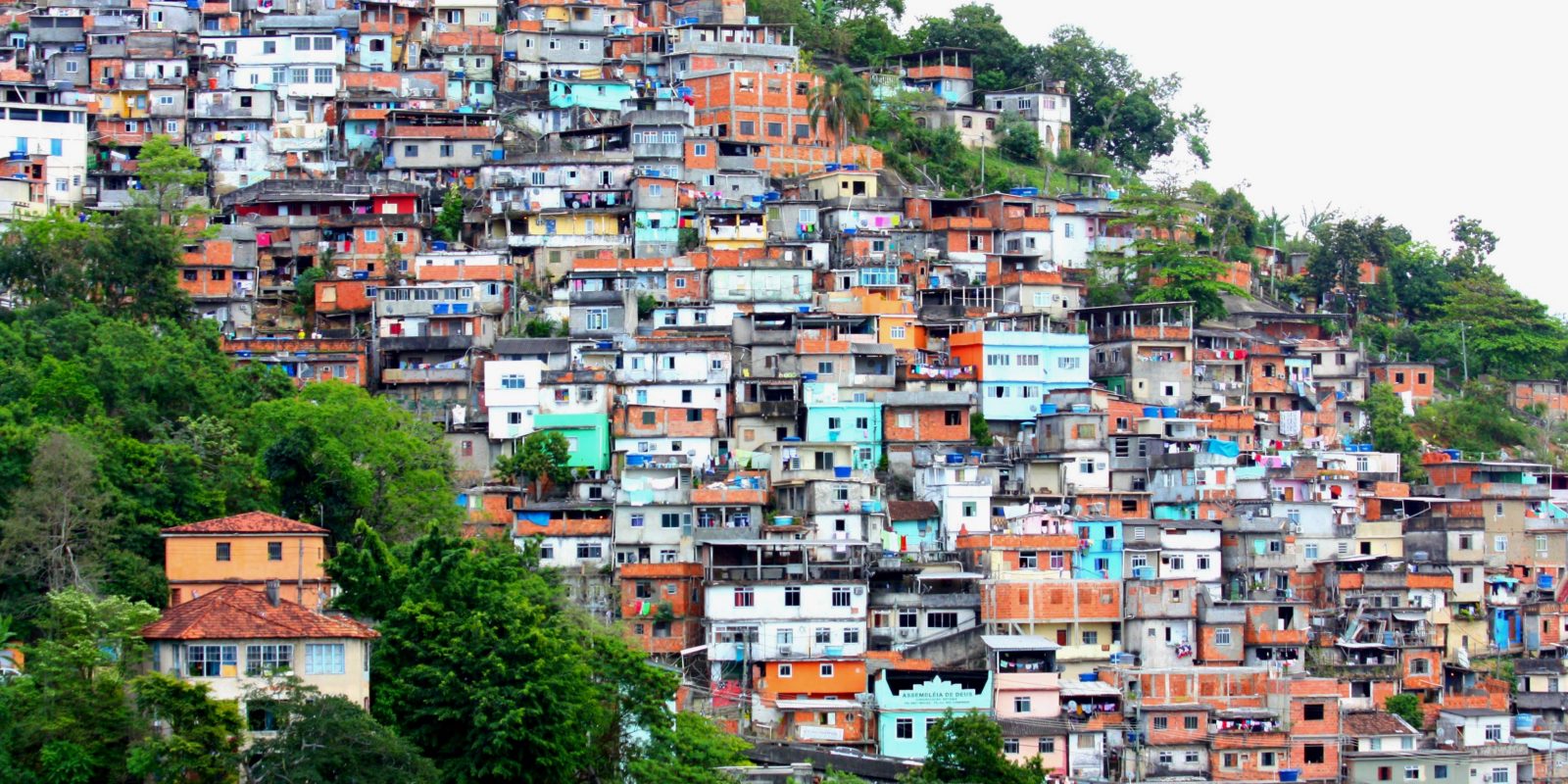

Dany13, Favéla Do Prazères, CC by 2.0

Komla Aggor Traces Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Through Language

Descendants of African slaves use the Spanish language to understand their history in Latin America.

Slavery in Latin America ended more than a century ago, but it left a mark on much more than the region’s racial and ethnic identities.

“The consequences of these things last. They last,” said Komla Aggor, professor of Spanish and Hispanic studies.

Komla Aggor, professor of Spanish and Hispanic studies, co-edited two books examining how Latin American’s Afro-Hispanic population uses literature and film to understand its cultural identity. Photo by Rodger Mallison

Africans who were ripped from their homelands and shuttled across the Atlantic to the empires of Spain and Portugal had to reimagine everything. “You couldn’t practice your own religion,” Aggor said. “Your names were changed. You couldn’t speak your language. You had to learn a new language.”

The repercussions persist in the 21st century’s Afro-Hispanic population, Aggor said. For descendants of the enslaved, “It means that, psychologically, you grew up in the dark.”

Contemporary people are still navigating ancestral identity, but now in Spanish, the language that replaced their forefathers’ native tongues. They are using literature and film to help integrate hundreds of years of divided familial and cultural identities.

Aggor is interested in how these stories are a democratizing tool to create identity. Literature, he said, can be a mutable medium for presenting multifaceted, complex characters who forge wholeness from the threads of their pasts.

Identity is the subject of two books Aggor edited with Yaw Agawu-Kakraba, professor of Spanish at Penn State Altoona: Diasporic Identities within Afro-Hispanic and African Contexts (Cambridge Scholars, 2015) and African, Lusophone, and Afro-Hispanic Cultural Dialogue (Cambridge Scholars, 2018).

“You couldn’t practice your own religion. Your names were changed. You couldn’t speak your language. You had to learn a new language.”

Komla Aggor

The idea for the books sprang from a biennial conference the professors organized in their native Ghana, the International Conference on Afro-Hispanic, Luso-Brazilian and Latin American Studies (ICALLAS), which started in 2007.

“Racial identity is definitely a hot topic,” said Steven Sloan, associate professor and chair of Spanish and Hispanic studies, who presented at the conference in 2016. He also contributed a chapter summarizing three novels about the Afro-Brazilian experience to the 2018 publication.

One of the books Sloan explored was Lucio Cardoso’s Salgueiro (Civilização Brasileira, 2007), set in a favela of Rio de Janeiro. Many inhabitants of Rio’s poverty-stricken neighborhoods, most of them descendants of Brazil’s 4 million slaves, still seek social equality, though the country outlawed slavery in 1888.

Afro-Brazilians remain relegated to the outskirts of the city, Aggor said. In the touristy parts of Rio, “If you see a black person … the likelihood is he or she works in a restaurant or something because you just don’t see them.”

While black Brazilians might wonder if they belong, their influence is heard in the country’s vernacular. The fingerprints of African languages are all over modern dialects of Spanish and Portuguese in Latin America.

Komla Aggor, professor of Spanish and Hispanic studies, specializes in 20th century Spanish literature. Photo by Rodger Mallison

“The peoples of African ancestry tend to speak in a certain way,” Aggor said. “And when they arrived in the diaspora, when they arrived in

America, they kept certain vocabulary that, amazingly, after centuries they still have.”

For instance, the names of some foods popular in Latin America originated in Africa. So did various cultural and political practices. The mixing of words happens to some extent in all languages, but Spanish in particular integrates African languages, Aggor said. The combination is “more transparent, more vivid in Spanish.”

Aggor has a theory about why: Miscegenation was encouraged in Latin America with the same vehemence that it was prohibited in the United States in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

“The rationale behind it is questionable,” said Aggor, who explained that interracial marriages were promoted in Latin American countries because officials thought the whiter and more European-seeming the population, the better. Misguided “whitening” meant that minority populations might be “absorbed to make society better,” he said.

Centuries of history, culture, language and literature come together in contemporary contexts throughout both volumes edited by Aggor and Agawu-Kakraba. The complexity of Latin America, where people of Native American, African and European ancestry still push toward integrated wholeness, has become clear throughout these works, Aggor said.

Slavery still affects the present, and these signposts are amplified through literature, Aggor said. It is very important for the larger Latin American community to understand how these events of the past came about.

The Trans-Atlantic slave trade ripped people from their African homes and deposited them throughout the Spanish and Portuguese empires. Their Afro-Latino descendants have used language to build compound identities mixing old and new cultures. But as Komla Aggor, professor of Spanish and Hispanic studies, found, identity ultimately transcends race and place.

Sources: Diasporic Identities within Afro-Hispanic and African Contexts (Cambridge Scholars, 2015) and African, Lusophone, and Afro-Hispanic Cultural Dialogue (Cambridge Scholars, 2018)

Your comments are welcome

8 Comments

Thank you, Doctor Aggor!

Thanks for bringing this to the forefront of conversation. It is a cultural topic very relevant still today that is not really addressed or even acknowledged.

Delighted to read this coverage of Dr. Komla Aggor’s work on the continuing impact of the trans- Atlantic slave trade. It is a conversation that we should be having in light of the current events in the world. Thank you.

Quite revealing. Such root-tracing studies will eventually reconnect our brothers and sisters to the motherland. Good job. Thanks.

Very insightful. It’s quite important for such hidden and unknown history to be brought to the fore for the purpose of widening our knowledge on the impact of the Trans Atlantic Slave Trade. Thank you Professor Aggor. I’ve just learnt something new.

Professor Komla Agor thank you for the insightful piece on the identity crisis of our dear Africans who were uprooted from Africa by the Spanish and Portuguese merchants in the most inhumane way to the unknown destinations all just to go and oil their commercial and industrial activities

I wonder if the Spanish and Portuguese have been able to show remorse for their actions and rehabilitate the victims of their unfair treatment?

This was a very insightful read Dr.Komla. Good work !

Nicely done, Komla! This is insightful and profound. Slavery has to be the worst sin ever perpetrated in human history. Studies like this help solve numerous mysteries about what has come of us centuries after. Great material for a documentary!

Related reading:

Research + Discovery

Identity Transcends Race and Place

Stories illuminate cultural and linguistic hybridity in the Afro-Hispanic diaspora.

Research + Discovery

Ancient Manuscript Describes Assimilation of Aztecs

Art historian Lori Boornazian Diel decodes the story of Spanish invasion and the struggle to find a new identity after defeat.

Personal Essay

The Atlantic Slave Trade Bus Tour

How a cultural tour connected the past with the present.