Curator Brings Discovery to Smithsonian as NASA Considers Mars

Space historian Valerie Neal shares stories from shuttle era.

Valerie Neal ’71 is behind one of the biggest collecting coups of the Space Age. Her star acquisition arrived on April 19, 2012 — feted by opera singer Denyce Graves and a stirring speech from legendary astronaut John Glenn. The space shuttle Discovery — the world’s most traveled spaceship — rolled into the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

“She is the person most responsible for us receiving Discovery, the most experienced of all the shuttles,” said Gen. J.R. “Jack” Dailey, who retired in January 2018 as the longest-serving director of the museum. “It may sound like that was a foregone conclusion, which was not the case at all. The competition [from other museums] was fierce.”

Discovery flew a record-breaking 39 missions in its 27-year history. Among its “firsts,” the shuttle sent into orbit the Hubble Space Telescope, whose mind-blowing images of faraway galaxies have illuminated our view of the universe. Discovery also ferried huge payloads from our planet to help build the International Space Station, where people have been living and working since 2000. Much of their research is paving the way for a return to the moon and — in NASA’s plans for the 2030s and beyond — a human presence on Mars.

Gritty Glory

The Smithsonian’s welcome for Discovery followed a dazzling flyover in the nation’s capital, with the orbiter riding piggyback on a Boeing 747. As a curator for the museum, Neal orchestrated the event.

“Her determination and negotiating ability carried the day,” Dailey said of Neal’s role in the acquisition of Discovery. “Its arrival was one of the major events for this region, which has many, but Discovery stole the show.”

Today the iconic orbiter is on display in all its gritty glory — one of the Smithsonian’s most popular exhibits.

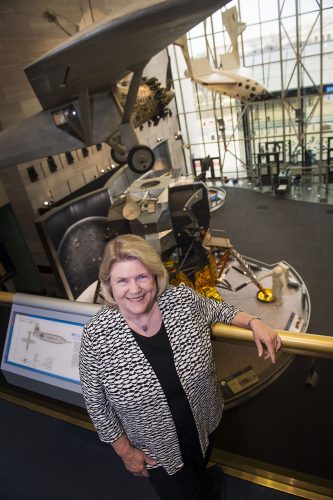

Valerie Neal with the Boeing Milestones of Flight exhibit, featuring the Spirit of St. Louis airplane, the Apollo LM-2 moon lander and the privately developed SpaceShipOne. Photo by Lisa Helfert

“It has streaks on the black tiles that are underneath — streaks of white almost like chalk where you can see how it came back into the atmosphere,” said Neal, who chairs the museum’s Space History Department. “Some people ask, ‘Well, are you going to clean it up, repaint it or something to make it look pristine?’ And we say, ‘No, because it flew in space 39 times and it needs to look like it flew in space 39 times. That’s the whole point of a reusable vehicle.’ ”

One astronaut takes that storied history to heart. “What I really appreciate about Valerie is that she was trying to personalize the human aspect of Discovery,” said John “Danny” Olivas, a retired NASA astronaut who logged 11 million miles in space. “A lot of people see it as a machine, but for those of us who flew on Discovery, it meant far more to us. It was our safe passage to and from space. Discovery was a great bird.”

At Neal’s request, Olivas gave the Smithsonian his Lucchese cowboy boots, custom-made in his hometown of El Paso, Texas, and embroidered with the Discovery STS-128 mission patch.

“It was kind of related to my identity growing up in West Texas,” said Olivas, who flew on two shuttle missions (aboard Atlantis and Discovery) and performed the first repair of a shuttle in orbit. “I grew up wearing cowboy boots, and so when I flew in space, that was going to be my gift to myself — a way of feeling like I accomplished a thing I set out to do.”

The boots are being prepped to go on display — one of more than 1,900 artifacts at the Smithsonian that Neal oversees from the space shuttle and International Space Station programs.

Enduring Influence

A TCU honors alumna in history and English, Neal brings the story of contemporary spaceflight alive for the nearly 9 million people who visit the National Air and Space Museum each year, making it America’s most visited museum.

The national collection of spaceflight treasures includes SpaceShipOne, the first privately built manned rocket, and the first Imax camera flown in space.

Planning future exhibits, Neal and her fellow museum curators are talking to private space exploration firms, including SpaceX (the brainchild of Tesla mogul Elon Musk) and Blue Origin (founded by Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos). Their reusable rockets are part of a more audacious plan: making humans an interplanetary species, where ordinary people become tourists in space or settle on Mars.

“That higher-order abstract thinking prepared me to go out in the world and feel confident that I could learn about anything — but more importantly, that I could learn [and] think about anything.”

Valerie Neal

“We have already been working with SpaceX and Blue Origin. We will probably approach Virgin Galactic,” Neal said. “There are some engines and devices that we have our eyes on. We just haven’t been able to spring anything loose yet because it’s all needed, but we’re laying the groundwork for that.”

Neal’s influence can be felt in major exhibits such as “Moving Beyond Earth,” which lets visitors “equip” a space station module or see the flight suit worn by American businessman Dennis Tito, the first tourist in space. She has consulted on Smithsonian documentaries and Imax space movies and recently served as an expert lecturer during a tour of the Northern Lights in Iceland.

Neal also vets retail products from merchants who are eager to win the Smithsonian stamp of approval. “Particularly with the Apollo 50th anniversary coming, we’re looking at a lot of toys, water bottles, coffee mugs . . .” she said. “Sometimes we reject items because they just aren’t appropriate or they’re misleading.”

In an age that has produced three female space shuttle pilots and two female commanders of the International Space Station, sexist products do not make the cut. “A girl’s shirt might say ‘Astronaut Cutie’ while a boy’s might say ‘Spaceship Commander,’ so we try to watch for that,” Neal said.

An Era of Triumph and Tragedy

The museum presents the space shuttle era without the romanticized, pioneer framework of the Apollo era and its six lunar landings.

Instead, the shuttle story traces 30 years of living and working in space (1981-2011) — “a new idea of spaceflight based on routine access to orbit for practical work,” Neal writes in her latest book, Spaceflight in the Shuttle Era and Beyond: Redefining Humanity’s Purpose in Space (Yale University Press, 2017).

The Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum bookstore displays copies of books by Valerie Neal. Photo by Lisa Helfert

It’s a story that produced 133 successful missions and two horrific losses — the Challenger and Columbia tragedies that claimed the lives of 14 astronauts. To honor the fallen, Neal worked closely with the families of the crews. They gave their blessing for a remembrance “as long as it wasn’t morbid, as long as it was respectful,” she said. “That was our intention all along.”

There is no shrine; the museum lays out the facts of those missions and acknowledges the inherent risk of human spaceflight. “We treat them as tragedies that were avoidable,” Neal said. “What was the technical flaw that led to the tragedy and what was the human flaw that led to it? It had to do with managerial decisions and taking shortcuts and not practicing good, sound safety practices in engineering. It was true for both Challenger and Columbia.”

America’s outpouring of sorrow also is recognized. The mementos displayed include a flag quilt — customized for each Challenger crew family by strangers wanting to offer solace. “Quilting circles all around the country sent little lap quilts to the astronauts’ families,” Neal said. “They were inundated with teddy bears, too. It was so touching in both cases that ordinary citizens wanted to give something that would be of comfort.”

Reflecting on the Challenger tragedy, Neal said she received a postcard in the mail on Jan. 28, 1986 — the same day the shuttle broke apart after liftoff, killing all seven crew members. The postcard was from NASA, acknowledging that the agency had received Neal’s application for its first “Journalist in Space” program (broadcast icon Walter Cronkite also applied). The program never happened.

While Discovery would return America’s shuttle missions to success — spending a total of 365 days in space until its last flight in 2011 — the Challenger and Columbia tragedies cast a deep shadow. “Its two losses put the idea of routine spaceflight under scrutiny,” Neal observes in her book. “What was not publicly expressed before 1986 is now commonly held: that the shuttle was inherently an experimental vehicle that operated on the margins of what was technically achievable.”

Lessons for Deep Space

Getting to Mars and beyond is no longer in the realm of science fiction. NASA plans to use its Orion capsule to send humans to a near-Earth asteroid by 2025. Then it’s on to Mars (via a way station near the moon) in the 2030s.

The agency has an exhilarant catchphrase for America’s next giant leap: “The first humans who will step foot on Mars are walking the Earth today.”

“It may be a prelude to a really exciting time,” Neal said.

Indeed, Musk ignited a cult frenzy when livestreaming his Falcon 9 rocket launches for SpaceX. Blue Origin touted seats for six aboard its New Shepard capsule, designed to take paying tourists into space. The reusable rocket is “large enough for you to float freely and turn weightless somersaults,” according to Blue Origin’s website.

“She shined a brighter light on cultural and political dynamics that shaped my astronaut world.”

Kathryn D. Sullivan, astronaut

What we’ve learned about human spaceflight since the first shuttle flight in 1981 lights the path for private astronauts and deep space travel, Neal said.

“I think the space shuttle era taught us a couple of really valuable lessons. One is that to a certain extent, you can make spaceflight routine,” Neal said. “We approached the closest thing to routine spaceflight that’s ever been experienced on this planet. It just happened to be harder than we thought and more expensive than we thought.”

A sobering lesson from the shuttle era, Neal said, “is that it’s hard to sustain interest and support for spaceflight if it’s just in Earth’s orbit.”

Many people are surprised to learn that Americans have been in space almost continually since 1981 — and orbiting 250 miles above us on the International Space Station since 2000. “They often seem kind of underwhelmed by it,” she said. “Like, ‘Oh, I didn’t know that was happening.’ ”

Role in Research

Space as a laboratory is a key part of the shuttle legacy. Using astronauts as test subjects, scientists are investigating the scope of cosmic dangers — including how space radiation affects lifetime cancer risk and the ways microgravity alters blood chemistry and a human’s ability to function.

In the September 2017 issue of Smithsonian Magazine, astronaut Scott Kelly gives a riveting account of his physical misery and struggle to walk again after coming home from a full year in space — a journey he said he does not regret.

“If you were to live an appreciable portion of your life away from Earth, what would your prospects be when you came back for having the immunities and basic biochemistry that you need to stay healthy?” Neal said, describing questions scientists might examine. “What does this mean for even longer-term spaceflight? And is it really going to be feasible for humans to go far out, stay awhile and then come back?”

The increasingly elaborate work done in space — both in scientific research on the International Space Station and repairs to the Hubble Space Telescope, for example — is another payoff from the shuttle era. “They have done repair tasks in space that are comparable in the mechanical world maybe to brain surgery in the medical world,” Neal said. “It really expanded the range of work that astronauts can now confidently and competently do in weightlessness.”

Opening spaceflight to a more diverse astronaut corps also started with the shuttle, Neal said. “Firsts” of the era include the flights of Sally Ride, the first American woman in space; Guion “Guy” Bluford, first African-American in space; Ellen Ochoa, first Hispanic woman in space; and Mae Jemison, first African-American woman in space.

“The shuttle democratized spaceflight,” Neal said. “Because of its missions, it needed crews that represented a wider range of talents and abilities than simply piloting. And there was a much bigger pool of candidates out there who were scientists and engineers. The era certainly proved that a diverse astronaut corps is reasonable and wholly capable.”

Insatiably Curious

Neal’s expertise as a space shuttle scholar has not gone unnoticed. Former NASA astronaut Kathryn D. Sullivan, the first American woman to do a spacewalk, said Neal may be the one person who knows the shuttle program better than its crews.

At the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, curator and chair of the Space History Department Valerie Neal ’71 signs copies of her books. Photo by Lisa Helfert

“Valerie may not have our operating mastery, but she knows a lot about the technical history of the shuttles — often fascinating tidbits that I never knew — and also has a rich understanding of how it fits into U.S. space-faring history and American culture,” Sullivan said. “She shined a brighter light on cultural and political dynamics that shaped my astronaut world.”

It was at TCU that Neal, an ebullient student from Hot Springs, Arkansas, savored the culture before her: the museums of Fort Worth, exposure to visiting artists on campus, a weekend study spot in the Fort Worth Botanic Garden. The daughter of a postal worker and a homemaker, Neal was the first from her family to attend college.

“She was insatiably curious about any and all of the subject matter, and she openly [but not uncritically] looked to her teachers for guidance and mentoring,” said Fred Erisman, the Lorraine Sherley Professor of Literature Emeritus at TCU.

Erisman said Neal was already a good writer when she arrived on campus. Now, more than 40 years later, “the books that she has produced have only grown in depth and sophistication,” he said.

Neal credits her honors seminars — especially courses on the nature of values, society and knowledge — with building analytical brainpower. “You weren’t thinking about concrete facts, you were thinking about ideas and arguments and questions,” she said. “That higher-order abstract thinking prepared me to go out in the world and feel confident that I could learn about anything — but more importantly, that I could learn [and] think about anything.”

As a museum curator and manager, Neal often pictures a multifaceted crystal when tackling a problem. “I try to turn that crystal around and around and look at it from different perspectives until I get a sense of the full nature of that problem — and what the different perspectives and solutions might be,” she said. “I think that arose out of taking those more abstract courses at TCU.”

At the urging of her professors, Neal advanced her education — earning a master’s degree in American Studies from the University of Southern California and a doctorate in American Studies from the University of Minnesota.

She honed her space smarts as a writer and editor for NASA publications at the Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. One of the job perks: Neal became a certified “utility diver,” helping astronauts with test prep in the center’s 40-foot dive tank. “Underwater training is dress rehearsal for spaceflight,” Neal said.

Mantra for Life

When Neal joined the Smithsonian in 1989, she navigated not only a new town and new job but also single motherhood. Her son had just turned 11 when Neal’s husband died at 45 after a battle with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (former President Bill Clinton, a childhood friend, attended the funeral; he was governor of Arkansas at the time).

Valerie Neal talks about a display of objects from NASA space shuttle missions. The display is part of the museum’s Moving Beyond Earth exhibit. Photo by Lisa Helfert

“She was at all my games, engaged with my academic life and always co-creating opportunities for enrichment with me,” said Neal’s son, Bryan Guido Hassin, co-founder and CEO of Smart Office Energy Solutions, a clean-technology energy company. “She never complained about being overburdened and really seemed to love both her work and family life.”

Hassin recalled growing up in the shadow of the shuttle era — attending launches with his mom, soaking up the Smithsonian’s riches and once flying to Hot Springs courtesy of an astronaut.

His mother’s vanity license plate, WHRNEXT, “became a mantra of hers and ours: Where should we go next?” Hassin said. “Where should we explore?”

“Mom also instilled in me a strong moral compass and a responsibility to help others,” he said. “I’m sure both faith and ethics steered her toward TCU.”

Calling TCU a “golden period” in her life, Neal hinted that she would love to return someday, perhaps as an adjunct faculty member. “It was such a hospitable and welcoming place,” she said. “Definitely the best part of my education, the most influential. I learned more and grew more than I imagined I would.”

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related reading:

Features

Smithsonian Curator Chronicles Remarkable Life of Sally Ride

The collection highlights the achievements of the first American woman in space.

Features

A Closer Look: Books by Valerie Neal

The Smithsonian curator’s latest nonfiction book is Spaceflight in the Shuttle Era and Beyond.

Research + Discovery

Eclipsing Research

TCU astronomer Kat Barger shines a light on the Milky Way’s origins.