Robert W. Hensley | Moment | Getty Images

Unlocking Palo Duro’s Mysteries

Geologic detective work unearths clues to evolutionary history in the prehistoric rock.

EVERY YEAR, JOHN HOLBROOK, professor of geology, gives graduate students in his Sequence Stratigraphy class a list of potential research projects. The studies have taken students from the Grand Canyon to the Dead Sea. But one location has drawn special interest in recent years: the Palo Duro Canyon.

Located in the Texas Panhandle, Palo Duro — 120 miles long, 20 miles wide and 880 feet deep — is the second-largest canyon in the United States. The gash in the earth was carved out of the surrounding shortgrass prairie by the Red River over millions of years. The river water has exposed layers of rock dating back hundreds of millions of years.

“The rocks of the Palo Duro Canyon are not just beautiful,” Holbrook said, “they also tell a story.”

Inside the rock lie answers to questions about what that area looked like several hundred million years ago and what was roaming that patch of earth.

A giant repository of vertebrate fossils lies in Palo Duro’s sedimentary layers. The fossils have drawn paleontologists from around the world who seek a deeper understanding of the evolutionary history that shaped the modern- day animal kingdom.

“The fossils in the rocks have gotten a lot of attention,” Holbrook said. “But where the rocks and the fossils came from and how they got there hasn’t.”

Holbrook’s students have been working to fill that knowledge gap.

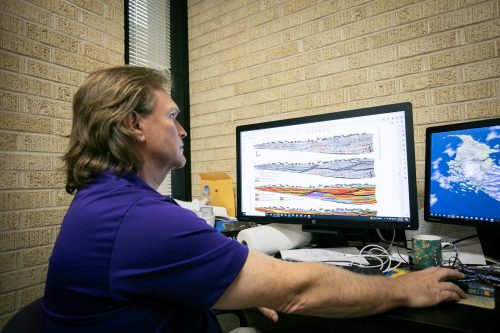

John Holbrook uses a microscope in his lab at TCU to look at sediment from the Palo Duro Canyon, where he has led students in field work. Photo by Rodger Mallison, September 27, 2023.

TRIASSIC STORMS

In spring 2021, Grayson Lamb was the first of Holbrook’s graduate students to visit Palo Duro. His objective was to examine its unique and unexplained sedimentary outcroppings dating back to the late Triassic Period, roughly 212 million years ago. An outcropping, in geological terms, is exposed ancient bedrock revealed on Earth’s surface.

“The main interpretation at the time was that the Palo Duro used to have a flood plain or a river channel,” Lamb said. “But these massive outcrops of sediment told a more convoluted story.”

The sedimentary outcroppings in the Palo Duro were formed by rivers and flood plains. Lamb believed these were not typical constant- flow rivers, but rather extremely high-energy water flows.

He collected data to understand the region’s prehistoric rain and flood patterns. He concluded that the canyon was a semi-arid flatland 212 million years ago and that it was regularly bombarded by mega-monsoons.

“Picture a place pretty much like West Texas today,” Holbrook said. “But now picture every once in a while, a massive storm comes and turns the whole place into a flooded torrent. That would have been the Palo Duro Canyon during the Triassic Period.”

The heavy rain would create high-energy water channels that would run through the usually stagnant land.

“These episodic floods were extremely violent and created these high-energy rivers that would be around for a couple of days and then be gone again,” Holbrook said.

After the floods receded, mud and silt would settle out of the waning river into the features cut out by the storm. This process of flooding and filling repeated with every monsoon over millions of years, depositing more and more sediment into these concentrated regions until they formed the outcroppings.

“Picture a place pretty much like West Texas today. But now picture every once in a while, a massive storm comes and turns the whole place into a flooded torrent. That would have been the Palo Duro Canyon during the Triassic Period.”

John Holbrook

ANCIENT GRAVES

Samuel Walker, another graduate student, expanded the research the following year. In an April 2023 paper co-authored by Holbrook and published by the International Association of Sedimentologists, Walker took samples and measurements of the canyon’s outcroppings to tell a more complete story of what happened at Palo Duro.

“Our paper really focused on the unique stratigraphic architecture,” Walker said. “We identified sedimentary structures that are generally few and far between and generally misinterpreted or unrecognized in the rock record.”

These sedimentary structures included the outcroppings that were the focus of Lamb’s studies. Walker’s work helped solidify the mega-monsoon theory and disprove previously accepted misconceptions about how the canyon formed.

John Holbrook has seen student start to uncover what the region around Palo Duro Canyon looks like and what inhabited it as far back as 200 million years ago. Photo by Rodger Mallison

This mega-monsoon theory also explains the concentration of fossils found in the outcroppings. Creatures living in the Palo Duro Canyon during the late Triassic Period would drown in the sudden floods. When the temporary rivers dried back up, the bodies at the bottom would be buried under the sediment that refilled those riverbeds. Those remains would be preserved for more than 200 million years as more sediment piled on top after every heavy rain.

ZIRCON DATING

In 2023, graduate student Blake Bezucha returned to Palo Duro to study how far the ancient seasonal river flows extended.

Using zircon crystals extracted from volcanic rock dating back to the Triassic, Bezucha is adding to the chronology of the canyon’s geological history through unique lab analysis.

“Zircon dating is the most descriptive tool we can use today to decipher ages of rocks that scale on the hundreds of millions of years of age,” he said.

The process is incredibly accurate because the lead inside zircon crystals was exclusively produced through the radioactive decay of uranium, which is also inside the zircon crystal. Researchers use zircon’s ratio of uranium to lead to measure age.

After testing zircon samples from the Palo Duro Canyon and New Mexico, Bezucha found evidence that these Triassic-era seasonal rivers — along with the mega-monsoonal climate that shaped them — extended well into inner Pangea in modern-day Palo Duro Canyon and West Texas, he said. “The work I did uncovered and added thought to the theory that there was an ancient river system that existed in the Triassic from southeast Texas to present-day Nevada.”

A more specific measurement of the canyon’s geologic age also provides paleontologists with critical insight about the point in time in which the fossils originated.

“What’s particularly impressive is that the age of these rocks is somewhere around 212 million years old,” Holbrook said. “Because that is the one point in time in that one little patch of the late Triassic Period where dinosaurs and mammals and birds and therapsids are all living on Earth at the same time.”

Paleontologists are flocking to the Palo Duro because the late Triassic Period is a turning point in the evolutionary development of countless species. The canyon, with its repository of fossils from this period, will help paleontologists understand how these creatures have evolved and thus how they may change in the future.

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related reading:

Life on the Fringe

Tricia Jenkins’ podcast on growing up in a cult draws acclaim.

Paging Through History

A project to catalog a Jewish collection at the TCU library uncovers a mystery in a medieval manuscript.

Immersed in Exercise

Kinesiologist Robyn Trocchio turns to virtual reality to help people have fun getting fit.