Tatiana Arguello Explores Conflict in Central American Literature

The assistant professor of Spanish and Hispanic researches the lasting effects of war.

Tatiana Arguello's recent work focuses on the part language plays in causing and resolving conflict. Photo by Joyce Marshall

Tatiana Arguello Explores Conflict in Central American Literature

The assistant professor of Spanish and Hispanic researches the lasting effects of war.

A decade after a School of Americas-trained soldier killed Antonio Bernal’s wife and child in Guatemala, he plots revenge from the homeless camp where he lives as a refugee in Los Angeles.

Antonio is a character in Héctor Tobar’s The Tattooed Soldier (Delphinium Books, 1998), a novel on the syllabus of Tatiana Argüello’s Artistic Productions of the Central American Diaspora course. She wants students to read beyond the fictional characters and consider how real people of Central American heritage often bear the scars of war.

Argüello, assistant professor of Spanish and Hispanic studies, was born in Nicaragua at the end of the country’s revolution. She remembers how her family stopped rationing food after the regime of Anastasio Somoza was toppled by the socialist-minded Sandinistas in July 1979.

Tatiana Arguello, assistant professor of Spanish and Hispanic studies, examines how literature helps people understand conflict in Central America and the lingering scars of war. Photo by Joyce Marshall

The revolution and its violence became central threads in the cultural fabric of Nicaragua, where “everybody is a poet until proven otherwise,” Argüello said. Artful arrangements of words can provide abstraction for untangling issues of power, politics and the sanctity of human life, she said. Literature “can capture violence but also kind of put you far away.”

Andrew Ryder, adjunct faculty in the John V. Roach Honors College, is Argüello’s husband and research collaborator. Until they met, he “didn’t know how long there had been a tradition of philosophical and theological thought” in Nicaragua, he said. In the U.S., “there’s a lack of awareness of the richness of Central American thought and literature.”

Some people in the U.S. also are unaware of how violence changed the demographics in Central America. Guatemala, El Salvador and Nicaragua all experienced civil wars between 1960 and 1990. Three hundred thousand people, mostly civilians, died. Four million fled to the U.S., and issues revolving around integration persist.

Argüello became part of the Central American diaspora. In her 20s, she worked for Nicaragua’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. She traveled on behalf of Central America’s largest country to United Nations offices in New York City and Geneva.

The global body politic had moved on, she said, considering the struggle for control of the region settled. “In the 1990s, we were out of mind.” She came to appreciate how political facts might soften into memories, but stories move beyond rhetoric and numbers “to humanize, to show the faces.”

She spent five years in the U.S. as a doctoral student studying war stories with Central American elements. She folded those insights into a 2018 paper published in the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature.

Most of the works she explores are available in English, and many were composed in English or, as in Tobar’s The Tattooed Soldier, a hybrid sort of Spanglish. Settings range from World War I to the 21st century, when U.S.-born millennials grapple with the consequences of their Central American-born parents’ wartime travails.

Argüello said the works can help create a link between English-speaking readers and people bearing generation-spanning scars from Central American violence. Reading in Spanish can give a particular insight, she said. “I had read American poetry about violence, and it’s very precise. … In Spanish, the poetry is more fluid. It’s more connected with the senses.”

Those stories matter, Argüello said, given the ongoing influx of Central American migrants into the U.S., where many, such as Tobar’s fictional Antonio, face economic inequalities, discrimination and questions about their migratory status.

“I had read American poetry about violence, and it’s very precise. … In Spanish, the poetry is more fluid. It’s more connected with the senses.”

Tatiana Arguello

Argüello wants her students to understand the role of the U.S. with its financial and military support of political regimes in Central America. “It’s a cycle that is connected.”

The guns and machetes used by fighters in the ’70s may be relics, Argüello said, but the battles are not necessarily over. She and Ryder are studying environmental justice movements now erupting in Central America. Multinational corporations sometimes exploit the environment, causing people in the area to mobilize and fight back against the companies to defend natural settings. Some people, she said, wonder if the wars ended or simply shifted fronts.

Ryder said literature can open the window on human suffering in its myriad forms. “It’s very useful in terms of developing empathy [and] learning how other people experience the world.”

The spirit of the revolution — and the feeling of being at war — continues in Central America, Argüello said. “There’s a persistence or resilience of people. They’re still fighting, but now they’re fighting in peaceful means.”

Literature Gives Voice to Central American Conflicts

Tatiana Argüello, assistant professor of Spanish and Hispanic studies, recommends these war-related works with Central American connections:

The Unknown Soldier

Salomón de la Selva (Cultura, 1922)

Nicaraguan poet de la Selva fought for the British army in World War I. He uses poetry to give faces and voices to the soldiers who suffered silently during one of history’s most gruesome wars.

Revulsion: Thomas Bernhard in San Salvador

Horacio Castellanos Moya (New Directions, 2016)

Castellanos Moya writes about a fictional exile who returns to El Salvador after a civil war. The exile criticizes his native country in a belief that the battles never really ended. “That type of hatred is a way to really love the country,” Argüello said.

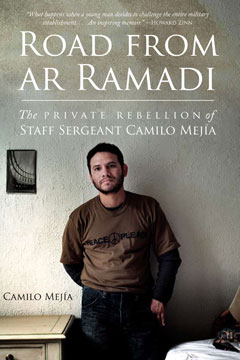

Road From ar Ramadi: The Private Rebellion of Staff Sergeant Camilo Mejía

Road From ar Ramadi: The Private Rebellion of Staff Sergeant Camilo Mejía

Camilo Mejía (The New Press, 2007)

After nearly nine years in the U.S. Army, Mejía, who was raised in Central America by Sandinista revolutionaries, made headlines in 2004 by applying for a discharge as a conscientious objector. He refused to return to his unit after fighting in Iraq and was sentenced to a year in a military prison for desertion.

The Tattooed Soldier

Héctor Tobar (Delphinium Books, 1998)

In his debut novel, veteran journalist Tobar, a son of Guatemalan immigrants, relates a refugee’s elusive quest for justice. Set in a homeless camp in Los Angeles against the backdrop of the 1992 riots, the plot reignites Guatemala’s civil war, raising the question of whether the violence ever ended or instead spilled over the U.S. border.

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related reading:

Research + Discovery

Mayan Poets, Storytellers Share their Ancient Language

A new book, translated by a TCU professor, highlights contemporary Mayan poets and storytellers.

Research + Discovery

Ancient Manuscript Describes Assimilation of Aztecs

Art historian Lori Boornazian Diel decodes the story of Spanish invasion and the struggle to find a new identity after defeat.

Features, Research + Discovery

Komla Aggor Traces Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Through Language

Descendants of African slaves use the Spanish language to understand their history in Latin America.