Addison Clark, seated center with a long beard, and his brother Randolph, seated at right, launched the college that became TCU in 1873 in Thorp Spring, Texas. Thirteen students attended class the first day. From the beginning, the institution offered equal education to men and women. TCU is now the longest continuously operating coeducational university west of the Mississippi River. Courtesy of TCU Library Special Collections

A Dream and a Prayer

Addison and Randolph Clark’s tiny coed Christian college on the prairie blossomed into TCU.

Farm-to-Market Road 4, known as the Lipan Highway, is one of those two-lane roads that traverse the rolling Texas countryside. The tranquil pathway seems far removed from modern urban life. Forty miles and a world away from TCU.

Just northwest of Granbury, Texas, the curving road arrives in Thorp Spring, an unassuming rural community named for Pleasant Thorp, a blacksmith and Texas Revolution veteran who attempted, unsuccessfully, to mold the area into a resort destination.

It was in Thorp Spring that brothers Addison and Randolph Clark, along with their father, Joseph, launched a small college with the intent of providing a classical Christian education. The school was part of Thorp’s grand design for the area, and he offered the Clarks generous terms for the purchase of a building and some land for $9,000 — equivalent to a little more than $200,000 in today’s currency.

That institution, AddRan Male and Female College, grew against long odds into Texas Christian University. The college survived financial hardships, a fire and two moves before the Clarks’ creation took root in Fort Worth in 1910.

Wild Texas

The Clark brothers were born in the uncertain, migratory times of the Republic of Texas. Hetty Clark, the family matriarch, gave birth to Addison in 1842 in the northeast part of the state near a town called Daingerfield. Randolph followed two years later a little to the south in Harrison County. The brothers were the first of Joseph and Hetty Clark’s 11 children.

Joseph Clark moved the family frequently, usually in search of better economic opportunities but also to avoid violence. In the 1840s, the Texas frontier was an unsafe environment with an expanding population; law enforcement was often inconsistent and wanting, and the Republic of Texas lacked the necessary resources to provide any sense of public safety.

Political rivalries at times devolved into disputes over land claims and fraud. One conflict escalated into gang warfare in East Texas, including in Nacogdoches County, where the young Clark family was then residing.

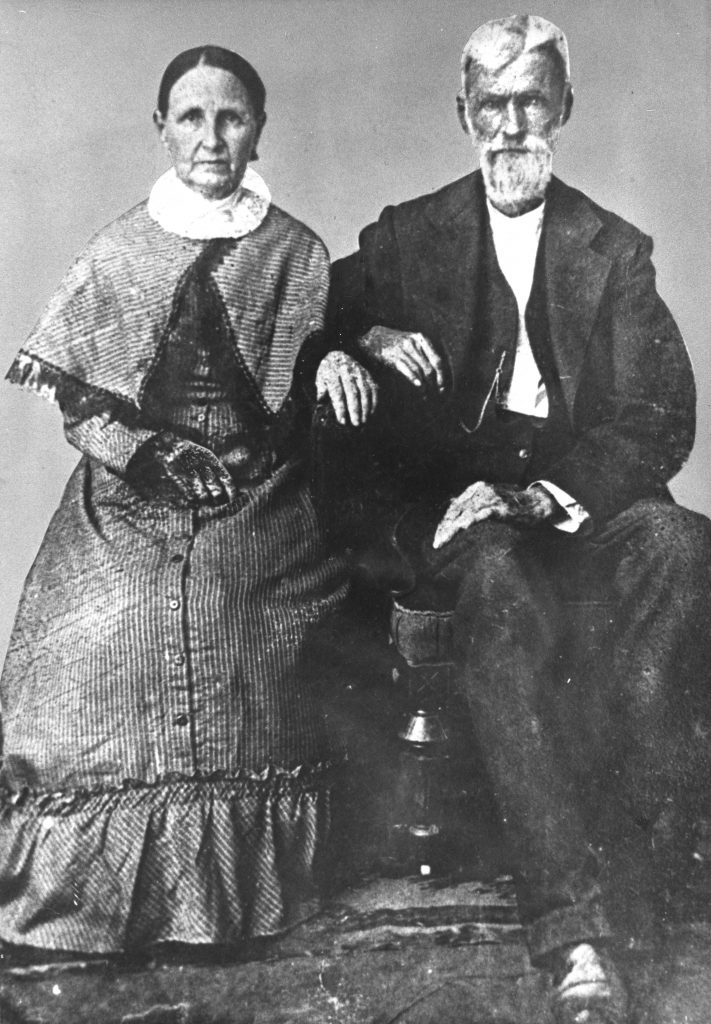

Hetty and Joseph Clark raised their 11 children — of which Addison and Randolph were the oldest — while moving around a fledgling Texas to find economic opportunity and avoid violence. Hetty was an educated woman who encouraged the scholarly pursuits of her offspring. Joseph became an ordained Disciples of Christ minister and later feuded with his sons over the matter of instrumental music during worship services. Courtesy of TCU Library Special Collections

When the feud claimed the life of a friend, Joseph packed up his family and left the area for parts farther north.

Such was the wild Texas into which Addison and Randolph were born.

Elementary education was scant in the frontier republic. Hetty was an educated woman, well-versed in the basics of writing, arithmetic, music and art. Having an erudite mother no doubt influenced Addison and Randolph Clark’s decision to educate men and women in the same classrooms, which would make AddRan the first continuously coeducational institution of higher learning west of the Mississippi River.

Strong, resilient women were a constant in the lives of the Clark brothers. At one point, both parents were absent from the homestead, with Hetty leaving to complete her education at the school run by her brother Benjamin DeSpain in Jackson, Louisiana, and Joseph traveling to Fannin County, where he received a license to practice law.

The absences left the Clark children in the care of their maternal grandmother, Rachel DeSpain. Widowed in 1825, DeSpain had made the dangerous trek from Alabama to Texas, then under Mexican rule, by wagon train in the mid-1830s. (For a short while, Davy Crockett had been their guide.)

Though DeSpain was illiterate, she believed in the importance of education, doing all she could to ensure the Clark brood was able to read and write from a young age. She also sought to instill in them the importance of good character. The Bible was used as teaching material for both objectives.

The Noise of War

Joseph Clark converted to his wife’s Disciples of Christ denomination sometime around Addison’s birth. Hetty’s family were followers of the Disciples; her maternal grandfather, Benjamin Lynn, was an early prominent adherent to the Restoration Movement from which the Disciples originated.

Joseph Clark’s Christian moral code did not lead him to question the tenets of Southern economics. To build family wealth, Joseph, like many Southerners, often relied on the labor of enslaved people.

When the Civil War was brewing, Addison, the eldest, dithered on whether to join the fight to maintain chattel slavery. His hesitancy had less to do with the morality of slavery than with his reluctance to participate in combat. The principal founder of the Disciples, Alexander Campbell, had been a dedicated pacifist, and Addison, who took his Christian faith seriously, agonized over the issue.

But many in the local congregation ended up abandoning Campbell’s pacifist teachings. In the end, Addison chose to join his neighbors. He enlisted in the Confederate service in 1862, a year after the hostilities began. Randolph wished to follow his brother into what he termed “the noise of war,” but he was not yet old enough to enlist.

When his big brother left to fight, Randolph stayed behind to help their father with the family’s successful mercantile business in Grayson County, which Joseph operated at a handsome profit during the war by selling grain, meat, sugar and other staples that were then in short supply.

Once he grew old enough for military service, Randolph felt the pressure to enlist. He never formally enlisted in the Confederate army, but in April 1864, he packed his horse and set off in search of his brother, finding him in Mansfield, Louisiana, where he became unofficially attached to Addison’s unit.

Nothing in the younger Clark’s life had prepared him for the horrors of war. He later described the conflict as “not a frolic, but murder, legalized by man,” though his unit saw action in only one battle, Jenkins Ferry.

Seeing the writing on the wall one month before Robert E. Lee’s April 9, 1865, surrender in Appomattox, Virginia, Randolph declared the Confederacy “no more than a memory.” That month the brothers returned to the Clark home in Hill County, where Joseph had moved the family during the war.

Into the Classroom

In summer 1865, Addison Clark became a professional educator, opening a school in Buchanan, Texas, just northwest of Cleburne. The school closed after one session, but Addison quickly opened another in nearby Alvarado; it also failed.

Addison clung to the idea of opening his own school, but he needed more experience as an educator and in the intricacies of running such a venture, including the financial aspects. And Randolph needed to make his way outside of the family home.

In 1866, both Clark brothers decided to advance their educations. The brothers chose Carlton College, the first Disciples of Christ school in Texas, in Grayson County, and for good measure brought their younger brother Josey along to begin his formal studies.

A statue of founders Addison and Randolph Clark, erected in 1993, sits on the east side of the TCU campus. Photo by Jeffrey McWhorter

The school’s proprietor, Charles Carlton, was a prominent Disciples educator who became the brothers’ mentor.

Randolph was in the early stages of his academic career and enrolled as a beginner student, as did Josey.

Addison was somewhat of an established scholar, having attended an academy in Palestine, Texas, for two years. He also had studied at an academy in Tennessee Colony, Texas, where he had excelled in mathematics, science and the classics. Addison’s aptitude prompted Carlton to offer him an instructor position while he continued his advanced studies.

There Addison met Sallie McQuigg, Carlton’s niece. The couple wed in January 1869 on an evening when Addison was scheduled to preach, a new pursuit that went hand-in-hand with being a Disciples educator.

Completing their studies at Carlton in 1869, Addison and Randolph were ready to make their way in the world. Addison began making plans to open yet another school; he had the full support of his father and eventually Randolph, who had accepted a teaching position in nearby Birdville, Texas, north of Fort Worth.

When Fort Worth community leaders offered the proprietorship of a school there, Joseph Clark persuaded his sons that this was their best opportunity to follow their chosen profession. In fall 1869, Addison assumed control of the school, which was at the corner of Belknap and Grove streets downtown. They rebranded it as Fort Worth Male and Female Seminary. Initially, Addison undertook all teaching responsibilities while Randolph finished out the term in Birdville.

Randolph was the more gregarious of the two elder Clark brothers and had numerous friendships with young women from the households of Clark family friends. When he met Ella Blanche Lee, he was smitten enough to consider marriage. Lee was the daughter of a prominent family and a distant relative of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee. After a two-year courtship, they married in early July 1870 in Bonham, Texas.

Ella and Randolph Clark’s wedding was a mundane affair, with Charles Carlton presiding, but the events that followed became family lore. On their trip home to Fort Worth, a man on horseback approached the wedding party’s guide to say they had traveled off the road and were now lost. The mystery savior prodded them to follow him to safety, which turned out to be an outlaw hideout. Their mysterious escort was a desperado named Touchstone.

The newlyweds’ fear subsided with the outlaws’ kindly treatment. With the roads muddy and impassable, Touchstone offered the young couple lodging for the night. In the morning, the desperadoes treated their company to breakfast before allowing them to go on their way.

The brothers, along with most Texas Disciples, were strong supporters of the early Prohibition movement, and on their campus, students were not permitted to use alcohol.

An Unwavering Antagonism to Vice

After running the school in Fort Worth for four years, Addison and Randolph saw a downturn in their fortunes when the Texas and Pacific Railroad halted expansion just outside of Dallas because of financial constraints. Fort Worth’s population plummeted in 1872 as a result of the economic downturn.

Enter Pleasant Thorp and his offer of land and a building in his budding resort town near Granbury. While legend has it that the Clarks accepted Thorp’s offer in order to get away from Fort Worth’s infamous vice district, Hell’s Half Acre, the downturn in the town’s fortunes was the deciding factor.

Addison and Randolph had families with young children, and with their prospects dimming in Fort Worth, in summer 1873 the brothers accepted Thorp’s terms. They christened their new school the AddRan Male and Female College after Addison’s first child, AddRan, who had died at 3 the previous November.

The college opened its doors that fall with a grand total of 13 students, not exactly an auspicious beginning. Because Addison had promised the students at their Fort Worth school he would finish the calendar year, Randolph handled the initial term by himself.

AddRan’s growth — 117 students, including 46 women, in its second year — can be attributed to the Clarks’ reputation as educators among Texas Disciples. Both brothers, along with their father, often traveled throughout Texas to preach at Disciples churches, where they made appeals to the families of potential students.

One of Addison and Randolph Clark’s strongest selling points to these families was their unwavering opposition to any form of vice. The brothers, along with most Texas Disciples, were strong supporters of the early Prohibition movement, and on their campus, students were not permitted to use alcohol. The Clarks also banned tobacco use on school grounds. Students were expected to follow a strict dress code that required both sexes to wear modest gray clothing and forbade women to wear jewelry.

By 1876, Randolph realized that he was behind his older brother in terms of scholarship. Randolph understood that if education were to be his life’s work, he needed to advance; he decided to step away from his duties at AddRan for two years and study at West Virginia’s Bethany College — the most prominent Disciples institution in the United States.

Addison and Randolph Clark ceded control of AddRan Male and Female College to the Texas Disciples in order to keep it from folding. Photo by Jeffrey McWhorter

Light Moments and Hard Choices

Though Addison and Randolph Clark were strong proponents of their college’s austere prohibitionist culture, they did not refrain from engaging in a bit of fun alongside the seriousness of education.

When several students plotted to dump Addison’s covered carriage into a creek, he foiled their plan by hiding in the carriage. Just as the students were about to plunge the vehicle into the water, the college founder revealed himself to the stunned group and announced that he had enjoyed the ride, but it was late and everybody should head home.

On another occasion, a few students sneaked away from study hours to hold a chicken roast in the woods. While some of the students built a fire, another climbed a tree where the chickens were roosting in order to select the meal. When the student in the tree asked the rest of the group if a particular chicken was plump enough, Addison, who was hiding nearby, answered in the affirmative. The startled student fell out of the tree and required several days of rest to recover.

Rural education had its advantages, but in 1889, the brothers faced a dilemma. The harsh financial realities of running a private school on the Texas frontier had come to a head. Tuition payments rarely covered operating costs.

And running a college remained an expensive business. The Clarks often sacrificed financially for the sake of their school. One month the school’s janitor received a higher salary than Addison, who was the school’s president.

The Clarks needed an endowment — or at least more reliable outside funding — in the worst way. Turning formal control of the school over to the Texas Disciples of Christ would provide the school with much-needed financial backing and ensure its continued existence because of the Disciples’ ability to raise contributions throughout the state.

The Texas Disciples wasted little time answering in the affirmative after receiving the Clarks’ offer, which came with the stipulation of their continued roles as instructors and officers of the school.

If the Clarks had not ceded ownership to the church, AddRan Male and Female College would likely have gone the way of most private schools in Texas during this era and folded.

Play On, Miss Bertha

In the 1890s, a doctrinal disagreement arose among Disciples regarding the use of mechanical instruments in worship services. The dispute played a significant role in a formal schism in the denomination in the early 1900s, with those opposed forming a separate denomination, the Churches of Christ.

The Clarks had no intention of entering the quarrel, but fate had other ideas. When the school held Religious Emphasis Week in February 1894, Addison granted the request of students who had asked to use a newly acquired Estey organ, an unremarkable instrument common to churches of the era, in the week’s revival services. In doing so, he unintentionally ignited a firestorm, and soon the entire community became engulfed in the controversy.

The most notable opponent to the organ’s use was family patriarch Joseph Clark.

With Addison and his father on opposing sides, Randolph attempted to ameliorate the situation by appealing for unity. But Joseph had rallied locals who supported his position and promised a walkout from a Religious Emphasis Week service if Addison allowed the organ in church. When the day arrived, congregants packed the chapel in anticipation. Bertha Mason, the student organist, sat at the Estey awaiting instruction.

When the service began, Joseph produced a petition against the organ’s use signed by 139 members of the community, which was read to the audience. In reply, Addison stated that neither he nor Randolph opposed the students’ use of the organ and that he would keep his promise.

When Mason began to play, the Clark patriarch turned to walk out, followed by his supporters. The commotion prompted a pause in the musical performance.

Addison then loudly enjoined, “Play on, Miss Bertha.”

Tensions remained high after the service. Vandals cut the rope to the school bell in protest and threw an object that broke a window light. Protesters wired the gates to the school shut.

The Clark family eventually overcame their differences on the issue, but the resulting disorder and resentment among community members played a role in the decision to move the college to Waco.

Randolph Clark often made the almost 90-mile trek to TCU’s new home, despite the increased distance from his residence in Stephenville. As the last surviving college founder, he enjoyed visiting the institution he had helped to launch.

Life After AddRan

Leaving Thorp Spring for Waco in 1896 signaled a change in direction not only for AddRan but for Addison and Randolph as well. Though the school was on the sparsely populated northern edge of Waco, it was now in an established town much larger than Thorp Spring.

The Clark brothers had always believed in the importance of a Christian education in a rural setting away from the temptations of vice that larger cities offered. Also, each brother maintained a strong sentimental attachment to Thorp Spring, the place where their children had come of age and that, after a largely transient childhood, had provided them a steadfast home.

Addison and Randolph Clark were now in a new town, working as employees at a school they had founded but no longer controlled. Policies were changing: The school’s new trustees relaxed the strict rules against alcohol, for example. The brothers began considering life beyond the institution they founded.

Addison accepted the pastorship of Central Christian Church in Waco but still taught an occasional class at AddRan, marking the end of his full-time employment with the school.

Randolph considered politics. In 1896, the Prohibitionist Party nominated him for governor; he received less than one percent of the vote.

Though Randolph Clark left AddRan Male and Female College shortly after its move to Waco, in his later years he enjoyed visiting the institution he had co-founded. Courtesy of TCU Library Special Collections

After AddRan’s first term in Waco, Randolph’s yearning for the familiarity of Thorp Spring was too much. His family had never moved from Thorp Spring, where they had extensive land holdings, and he missed Ella and the children. Meeting with Addison to discuss the matter led to the idea of a feeder school in Thorp Spring for AddRan, with Randolph as administrator and teacher. Support came from their longtime benefactor James Jones Jarvis, a Disciple who also lent his name to the project, Jarvis Institute.

But instead of enjoying a symbiotic relationship, both schools competed for donations from the same supporters. In the end, AddRan won out, and Jarvis Institute shuttered its doors in 1898.

Randolph then accepted an offer from the small community of Lancaster, Texas. The residents of the city just south of Dallas were thrilled to have someone of his stature heading a school in their community, even naming it Randolph College after him.

But as with most private, rural institutions during this period, there weren’t sufficient resources to support the school, and Randolph College closed in 1901.

That year brought the Clarks to a crossroads. Joseph Clark died in January, and neither of the brothers held full-time positions at the institution they had founded. After the closing of Randolph College in June, the younger Clark brother moved to Stephenville, south of Thorp Spring.

The next year, AddRan moved further away from its heritage in Thorp Spring when it formally changed its name to Texas Christian University in an attempt to expand its patronage.

Addison continued to serve as pastor at Central Christian Church and teach part time at AddRan until his beloved wife, Sallie’s, health began to decline. He resigned both positions — ending the Clarks’ formal affiliation with TCU — and accepted a pastorate at First Christian Church in Amarillo, Texas, with the belief the drier climate might benefit Sallie. The effort was to no avail, so the family returned to Thorp Spring in 1904.

The Clarks again started institutions of higher learning, first separately, then together with another attempt in Thorp Spring, this one named AddRan Jarvis College to capitalize on the brothers’ previous school and good name. Opening its doors in fall 1905, the school, like so many of its predecessors, was doomed by a lack of stable finances and closed four years later.

In 1908, Sallie Clark’s health declined further, and Addison again moved the family in an attempt to ameliorate her lingering illness, this time to San Diego. The move proved fruitless when Sallie died April 9 of that year. Addison returned to Texas and, after the closing of AddRan Jarvis, accepted the pastorate of a struggling church in Mineral Wells. This was his last significant position. In 1911, at age 68, he joined Sallie in the hereafter while visiting his daughter Jessie in Comanche, Texas.

Addison’s death left a void in Randolph’s life; the elder Clark had always been his mentor and trusted adviser. After serving in various pastorates throughout the state, Randolph moved back to Stephenville, where he served as pastor to Race Street Christian Church and on the John Tarleton College Board of Trustees.

In 1921, Randolph lost Ella. He soldiered on; the ensuing years saw him overcome a near-fatal snakebite, an auto accident and a broken hip.

The Clark brothers always believed in the importance of a Christian education in a rural setting away from the temptations of vice that larger cities offered Photo by Carolyn Cruz

A devastating fire destroyed most of TCU’s campus in 1910, which precipitated a move to Fort Worth. Randolph often made the almost 90-mile trek to TCU’s new home, despite the increased distance from his residence in Stephenville. As the last surviving college founder, he enjoyed visiting the institution he had helped to launch and was something of a celebrity to the students.

But time comes for us all, and in 1935 — the year of TCU’s first national championship in football —Randolph succumbed to old age at 92.

A Family Legacy

Addison and Randolph Clark were complex men, simultaneously ahead of their time and a product of their times. They were influenced by their surroundings and their ideals, which at times came into conflict. Largely progressive in their views, they nonetheless fought in the Civil War to maintain slavery. Such dichotomies are not unusual for men with big accomplishments, such as creating the first continuously coeducational institution of higher learning west of the Mississippi River.

While Addison and Randolph left their mark on higher education, their legacy is more than just the international education leader now known as TCU.

Randolph’s son Joseph Lynn Clark was co-founder of the Texas Commission on Interracial Cooperation and taught the first course in Texas on race relations while a professor at Sam Houston State Teachers College.

Another of Randolph’s sons, Randolph Lee, served as school superintendent of Wichita Falls, Texas, where he opened a night school for Black people and started a bilingual education program for the children of Latino farmworkers.

Randolph’s grandson Randolph Lee Clark Jr. became the director of the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston and is considered one of the founders of modern oncology.

Addison’s son Robert Clark earned a doctorate in history from the University of Wisconsin and taught at the University of Oregon.

Ardent Clark family supporter J.J. Jarvis and his wife, Ida Van Zandt Jarvis, were instrumental in establishing Jarvis Christian College, a historically Black college in Hawkins, Texas.

Neither Addison nor Randolph Clark ever wavered from their belief in a Christian-based education in rural Texas, so it’s appropriate that they rest in quiet places largely bypassed by modern development. Randolph is buried in Stephenville, a sleepy college town of barely more than 20,000. Addison lies 30 miles away in a cemetery at the end of Clay Street in that curve of Farm-to-Market 4 that marks the hamlet of Thorp Spring, now little more than a ghost town.

Both Clarks would undoubtedly look with pride — if not a bit of astonishment — on the major international university down the road in Fort Worth.

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related reading:

Features

The Promise of a Name

Ties to the Disciples of Christ have steered TCU from the start.

Sports: Riff Ram

Flashback to Freshman Football

Wogs players spent a year preparing to become full-fledged Frogs.

Alumni

Behind the Names

Two Burnett women have shaped TCU’s past, present and future.