March 24, 2020

Would Increasing Gasoline Tax Help Reduce Climate Change?

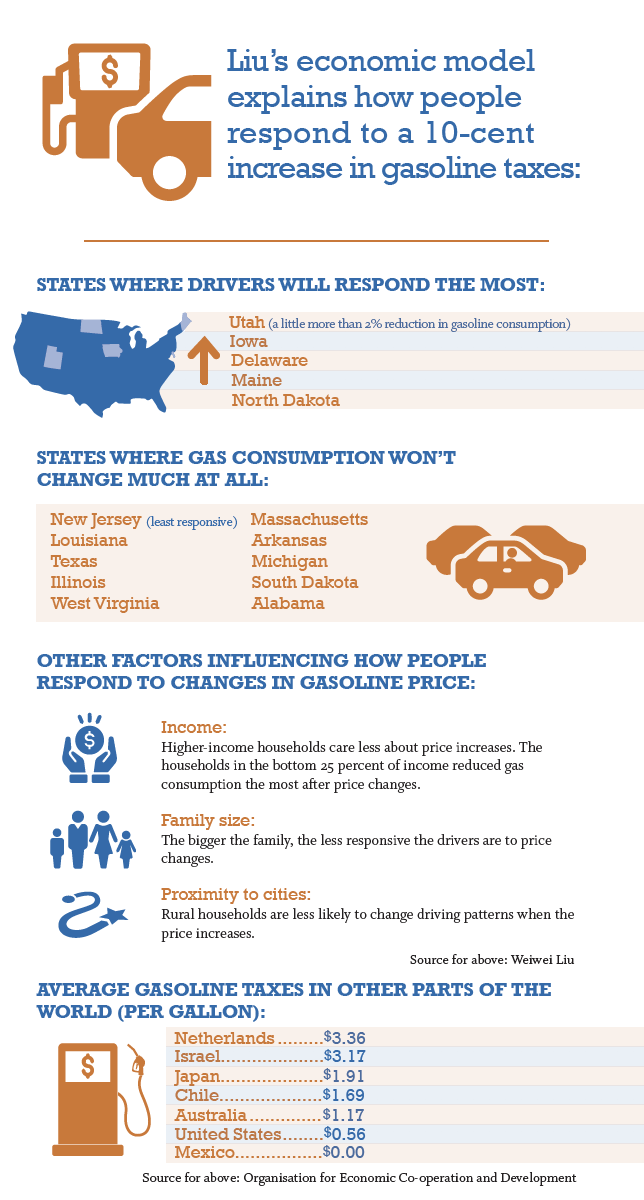

Weiwei Liu says that for higher gasoline taxes to be an effective method of curbing climate change, they need to be customized by region and even individual.

March 24, 2020

Would Increasing Gasoline Tax Help Reduce Climate Change?

Weiwei Liu says that for higher gasoline taxes to be an effective method of curbing climate change, they need to be customized by region and even individual.

Getting a handle on a warming planet will require a group effort, said Weiwei Liu, assistant professor of economics at TCU. Automobile use, in particular, must be reimagined because it plays a key role in driving up global temperatures. The transportation sector accounts for about 29 percent of the world’s carbon emissions, and personal vehicles are responsible for more than half of those emissions.

Graphic by Mike del Vechio

To encourage more sustainable transportation habits, economists recommend higher gasoline taxes, which in theory should reduce fuel consumption, and higher fuel-efficiency requirements for new cars. In 2019, federal gasoline tax in the United States averaged about 50 cents per gallon. The Environmental Protection Agency and National Highway Traffic Safety Administration have mandated new cars deliver 55 miles-per-gallon efficiency by 2025 (though the Trump administration is attempting to cut the requirements to 37 miles per gallon).

But the well-considered policy measures have not delivered the expected reduction in domestic gasoline consumption. The reasons are twofold. For one, “When something becomes really cheap, we tend to abuse it,” Liu said. “If your car is really efficient, you drive more, and you go on more trips.” For two, different people also have different options in responding to tax-enhanced gasoline prices.

In the past, economists have estimated population-wide reactions to gasoline tax changes, but Liu said the one-size-fits-all approach is not realistic. She used what’s called a semiparametric model, a complex economic equation that accounts for individual differences. To crunch the more personal numbers, Liu used the Consumer Expenditure Survey published by the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics. It reports income along with a range of demographic information.

Her findings might improve estimates of how fuel-efficiency regulations and hikes in gas tax affect consumption and thus the climate. In addition, Liu said her model might incentivize people to hang up the nozzle, but only if taxes can be variable based on region, income and family size, for starters. “If our goal is in the long run to reduce gas consumption and to reduce carbon emissions, then customizing the tax rate might work in the future.”

Graphic by Mike del Vechio

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related reading:

Research + Discovery

Climate Change? Have Another Cup of Coffee

Omar Harvey studies novel ways to capture and store carbon dioxide.

Alumni, Features

Master of Liberal Arts Program Encourages Critical Thinking

The degree gives graduate students a chance to take lifelong learning and leading a step beyond.

Campus News: Alma Matters, Research + Discovery

Factoring Humanity and Happiness into Economic Calculations

In a Q&A, Rob Garnett, professor of economics, honors professor of social sciences and associate dean in the John V. Roach Honors College, combines economics with happiness.