Ancient Manuscript Describes Assimilation of Aztecs

Art historian Lori Boornazian Diel decodes the story of Spanish invasion and the struggle to find a new identity after defeat.

Ancient Manuscript Describes Assimilation of Aztecs

Art historian Lori Boornazian Diel decodes the story of Spanish invasion and the struggle to find a new identity after defeat.

In late 2016, Lori Boornazian Diel cracked a passage of mystifying hieroglyphics in an old pictorial manuscript known as the Codex Mexicanus. The breakthrough proved a watershed moment for the art historian, who began studying codices in graduate school as part of an interdisciplinary curriculum focused on pre-Columbian culture and art.

Art historian Lori Boornazian Diel is contributing new understanding of how Aztecs perceived the loss of an empire. Photo by Robert W. Hart

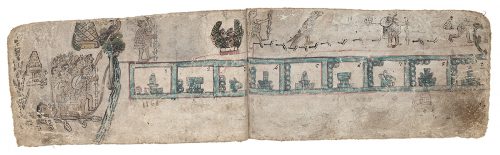

Written in Nahuatl, a native language, the Codex Mexicanus offers rare insights into how the Aztecs struggled to assimilate following the Spanish conquest in 1521. Like other Aztec pictorial manuscripts created after conquistador Hernán Cortés’ decisive victory, the Codex Mexicanus was small enough to carry in a pocket and probably was intended for daily use.

Written at the end of the 16th century on paper made from the fibers of a ficus plant, the 100-page book measures only about 4 inches by 8 inches. “The Codex Mexicanus had actually been dismissed because it wasn’t that pretty,” said Diel, professor of art history at TCU. “There are other codices that are much more beautifully painted, more like the European illuminated manuscripts.”

In all likelihood, generations of scholars also ignored the Codex Mexicanus because they didn’t understand much of the work’s meaning and implications. “No one had bothered with it since the early 1950s,” Diel said, “which was something that drew me to it.” She also thinks the fact that the fragile book has long resided in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, the national library based in Paris, contributed to its relative obscurity

“It’s in poor condition, with the paint flaking off when you turn pages,” said Diel, who arranged to see the document on two occasions. The first time was in 2012 with a grant from the TCU Research and Creative Activities Fund.

With a second TCU grant, she returned to Paris in 2016 to conduct research for a book about the manuscript. Diel also has received support from the Robert and Mary Jane Sunkel Art History Endowment. The University of Texas Press will publish Diel’s book, The Codex Mexicanus: A Guide to Life in Late Sixteenth-Century New Spain, in December 2018.

“The Codex Mexicanus has long been treated as a miscellany and has thus defied an explanation that accounts for the whole,” said Elizabeth Hill Boone, chair of the History of Art, Design, and Visual Culture Department at Tulane University and Diel’s longtime mentor. “What Lori has been able to do is reveal how important this document is to understanding the yearnings of the indigenous elites along with how they adopted and adjusted European literary genres. This opens a window, bringing the reader deeper into the world of the Nahuatl intellectuals in the late 16th century.”

Cultural Collision

In many ways, the Codex Mexicanus documents the cultural collision between the conquering Europeans and a native population that had dominated its region for centuries.

“Egypt and Greece seem to get all the attention, but ancient Mesoamerican cultures, including the Maya, the Inca and their predecessors, are fascinating,” Diel said.

Even as an undergraduate student at Emory University, she was drawn to the conquest era’s literature and artwork, particularly images depicting early contact between Aztecs and Spaniards.

“When the Spaniards arrived, they burned the books they thought were pagan, so there are few pre-Conquest Aztec books that have survived.” Diel has largely identified the circuitous path the Codex Mexicanus took on its journey to France. “It’s ironic that the Aztec books that did survive mostly survived because they happened to be sent back to Europe as curiosities.”

The Codex Mexicanus is a small 16th-century book written in Nahuatl, a native Aztec language. Courtesy of Lori Boornazian Diel

Candace Carlisle Vilas ’15 (MA ’17), who assisted Diel with research for the book and currently works at the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, said, “Smaller texts like the Codex Mexicanus produce a history seen through the eyes of the people about their home and heritage before the Spanish invasion. We don’t have a lot of manuscripts before the conquest, which makes the Spanish Colonial ones that much more important.”

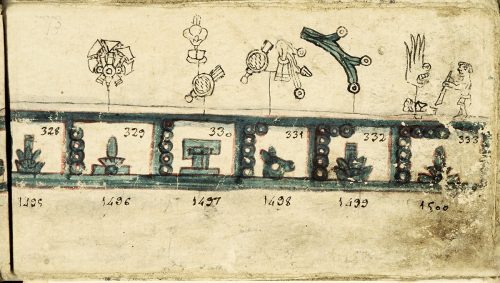

To that end, Diel’s study of the Codex Mexicanus illuminates how the Aztecs viewed themselves and their place in the world before and after their crushing defeat at the hands of Cortés. Written by that society’s educated elites living in what would become Mexico City, the codex traces more than four centuries of Aztec history starting in A.D. 1168.

“A lot of people think with the conquest, the Aztecs just die out,” Diel said. “Instead, they begin negotiating what their new status is. Here they had been leaders of this vast empire, when the Spaniards come in and impose a new empire on them. In some ways they hold onto their old traditions, but in other ways they embrace Spanish culture and Christianity.”

Aztec Almanac

The Codex Mexicanus offers a window into this new reality, one that had undergone a seismic political, religious and cultural shift. Filled with a mixture of Aztec hieroglyphics and art, the manuscript can be seen as an almanac, delving into a range of topics that would have influenced and shaped everyday life for the upper social echelon of colonial-era Mexico.

Certain parts of the book translate words and pictures into Spanish. Other sections include depictions of the Christian and Aztec calendars with an emphasis on signs of the zodiac. The inclusion of medical astrology, which was widely popular in Europe at the time, alongside genealogies and local histories help make the Codex Mexicanus challenging to categorize.

“You need to remember that at the end of the 16th century, 80 percent of the indigenous people have died, and they don’t really understand that the Spaniards brought the diseases that decimated their population,” Boone said. “This is an age of great trauma, and the Codex Mexicanus takes a European encyclopedic form as a guide for living.”

For those contemporary readers seeking spiritual guidance, the codex also served as a resource for religious beliefs and practices.

“Things get messy in this living document where people were adding to it,” Diel said. “And honestly, it confused me for the longest time. In one section in particular, I could not figure out why they were putting Christian symbols including a crucifix up at the top of a certain page.”

Symbolic Discovery

Diel devoted part of a Harvard University-administered fellowship at Dumbarton Oaks, a research library in Washington, D.C., to solving the mystery. At one point during the fall of 2016, Boone, a past director of pre-Columbian studies at the venerable research library and collection, shared an advance copy of her book on pictorial catechisms with Diel.

The Codex Mexicanus illuminates how the Aztecs viewed themselves and their place in the world before and after their crushing defeat at the hands of Cortés. Courtesy of Lori Boornazian Diel

“Then it clicked,” Diel said. “I realized I was looking at a translation into the Aztec language of the Articles of Faith. They used signs to spell out the words like a hieroglyphic text.”

Indeed, of the 14 small discs or circles drawn at the top of the page, Diel identified seven as pertaining to God and seven to Jesus Christ as man.

“It was a wonderful discovery,” Boone said. “Not only did it flesh out her project, but it gives us an example of a pictographic catechism that is very early. Lori is an extraordinary scholar who has good vision and great insights, but she’s also extremely careful with her work.”

Diel also sees the manuscript as an important tool for contrasting the artistic styles of the Old and New Worlds: “The moment the Codex Mexicanus was being created, Europe is going through the Renaissance and their style of art is so illusionistic, whereas the Aztec style is very flat and more simplified.”

Also interesting is a sense of spin Diel inferred from the work. In that, she focused on what was missing from the manuscript. “The Aztec are striving to suppress their violent reputation,” she said. “In the codex, you see them recording how they conquer this city and that city, but they rarely show the [human] sacrifices that go along with that. There is one image where they are victims of the sacrifice, but they never show themselves as sacrificing other people.”

“I realized I was looking at a translation into the Aztec language of the Articles of Faith. They used signs to spell out the words like a hieroglyphic text.”

Lori Boornazian Diel

Such a notable absence bolstered Diel’s conclusions that the authors used the manuscript, in effect, “to say they have an Aztec foundation but are becoming a Christian nation just like Spain. In a way they are equating themselves with Rome as the Christian capital of the Old World. And they are definitely giving themselves a prestigious history that doesn’t include sacrifice.”

Concurrent with the writing of the Codex Mexicanus, many Spaniards arriving on Mexico’s shores became fascinated with the Aztecs and their history. “There were debates going on in Spain during the 16th century that if the Aztecs are not rational, then they can be enslaved,” Diel said. “But if they are rational, they can be taught Christianity and be free.”

Diel said most of the friars and other Europeans who interacted with the indigenous population in Mexico reported back how rational and civilized they were. “One way of thinking about these two civilizations coming together would be like if aliens were to land on our planet today,” she said. “But there’s also that basic humanity, and the Aztecs and the Spaniards manage to communicate and build this new world together.

“At its core, the Codex Mexicanus gives us a glimpse into the coming together of these two very different traditions.”

Your comments are welcome

1 Comment

A very eurocentric view of the transformation of assimilation, in order to avoid further genocide. Assimilation kills the culture in order to survive in a European standard. Killing, waging war, taking land is justified because they are saved by newfound religion. How wiping out 95% of some 6 million people was right or better than, them sacrificing up to a thousand a year due to low harvest seasons. “Por favor compa, no me defiendes.” They had fully operating cities, running water, schools, health care and even a government. But yes, thank the lord for saving us from our savage ways (by wiping us out and striping us our culture)

Related reading:

Campus News: Alma Matters

Learning in the Art Museum

Students experience art education beyond the classroom in local museums.

Features

Curator Brings Discovery to Smithsonian as NASA Considers Mars

Space historian Valerie Neal shares stories from shuttle era.

Research + Discovery

Using Art to Treat Illness and Trauma

Amanda Allison and her students at TCU earned acclaim for designing therapeutic art programs.