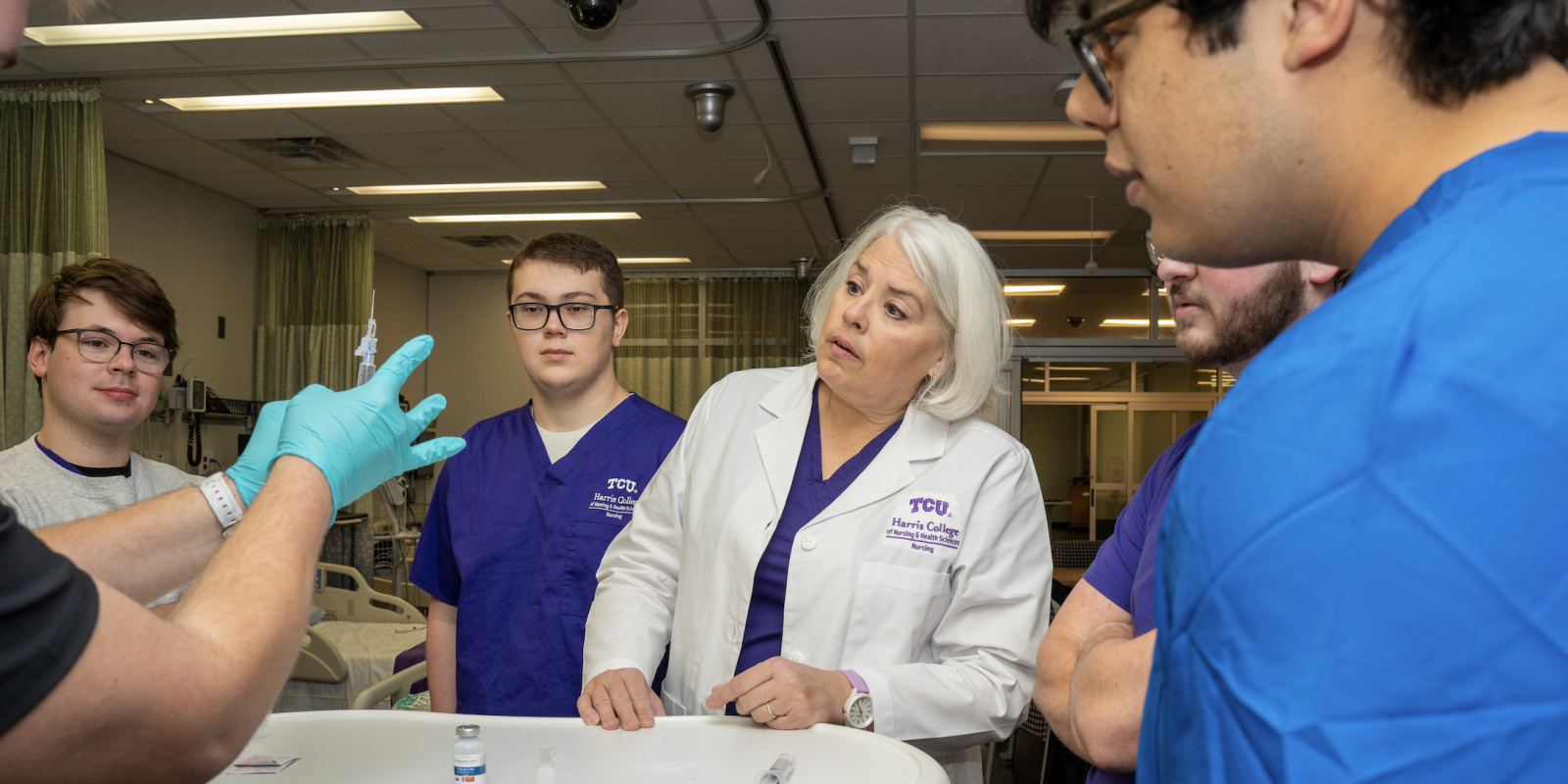

Maura Lindenfeld wants men to feel a sense of belongingness in TCU’s nursing program.

Maura Lindenfeld’s research reveals barriers for male nursing students

The U.S. health care system needs more men in nursing. In 2022, only 11.2 percent of nurses were men, reports the American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Hints of this underrepresentation can be found in our language. “Woman doctor” is no longer in parlance, but “male nurse” still pops up, said Maura Lindenfeld, assistant professor of nursing and an urgent care pediatric nurse practitioner at Cook Children’s Medical Center. “And men will say, ‘I just want to be a nurse.’ ”

Lindenfeld’s research examines the sense of belongingness men feel in nursing education programs, how this experience affects academic success and whether a strong sense of belongingness may affect the intent to complete a nursing education program.

The belongingness hypothesis, first described in a 1995 Psychological Bulletin study, centers on a person’s need to form and maintain a social network of robust, stable relationships and to feel secure as a member of a group. A person may experience poorer health and well-being without a sense of belongingness.

When Lindenfeld first dug into the topic, “I quickly realized that [men] are a horribly underrepresented population in nursing,” she said. In her nursing career, she has worked with only about a half dozen men in nursing.

While the American Association of Colleges of Nursing calls for nursing programs to recruit students with varied backgrounds, progress is limited, Lindenfeld said. “We’re making some headway … but not in terms of gender.”

Between 2018 and 2022, nursing baccalaureate students from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups increased from 33.6 percent to 43 percent. However, the proportion of men in undergraduate nursing programs stayed static — 12.9 percent in 2018 and 12.8 percent in 2022.

Past research suggests that for any student, not feeling a sense of belongingness can translate to poorer academic performance and potentially to higher attrition rates. Lindenfeld said that to recruit men to study nursing — and to keep them in school — addressing that lack of belongingness would be a good place to start.

Tom Strandwitz performs a stethoscope diagnostic on fellow nursing senior Lucas Turner.

Asking for Help

Lindenfeld worked with the National Student Nursing Association to survey 252 nursing students who identified as men and published the results in her 2022 dissertation and in two 2024 articles published in Nurse Education in Practice and Teaching and Learning in Nursing.

She used a measurement tool that divides belongingness into three essential components — esteem, connectedness and self-efficacy. Esteem is feeling valued and respected by others, and connectedness is feeling accepted by others. Self-efficacy is believing in one’s ability to succeed — and her research found that it was the biggest predictor of success.

Self-efficacy often requires a willingness to ask for help. Before Tristen Bohlman ’24 enrolled at TCU, he was a U.S. Army ambulance medic. He recounted how, after not having used an oxygen tank in a while, he forgot how to turn it on. “After struggling for about 20 to 30 seconds, I finally was just like, I gotta ask for help — like it’s either keep struggling with this [and] this person doesn’t get oxygen or ask for help.”

Maura Lindenfeld says nursing education programs need to help men feel like they belong. Doing so will assist in recruiting more men to study nursing and begin to close the profession’s gender gap.

The experience was a valuable reminder, he said, of the necessity of being inquisitive and engaged, a mindset that served him well in TCU’s nursing program.

Lindenfeld recommended that nursing programs institute interventions and ongoing practices that would help build an efficacy reservoir to empower students to ask for and receive the resources they need to succeed. These interventions could include establishing support groups and formal mentorships or enhancing the curriculum and learning environment to encourage students to seek assistance.

She said that teaching self-efficacy as a cultural backbone of a nursing program would result in “instilling that confidence that [students] can meet all of the milestones needed to graduate.”

Concerning a student’s confidence in success, bias in the classroom and in clinical settings can do real damage. Men’s experiences on some clinical rotations can differ greatly from women’s, Lindenfeld said. “Particularly in the obstetric rotations, they are asked by either the laboring woman themselves or by other staff to leave the room.”

Nursing education programs may also be structured differently for men. On a maternity clinical rotation, Bohlman and his male peers saw three cesarean sections and zero vaginal deliveries, whereas female classmates saw mostly vaginal deliveries. “That unit definitely divided us up so that we wouldn’t see certain things,” he said. “It felt like it was a predisposition almost from the beginning.”

Along with potentially damaging students’ sense of belongingness, these experiences can lead to men not getting as much obstetrics experience as their female counterparts, which ultimately can translate to fewer men in the field of obstetric nursing.

Another common bias plays out when men are the default go-to person when patients need to be moved. “You’re a man,” Lindenfeld said. The logic goes, “Therefore, you’re strong. Therefore, you’re going to do all the heavy lifting for us because we are women, and we are not strong.” She pointed out that proper body mechanics, teamwork and assistive devices make physical strength a moot point.

To foster a feeling of inclusion, exams and textbooks should also include a variety of pronouns when referring to nurses, Lindenfeld said. Faculty should be trained on helpful and unhelpful ways to interact with male nursing students.

Role Models Matter

Past research has identified that men in nursing programs frequently experience role strain, or feeling compelled to defend their masculinity or career choices. Men report that people make assumptions about their sexuality or lob accusations that they’re in nursing only because they couldn’t get into medical school and thus are not very intelligent.

Dillion McPeak ’24 said he has experienced the latter assumption, as well as the implication that men are less dedicated students, which he dismisses. “We’re as invested in our education as everyone else is.”

Each of these microaggressions on their own may not sound so bad, Lindenfeld said. “But when you get it constantly, over and over and over again, it becomes exhausting.” It can erode a student’s sense of belongingness and diminish the intention to complete schooling.

She encourages students to join support groups and invest in close relationships with peers to increase a sense of connection that might lead to success.

McPeak said that friendships helped him through to graduation. “My nursing guys, we are a tight group, and we will go out and watch the football games on the weekends, and then the next day, we’re staying late after class to study for the exam.”

“We’re as invested in our education as everyone else is.”

Dillion McPeak

A good support system for men doesn’t have to be made up of only men, he added. “I found it easier to gravitate toward the men in my program personally. But that’s not everyone’s story.”

Mentorships are especially vital, Lindenfeld said. “What we know is that if you have a role model or a mentor who looks like you, you do better.”

McPeak said he found a valuable mentor, “the coolest critical care emergency room nurse, and he’s absolutely bad to the bone, and he can joke around just like me and all my friends.”

Mentors help students succeed, and one day those students can become role models themselves. Lindenfeld calls this process the “cycle of improvement.” Boosting the number of men graduating from nursing school also ultimately increases the number who are teaching in academic or clinical education and providing mentorship to the next generations of nurses.

The implications of Lindenfeld’s research could extend beyond helping students succeed. Informed recruitment and retention of an array of students could increase the number of nurses overall, she said. “We have a shortage, [and] not just a national shortage — there’s actually a global shortage of nurses.”

Your comments are welcome

1 Comment

If you have male nursing students who want a male (I am a retired RN), I would be happy to help.

Related reading:

Research + Discovery

Prescriptions for Chronic Inequities

TCU researchers seek to close gaps in health care access and outcomes for underserved people.

Features

Pioneers in Purple Scrubs

TCU’s first nursing students of color have made their mark in health care and opened doors for others to follow.

Alumni

Allene Jones, 1933-2015

Remembering a trailblazer

Allene Jones ’63, among first black students at TCU and first black professor, passes away after rich career in nursing and teaching.