TCU secured its second national championship of the 1930s with a 15-7 victory over Carnegie Tech in the 1939 Sugar Bowl. Courtesy of the University of Texas at Arlington Libraries Special Collections

Football Powerhouse

The 1930s were a golden age for TCU Football under legendary coach Dutch Meyer.

The man who helped bring national attention to TCU was the perfect fit for a transient football program and university.

An 11-year-old Leo “Dutch” Meyer served as a waterboy for the 1909 Horned Frog football team, the last to play a season in Waco, Texas, before TCU relocated to Fort Worth.

He followed the Frogs to their new home, becoming a student-athlete in 1916 as the university and the football team were still finding their footing. World War I took him from TCU for a few years, but he returned to graduate in 1922.

Meyer picked up 11 varsity letters in three sports, then coached the freshman football and baseball teams. He was Mr. TCU if there ever were one, and he would build the football program as the university grew in a Texas city that was beginning to evolve beyond its cow-town roots.

The 1938 Horned Frogs were so good, “They never had a real scare in their 10-game schedule and a Sugar Bowl victory over Carnegie Tech,” wrote Dan Jenkins in Sports Illustrated in 1981. Courtesy of TCU Library Special Collections

If the name “TCU is familiar to the multitudes from Maine to California, it is so, doubtless, by the reason of the fame of the Horned Frogs football team,” J. Willard Ridings, a professor of journalism who served as the unofficial publicist for those Frogs teams, wrote some 80 years ago.

Lore has it that Meyer was as tough as the times were in the 1930s, with the nickname Old Iron Pants and the famous catchphrase “Fight ’em ’til hell freezes over, then fight ’em on the ice.” But Meyer was also a football genius.

He implemented a revolutionary offense that passed first to set up the run. Meyer knew that a football team needed to “have the hosses to win the race,” and he found two quarterbacks who would lead the best Frogs teams in program history.

The 1935 and 1938 teams, led by Sam Baugh ’37 and Davey O’Brien ’39, are the only two in program history to capture the national title. They forever changed football with their passing strategies and became the first great gridiron squads west of the Mississippi.

By the end of the 1930s, TCU had one of the preeminent football programs in the country, despite an enrollment of only 725 at the beginning of the surge.

Modern teams in 2010 and 2022, guided by coaches Gary Patterson and Sonny Dykes and led on the field by quarterbacks Andy Dalton ’10 and Max Duggan ’22, were great. Each finished the season ranked No. 2 in the country and with a school-record 13 victories.

But the 1935 and 1938 teams, with a trailblazing coach and two all-time college quarterback greats, helped put tiny TCU and Fort Worth on the map during the golden age of TCU Football.

“They were the team in the nation for all intents and purposes, winning two national titles in a four-year span,” said Denis Crawford, a historian and curator at the College Football Hall of Fame in Atlanta. The 1930s Frogs “really raised the profile of all Texas football.”

Dutch and Sam

The first game in TCU history was played in 1896 against Toby’s Business College, and it was a win. The 1904 Frogs scored only five points but managed to go 1-4-1 thanks to a tie and a win over Baylor that might have saved the program. Until that victory, TCU hadn’t won a game since the 1901 finale, going 0-16-2, and support was waning with the Board of Trustees even though football was popular with the students.

From 1896 to 1922, TCU had 17 head coaches. Matty Bell coached from 1923 to 1928 and oversaw the transition from the Texas Intercollegiate Athletic Association to the Southwest Conference before he left for conference rival Texas A&M.

His replacement, Francis Schmidt, led the Frogs to a 47-5-5 record in five seasons and coached the first two conference champions in program history. That success captured the attention of Ohio State University, which whisked Schmidt away.

The replacement was already on campus, and so was the first of two stellar quarterbacks who would take TCU to its greatest heights, with an assist from the University of Texas.

“Babe Ruth had a home-run statistic that sometimes was more than an entire team combined. Sammy Baugh during this ’34 to ’36 phase is throwing the ball more often for more yards and more touchdowns than some teams managed to do.”

Denis Crawford, College Football Hall of Fame historian/curator

The brass and boosters at Texas thought so much of baseball coach Billy Disch that they named the Longhorns’ ballpark after him. TCU fans should like him, too.

Disch had his hands on a strong-armed third baseman from Sweetwater High School in West Texas who wanted to play baseball at Texas. He also wanted to play football, and Disch would not allow it.

That, the legend goes, is how Sam Baugh ended up at TCU.

Meyer was the Frogs’ baseball coach in 1933. He was also the freshman football coach, and he was more than willing to let Baugh play both sports. Basketball, too.

Meyer was promoted after Schmidt departed, and the 1934 season would be the first of Meyer’s 19 seasons at TCU’s helm. That year also marked the first of three varsity seasons for Baugh, who would win 29 games from 1934 to 1936.

Meyer called Baugh the greatest athlete he ever coached. The quarterback had the speed and moves of a running back, which came in handy in Meyer’s double-wing offense that spread the field and featured short passes to set up the run game.

Baugh threw for a then school-record 883 yards in 1934, when TCU went 8-4. He amassed an NCAA-leading 1,241 yards through the air in 1935, when TCU opened the season 10-0. His passing numbers were unprecedented.

“It was almost like Babe Ruth and the home run,” Crawford said. “Babe Ruth had a home-run statistic that sometimes was more than an entire team combined. Sammy Baugh during this ’34 to ’36 phase is throwing the ball more often for more yards and more touchdowns than some teams managed to do.”

Baugh was also a safety and punter in an era when players needed to play offense and defense, displaying a toughness he exuded off the field as well. He did odd jobs such as cleaning a music room to help pay the balance of his tuition while also courting his future wife, Edmonia Smith ’38.

“He was a rough-edged, tobacco-chewing country boy but likable and friendly and never met a four-letter word he didn’t like,” legendary sportswriter Dan Jenkins ’53, a Fort Worth native, said after Baugh’s death in 2008.

Standing in the Horned Frogs’ way of a perfect ’35 season was Southern Methodist University, and the rivalry game that season at TCU was heralded as the Game of the Century by famed sportswriter Grantland Rice. The Mustangs were also 10-0 when they made the trip from Dallas.

Rice came to town to cover the game for the New York Sun and chronicled what turned into a 20-14 SMU win, the Frogs’ only loss of the season. What he wrote about Baugh brought national acclaim to the TCU star: “Mr. Slingin’ Samuel Baugh can chunk that cabbage,” Rice wrote. “He could murder a fly on a fence with the snout of that missile from any distance from a yard to 50.”

TCU earned a spot in the Sugar Bowl against Louisiana State University, a game remembered for its score: 3-2. Baugh contributed more as TCU’s punter, with 14 punts, than he did as a passer on the sloppy, muddy field at Tulane Stadium, but the Frogs won to run their record to 12-1.

SMU lost in the Rose Bowl and also finished 12-1.

Back then, the NCAA recognized 13 selectors of the national champion. A team could be picked by only one of the 13 and still be considered a champion.

That’s what happened to TCU.

Paul Williamson, a member of the Sugar Bowl committee, was a scientist who devised a formula that he believed calculated the best team in football, Crawford said. The NCAA recognized his Williamson System, which spit out the Frogs at No. 1 for the program’s first title.

The Frogs finished 9-2-2 in Baugh’s senior campaign in 1936. They played in the Cotton Bowl for the first time and beat Marquette. It was time for a new challenge for Baugh, who became the first great professional passer with the NFL’s Washington franchise.

“All the coaches I had in the pros, I didn’t learn a damn thing from any of ’em compared with what Dutch Meyer taught me,” Baugh told the Washington Post. “Everybody loved to throw the long pass. But the point Dutch Meyer made was, ‘Look at what the short pass can do for you.’ You could throw it for 7 yards on first down, then run a play or two for a first down, do it all over again and control the ball. That way you could beat a better team.”

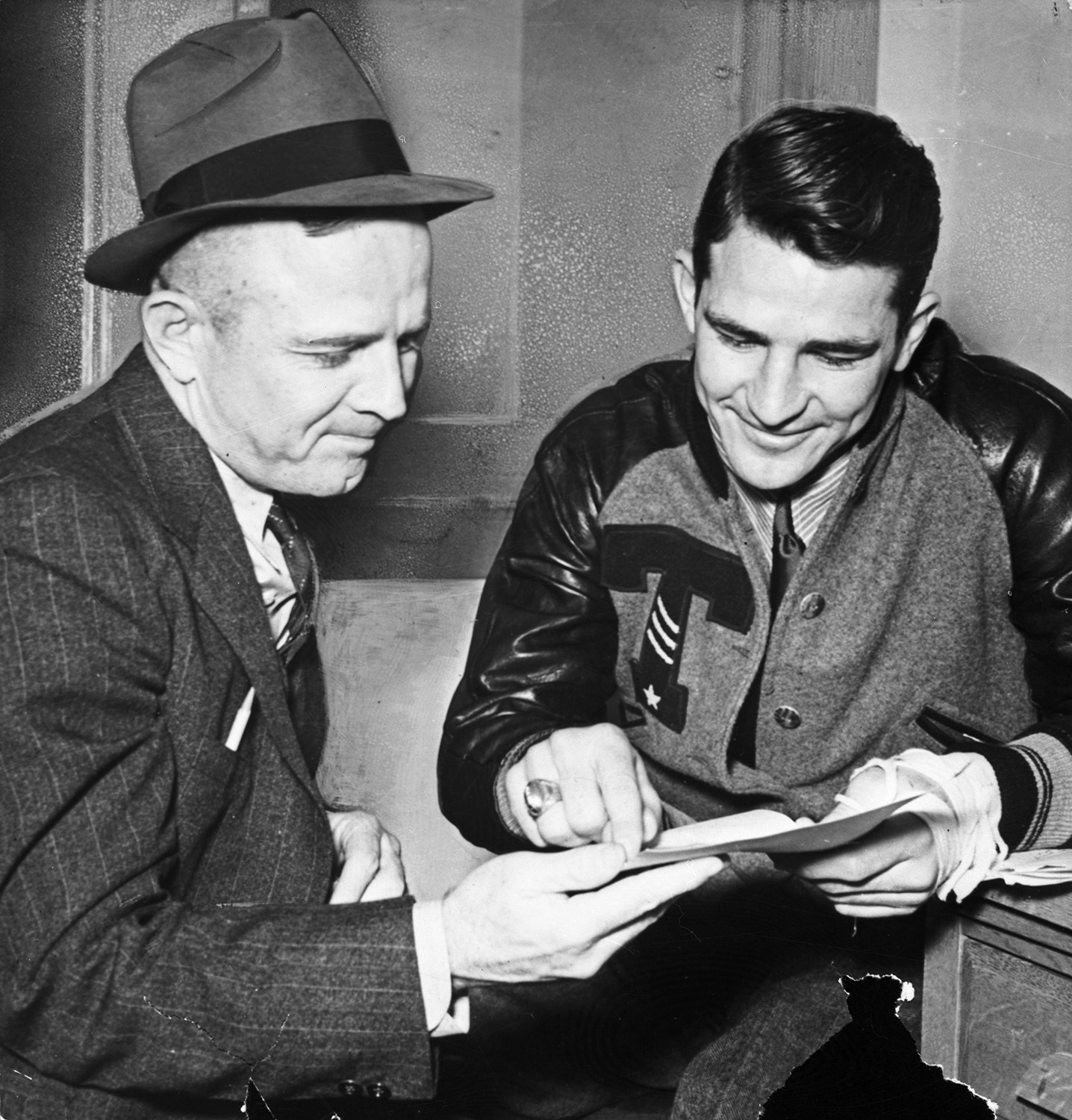

Legendary football coach Dutch Meyer, left, called quarterback Sam Baugh the greatest athlete he ever coached. The two led the Horned Frogs to their first national championship title. Courtesy of University of Texas at Arlington Special Libraries Collections

Baugh to O’Brien

Davey O’Brien watched history unfold as an underclassman during Baugh’s tenure, having been recruited by Meyer from Woodrow Wilson High School in Dallas.

O’Brien didn’t know his father well after his parents divorced when he was a toddler, and his mother raised him and his brother in the Lakewood area of Dallas with the help of her brother. His parents apparently were small in stature, as O’Brien weighed 120 pounds during his senior year of high school.

He would bulk up some at TCU, where he inherited the quarterback job in 1937.

“The Frogs were so good behind little Davey’s passing and running and ball-handling magic, they throttled everyone with ease. They never had a real scare in their 10-game schedule and a Sugar Bowl victory over Carnegie Tech. There was no drama.”

Dan Jenkins, in 1981 for Sports Illustrated

Meyer assembled a strong team that included O’Brien’s childhood friends I.B. Hale ’39 and Rusty Cowart ’40, who were raised in an orphanage behind O’Brien’s home. Hale became an All-America lineman. The team also featured Ki Aldrich ’39, an All-America center who would be the first selection in the 1939 NFL draft.

The Frogs had the talent to win big in 1938.

They opened with home wins over Centenary College and Arkansas before winning three straight on the road against Temple, Texas A&M and Marquette. TCU would later beat Baylor, Texas and SMU by a combined score of 87-20 en route to a 10-0 regular season. O’Brien threw for 1,457 yards and 19 touchdowns while also playing in the secondary and handling some kicking duties.

TCU staked its claim to the national title back at the Sugar Bowl, beating Carnegie Tech 15-7. O’Brien threw for a touchdown, kicked a key late-game field goal and intercepted a pass in TCU territory that clinched the game.

“The Frogs were so good behind little Davey’s passing and running and ball-handling magic, they throttled everyone with ease,” Jenkins wrote for Sports Illustrated in 1981. “They never had a real scare in their 10-game schedule and a Sugar Bowl victory over Carnegie Tech. There was no drama.”

O’Brien was the fourth player to win the Heisman Trophy and the first from a school that wasn’t along the East Coast. Eighty-three Heisman winners have followed, and O’Brien remains the smallest to ever win the award at 5-foot-7 and 151 pounds.

They didn’t call him Little Davey for nothing.

“He was a great athlete,” Crawford said. “Dutch Meyer said that he was not the passer that Sammy Baugh was, but he made up for it by being a tough son of the gun and by being able to call plays and being a true field general.”

Lasting effect

Meyer coached his last game in 1952. However, his fingerprints are still on today’s game.

“Dutch Meyer was way ahead of his time,” Dykes said. “Football in those days was kind of played all wadded up, almost like rugby. He had the great idea of spreading the field out and creating space. It just simplifies the game when you do that.”

Dykes said Meyer put the emphasis on the quarterback and his ability to read what the defense was doing. He wanted to spread the field for “short, sure and safe” passes that gave receivers a chance to move down the field.

“Dutch Meyer was way ahead of his time. Football in those days was kind of played all wadded up, almost like rugby. He had the great idea of spreading the field out and creating space. It just simplifies the game when you do that.”

TCU football coach Sonny Dykes

His offense was a double-wing system, which featured an empty backfield and five skill players spread outside the offensive tackles; it became known as the Meyer Spread.

“Meyer definitely helped to usher in the modern passing game,” Crawford said. “Before they even knew what yards after a catch was, that was what his offense was.”

Dykes’ offense, the Air Raid, largely does the same thing, and he said he wants TCU to be balanced between running and passing. The offense is at its best when it’s able to churn out yards on the ground, as the Frogs did last season with Duggan, Kendre Miller and Emari Demercado ’21 (MS ’22).

The threat of a Duggan pass to Quentin Johnston or Derius Davis ’22 helped create just enough of a delay for ball carriers to find room to roam. The threat of a run helped create just enough space for Duggan to complete a pass.

Offensive formations today that have no running backs in the backfield, called empty, were first used in college football by Meyer. He put his coaching philosophies into a 1952 book, Spread Formation Football, and variations of the plays drawn in it can be found in TCU’s playbook today.

“He had some great concepts,” Dykes said. “But if you look, you can see play after play after play is … no running back and five wide receivers.”

Duggan’s remarkable 2022 campaign led to a second-place finish in Heisman voting. He also became the first TCU player to win the Davey O’Brien Award, which is given annually by the Fort Worth-based Davey O’Brien Foundation to the nation’s best quarterback.

Baugh and O’Brien were among the nation’s best quarterbacks in the 1930s in Meyer’s pass-happy offense, and they put TCU football on the map while revolutionizing the game.

“That’s two of the best quarterbacks that ever played in high school and college football, and I think they both benefited greatly from playing in a wide-open offense,” Dykes said. “TCU football in a lot of ways was way ahead of its time.

“Dutch’s whole thing was make it about the quarterback and make it about the skill players. That was their niche, and it was a lot different than what anybody else was doing.”

Your comments are welcome

1 Comment

What color were the jerseys in 1936 and 1938. Deep purple or black? What was on the back of the jerseys? Did they have names or larger numbers?

Related reading:

Latest News, Sports: Riff Ram

Heart of a Horned Frog

Max Duggan’s determination has helped lead TCU to the finals of the College Football Playoff.

Sports: Riff Ram

Flashback to Freshman Football

Wogs players spent a year preparing to become full-fledged Frogs.

Features, Sports: Riff Ram

A Season to Remember

The Horned Frogs kick off the Sonny Dykes era with a magical run to the national championship game.