Industrial Sexuality: Historian Examines Egypt’s Transformation

An associate professor’s work explores how industrialization and gender roles disrupted power structures in modern Egypt.

Industrial Sexuality: Historian Examines Egypt’s Transformation

An associate professor’s work explores how industrialization and gender roles disrupted power structures in modern Egypt.

When Egyptian men moved from farms into cities in the first half of the 20th century as part of the country’s industrial transition, they had to navigate new hierarchies and redefine their masculine identities. Often, it was the women who suffered.

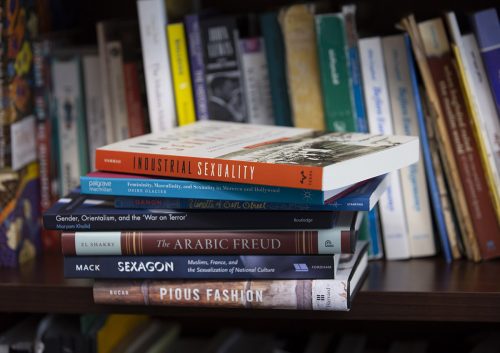

Hanan Hammad wrote a book about how industry and sexuality evolved for women during Egypt’s industrial transformation. Photo by Joyce Marshall

Hanan Hammad, associate professor of history and director of Middle East Studies, provided gender-based insight into Egypt’s labor-driven transition in her book Industrial Sexuality: Gender, Urbanization, and Social Transformation in Egypt (University of Texas Press, 2016).

Hammad said Egypt’s metamorphosis from an agrarian to an industrial economy occurred not in cosmopolitan areas such as Cairo but in midsize cities. The example used in her book is her hometown of al-Mahalla al-Kubra, the site of the Misr Spinning and Weaving Co. “The experience of the city is exceptional when it comes to this rapid transformation from craftsman to industrial,” she said. “The urbanization drive is so fast and extraordinary in a short time.”

As Misr expanded operations, agrarian men and women migrated to the city with the promise of homes, salaries and new skills. The peasant workers, or shirkawiyya, brought customs unfamiliar to the established residents, or mahallawiyya.

Culled from Hammad’s extensive research, including court and police records, memoirs, oral histories, and newspapers, the book is about these new factory workers and their interactions with the extant population. The integration was not without tensions, as the newcomers were considered primitive peasants by those already living in the city.

What Hammad calls the “social history from below” weaves together stories of adaptation and survival among the migrant lower-class workers and “provides the richly textured, ground-level account of the social dynamics of a provincial city,” said Paul Sedra, an associate professor of history at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, Canada.

Masculinity and Power

“Whether men harassed women or intervened to protect women from sexual harassment, both actions chartered notions of urban masculinity.”

Hanan Hammad

In al-Mahalla al-Kubra, men who migrated for factory jobs often lived 20 to a room and worked in a male-dominated environment, an existence far different from what they experienced at rural farms. The new life structures necessitated figuring out new ways to show masculinity.

“They needed to defend their manhood and pride against each other and supervisors,” Hammad said. “Men would identify their masculinity around harassing women.”

At work, female laborers were often sexualized and harassed by male colleagues. Sexual harassment was a way to protect and show off masculinity but also part of a conflicted “good masculine” identity. “Different groups have different understanding of what it means to be the ‘good masculine,’ ” Hammad said. “Whether men harassed women or intervened to protect women from sexual harassment, both actions chartered notions of urban masculinity.”

But women were adapting to new lives as well. As al-Mahalla al-Kubra grew, sex workers and land ladies — the women who bought land to house the workers and were considered caretakers — also moved to the city. “They had power over men. Men who worked during the day shift had interactions with those women, especially those with husbands who were working. They played a huge role in helping men adapt to urban life,” Hammad said.

Violent Discipline

The harassment, as Hammad discovered, also occurred between men. Those promoted to management positions sometimes used violence as a tool to force obedience. “Violent discipline was common. It was a way to make sure work is done,” she said. “They need to defend their manhood and pride against each other and supervisors. When you slap workers, you are creating this lawless situation or sense of anarchy.”

Hanan Hammad, associate professor of history and director of Middle East Studies, collected tales of Egypt’s industrial transformation from al-Mahalla al-Kubra, her hometown. Photo by Joyce Marshall

A changing political landscape influenced in part by the lingering effects of British colonialism, which ended in 1954, forced the national government to crack down on workers’ violent behaviors. Afandiyya, or educated men, sometimes collaborated with law enforcement and political leaders to promote a skilled, civilized form of masculinity — and support British-friendly politicians.

Sometimes these citizen-leaders were created by the state to discourage rebellion among unskilled workers. In the workplace, these malcontents may have complied in terms of actions, dress and manners, but they were still subversive, engaging in sabotage of company profit and labor strikes. They were fighting back against the capitalist class of factory owners as much as they were fighting against the British colonizers.

“Part of spreading their civilization included stopping prostitution and homosexuality. This puritanical thinking coming from Europe spilled over,” Hammad said. The core reason, she said, was economics. “The good citizen is the productive citizen.”

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related reading:

Features

Professors Track China-Russia Alliance

A new research initiative illuminates six decades of Sino-Soviet relations to help predict future patterns.

Features, Research + Discovery

China and Russia’s Relationship: A Q&A and Timeline

Carrie Liu Currier and Kiril Tochkov discuss trust, differences and rivalry between the two superpowers.

Campus News: Alma Matters

What date (or event) most changed the course of history?

Eight faculty members answer the question.