Paging Through History

A project to catalog a Jewish collection at the TCU library uncovers a mystery in a medieval manuscript.

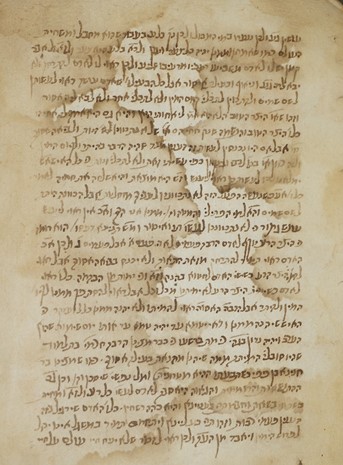

Julie Christenson found mysterious pages recycled into a medieval manuscript; Ariel Feldman discovered their origins. The text is part of the TCU library’s special collection of books on Jewish faith and culture. Photo by Rodger Mallison

Paging Through History

A project to catalog a Jewish collection at the TCU library uncovers a mystery in a medieval manuscript.

THE PAGES OF A HANDWRITTEN HEBREW MANUSCRIPT discovered in the Mary Couts Burnett Library have changed countless hands during the last 400 years: the author who wrote them, the contemporaries who read them, the bookbinder who tore them apart and used them as scrap paper, the collector who brought them across the ocean, the librarian who discovered them and the professor who unlocked their history and meaning.

In 2020, a rare-books librarian at TCU discovered the pages pasted inside a small volume containing two medieval books on Jewish spirituality. She emailed photos of those pages to Ariel Feldman, the Rosalyn and Manny Rosenthal Professor of Jewish Studies at Brite Divinity School.

The librarian, Julie Christenson, recognized that these endpapers, which attach a book to its front and back covers, were recycled; small holes on the edges showed that the endpapers had come from another bound book.

“Binders would use scraps to kind of reinforce the binding. And so they would tear up old books,” Christenson said. “But now we often value that waste more than the printed book.”

Feldman was excited by the discovery; he follows “Books Within Books: Hebrew Fragments in European Libraries,” an online project in which scholars document such finds. His wife, Faina Feldman, a technology expert who is fluent in Hebrew, also was intrigued.

“We blew up the images,” Ariel Feldman said, noting that the text, much of it abbreviated, was difficult to read. His ongoing scholarship on the Dead Sea Scrolls places his expertise in a much earlier era.

As the couple began deciphering the text, they unlocked a single sentence. It read, “I am going to die.”

JOURNEY TO TCU

The volume came from the collection of Israel Otto Lehman, who had worked as rare-books curator at Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati. Lehman had traveled through the Middle East, amassing a personal collection of books about Jewish faith and culture.

In 2002, TCU purchased Lehman’s library of more than 100 books.

Stylized script, water damage and the use of abbreviations made deciphering the mysterious Hebrew endpapers a difficult task. Courtesy of Ariel Feldman

When Christenson arrived at TCU 15 years later, she found that the collection hadn’t been cataloged.

As she began leafing through the volumes — some still packed in cardboard boxes or plywood crates — she recognized several rare books. Christenson invited professors to bring their classes in to examine the items as she cataloged them.

“Julie has spent long hours making our Judaica collection visible and turning it into a great tool for teaching,” Feldman said.

Once the Feldmans cracked that first ominous phrase, their work picked up speed. Originally, they suspected that the endpapers might have been from somebody’s last will and testament. As they continued reading, they found biblical names and quotations.

Feldman compared the text to a preacher giving a sermon and ascribing meaning to a biblical phrase, only to then offer second, third and fourth possible meanings for the same words. He noted the writing’s strong mystical stream of thought, called Kabbalah.

“One striking feature was kind of the prevalence here in this text of the idea of an immortal soul that … transmigrates, or what we call reincarnation,” Feldman said. He knew the idea existed in Judaism but didn’t know how central the belief had been for medieval Jews and Kabbalists.

“It’s actually a very powerful view of being. It gives explanation to so many things: ‘I suffer in this life because I’ve done something in the previous life, and God gives me a chance to amend, change, maybe become better.’ ”

Once the Feldmans translated the pages, he entered the text into Google to try to determine the origin of the words.

“We couldn’t find a match,” he said, “but we did find a partial one.”

The book was Ba‘ale Berit Avram (The Allies of Abram), a 400-year-old commentary on the Bible by Jewish mystic Abraham Azulai. The original manuscript is held by the Jewish Theological Seminary library in New York. Feldman found that while the well-known Kabbalist’s book had much in common with the endpapers’ text, it wasn’t the same.

A note in the margin of Azulai’s book revealed that while writing his 700-page manuscript he had used a commentary on Bible verses written by anonymous “men of old.” That margin note, Feldman said, was the missing piece of the puzzle.

“What Azulai copied from that source fit my text like a glove,” Feldman wrote in an account of his research. “Now I finally knew what was in those handwritten pages glued into the covers of the book from the TCU library. It was the long-lost source that Rabbi Azulai had in Gaza in 1619 and that has now miraculously re-emerged in Fort Worth.”

“Besides the TCU library,” Feldman said, “there is not any other place in the world we know of that source existing.”

SHARING THE RESEARCH

In March 2023, Christenson organized an exhibition, “Uncovering TCU’s Hidden Treasures: Rare Bibles of the TCU Library,” spotlighting volumes from Lehman’s collection. Feldman joined Christenson for the exhibition’s opening, where each spoke about the collection’s significance.

Julie Christenson arrived at TCU in 2017 and discovered a collection of books purchased 15 years earlier that hadn’t been catalogued. She stumbled upon a medieval find. Photo by Rodger Mallison

The Feldmans published “New Binding Waste Fragments: A Source of R. Abraham Azulai’s Ba‘ale Berit Avram?” in the 2022 edition of Materia Giudaica, an Italian journal of Judaica studies.

The article includes the full Hebrew text from the endpapers; it also documents parallels with Azulai’s The Allies of Abram, making the case that Azulai quoted from the pages found at TCU.

In September, Feldman traveled to St. Edward’s University in Austin, Texas, where he shared the research as part of his lecture on Jewish-Christian dialogue.

The research also inspired a new class, From Enoch to Kabbalah: Introduction to Jewish Mysticism. Feldman’s offering debuted in fall 2023 at Brite and is also open to TCU undergraduates. As with his other classes, this course includes a visit to special collections to examine rare Jewish texts.

“I’m not a mystically inclined person, but I have to say that when I read this text … I do find quite a bit of nourishment for spiritual quests or interests that I have always had,” Feldman said. “It’s very interesting to see what others have been thinking and how they understood scripture and how it was making them think about deeper questions of good and evil, sin and righteousness.”

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related reading:

Life on the Fringe

Tricia Jenkins’ podcast on growing up in a cult draws acclaim.

Immersed in Exercise

Kinesiologist Robyn Trocchio turns to virtual reality to help people have fun getting fit.

Deeper Compassion

Joe Hoyle’s capstone project examines the impact of empathy training on scuba volunteers.