just as much as the kids, Lunsford said, and they can use the opportunity to learn the ropes from one another.

The foundation hosts five or six events each year. It also helps fund a diabetes research nurse at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center and offers aid to alleviate the sudden lifestyle changes that come with a diabetes diagnosis, such as providing grocery store gift cards to offset the cost of buying different foods and gas vouchers for long drives to the hospital.

“I have patients who have to drive three or four hours one way to get here, and your lower-income families just can’t do it,” Lunsford said. “We don’t have public transport — I can’t just send you a taxi.”

“I think Dr. Lunsford is a very good role model,” Taygen said. “She’s very kind, nice and helpful.”

At Taygen’s school in White Deer, Texas, about 40 miles northeast of Amarillo, only two other students have diabetes. Classmates are wary of the Dexcom continuous glucose monitor in the boy’s arm, so they don’t roughhouse with him like they do with other kids.

“They used to treat me like everybody else, but now they act like I’m a completely different person — like I’m breakable,” said Taygen, whose confident voice started quivering until he stepped away to compose himself.

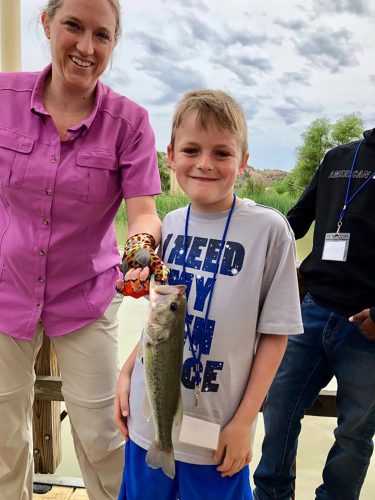

At Camp New Day, campers with diabetes like Malachi, 12, enjoy activities such as fishing, horseback riding and swimming. Courtesy of Alison Lunsford/Diabetes Foundation of the High Plains

Lunsford said children with diabetes in the Texas Panhandle are frequently the only student in their school — or whole community — to have the disease. “Kids who have chronic diseases frequently suffer from depression and social isolation,” she said. “They feel kind of ostracized or different. They start not taking care of themselves because they feel like they want to hide it.”

Facing a barrage of questions is another challenge. “A lot of our kids deal with it day in and day out at school or a friend’s birthday party,” Lunsford said. “People just look at them: ‘Why are you sticking yourself with a needle? What are you doing? I can’t believe you do that. That looks like it hurts.’

“That gets really old, so when they’re around a bunch of kids with diabetes, nobody asks those questions,” Lunsford said. “Nobody looks at you funny. Nobody says anything. For them, that’s every bit of what they need.”

Taygen uses his condition as a way to educate others. When people ask him questions, he answers. “It gives me a chance to teach someone something new.”

One day at school, Taygen noticed one of the adults was exhibiting symptoms of low blood sugar. He helped her test her levels, and he was right.

Dr. Alison Lunsford holds a fish Taygen caught at camp in 2018. Photo courtesy of Alison Lunsford/Diabetes Foundation of the High Plains

Or sometimes he jokes. Once when someone pointed at his glucose monitor, he responded: “The aliens did it.”

Though it’s constantly on their minds, for the Armstrong family, managing Taygen’s diabetes is just part of the daily routine.

Taygen’s Dexcom monitor communicates his blood sugar levels with an app his parents have on their phones. An alarm goes off if those numbers teeter out of a set range. Even with this monitor, his mother still worries, especially at night.

“I’m still waking up and checking the app,” Armstrong said. “I’ll watch trends and sit there and stay up for hours making sure he doesn’t drop. I don’t think that will ever go away.”

After senior camp, Taygen said, he wants to come back as a camp counselor. “I can interact with the kids. I can relate, so if they’re ever having trouble, I can talk to them about my experiences,” he said. “You can help them get through if they’re out there having a rough day — help them out and find the joy.”

Clearing hurdles and grappling with diabetes will always be ongoing. Now two years after his diagnosis, Taygen doesn’t let anything get in his way. He has even tested his blood atop a horse.

“I have a disease; the disease does not have me,” Taygen said. “I know that diabetes cannot stop me.”

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related reading:

Features

Dr. Brandon Pomeroy Helps the Kansas City Homeless

The physician is a key part of Care Beyond the Boulevard and frequently travels to Uganda, Mali and India for surgical trips.

Features

Dr. Wendy Bonnell Cares for Kids at Ruth’s Place Clinic

The pediatrician considers numerous determinants of health in her practice at the Granbury, Texas, nonprofit.

Alumni, Features

Dr. J Mack Slaughter Focuses on Healing the Spirit

The emergency room physician started Music Meets Medicine to give children with long-term illnesses a creative escape.