Bob Schieffer earned many awards during his legendary career in newspapers and television, but the longtime journalist says he gets the most satisfaction from seeing the people he mentored succeed.

A Storied Life

The ever-evolving Bob Schieffer reflects on the state of journalism and his first solo art exhibition.

Veteran journalist Bob Schieffer ’59 covered the assassination of JFK, the Vietnam War, Watergate and the 9/11 attacks. He anchored the CBS Evening News for 23 years. As chief Washington correspondent, he reported on the Pentagon, the White House, Congress and the State Department. He moderated three presidential debates. And he led Face the Nation, one of the country’s longest running TV news programs, from 1991 to 2015.

Schieffer, an eight-time Emmy Award winner, doesn’t think about individual accomplishments when he contemplates his legacy. “The thing that I get the greatest satisfaction out of right now, at this time in my life, is watching these kids who worked for me,” he said. “I’m just so proud of them.”

Among the Schieffer protégés is Kaylee Hartung, who served as his assistant on Face the Nation from 2007 to 2012. She is now a contributing correspondent for NBC News’ Today show and a sideline reporter for Amazon Prime Video’s Thursday Night Football NFL broadcast.

“Although I did not go to TCU, I like to say I’m a graduate of the Schieffer school, taught by the legend himself,” Hartung said. “Nothing makes me light up after a broadcast quite like seeing an email pop up from Bob with his observations and encouragement.”

Other journalists Schieffer mentored include Jacqueline Alemany, congressional investigations reporter for The Washington Post; Kylie Atwood, national security correspondent for CNN; and Nicole Sganga, homeland security reporter for CBS.

“And how about that kid Elizabeth Campbell?” Schieffer said. “She was just a star immediately.”

Campbell ’18, a CBS News field producer, met Schieffer while interning at Face the Nation as a TCU student. The show’s executive producer, Mary Hager, hired Campbell before she graduated. Campbell went on to work as Schieffer’s producer on coverage of the 2017 presidential inauguration.

“After that, a partnership was formed,” Campbell said. “We’ve done pieces over the years together on everything from Jan. 6 to the World Series to Jimmy Carter.

“The real lessons Bob has shared are the ones about how you approach being a journalist — the idea that you have a responsibility to the truth even when it’s uncomfortable or that sometimes the simplest questions can get the best answers.”

Early Years

At TCU, Schieffer majored in journalism and English, worked as sports editor of the TCU Daily Skiff and got a full-time job at KXOL, a local radio station. He covered the police beat, reporting on the scene of car wrecks and crimes.

“I may be the only reporter who ever got carded at a murder scene,” he said. “There was a gangster bombing out at a place called the Penguin Club.” Schieffer showed his press card, but police stopped him at the door; at 20, he was too young to enter.

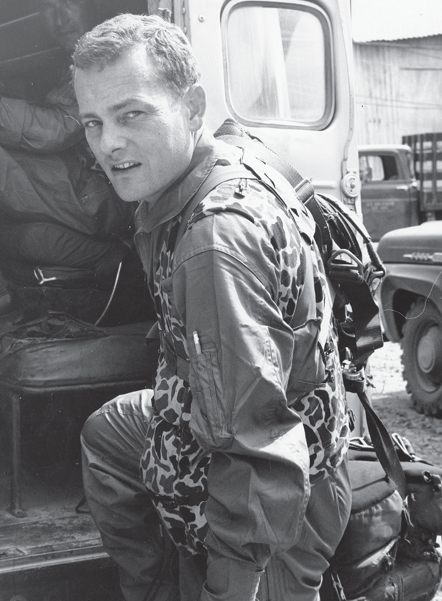

The Fort Worth Star-Telegram sent Schieffer to Vietnam, where he flew with a U.S. military pilot and reported on Texas soldiers. Courtesy, Fort Worth Star-Telegram Collection, UTA Special Collections

Following graduation, Schieffer joined the Air Force; he had been in ROTC, an experience he credits for life-changing lessons in leadership and responsibility.

After three years of military service, he returned to Texas to work as the night police reporter for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. He dictated reports over the phone to editor Phil Record, whose guidance, he said, helped him sharpen his storytelling skills.

On Nov. 22, 1963, the day President John F. Kennedy was assassinated, Lee Harvey Oswald’s mother phoned the Star-Telegram asking for a ride to Dallas. Schieffer answered the call, enlisted a ride from another reporter and sat in the back seat with Marguerite Oswald, getting an exclusive interview. He also distinguished himself by reporting from Vietnam during the war, sending back stories about local soldiers.

“The Star-Telegram was very good to me,” Schieffer said. “They gave me a job. When I came back from the Air Force, they sent me to Vietnam [to report], which was kind of a turning point in my career. And then they found me a wife. I don’t think they did that for everybody.”

Family Life

George Ann Carter, the wife of Star-Telegram publisher Amon Carter Jr., played matchmaker for the young journalist. She called Schieffer after he became an anchor at WBAP-TV to ask if he was single. She then invited him over to introduce him to Patricia Penrose ’61, a society columnist for the Star-Telegram.

“I got up my courage and showed up there on a Sunday afternoon and there was Pat. And about two months after that, we decided to get married,” Schieffer said. “And when my daughters came along, I had to tell them many times, ‘Girls, this is not how you do it. We just got lucky.’ ”

Bob Schieffer and his wife, Pat, read in their Washington, D.C., home. The couple met while he was an anchor at WBAP-TV and she was a society columnist for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram.

The pair began talking politics on their first date and never stopped. A couple of years after they wed, Schieffer got a job offer in Washington, D.C.

“I said, ‘I’ve wanted to live in Washington all my life. When do we go?’ ” Pat Schieffer said. “I knew that he was ambitious and whatever he did, he would do well.”

The Schieffers moved in 1969 and embraced life in the nation’s capital. Once there, Schieffer stopped by the CBS offices, inadvertently slipped into an interview slot intended for a different Bob and was offered a reporting job. (Robert Hager went on to a career at NBC.) Over the next four decades, Schieffer interviewed every president from Richard Nixon to Joe Biden.

The couple enjoyed meeting politicians, diplomats and bureaucrats, Pat Schieffer said. Their two daughters shared their interest in politics, interning as congressional aides.

“I couldn’t have had the career I had, I couldn’t have had the life I had if it were not for Pat,” Schieffer said. “When I was writing all those commentaries, which I would do at the end of Face the Nation every week … I would say, ‘I just can’t think of anything to write a commentary about,’ and she would say, ‘Well, you’ve been ranting all week about this or that. Why don’t you do that?’ ”

Daily News

Schieffer, who retired from Face the Nation in 2015, subscribes to print editions of The Washington Post, The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal — and reads them in that order. Other media habits include watching the CBS Evening News and watching CNN throughout the day.

“Sometimes I agree with their coverage and sometimes I don’t,” he said. “But I think those are all reputable publications and television; they have editors, and they don’t go with wild stories that nobody has checked out.”

Schieffer’s 2017 book, Overload: Finding the Truth in Today’s Deluge of News, explores the problem of an overabundance of news sources. The book shares insights from some 40 journalists and news executives.

“I’m really proud of that book because we talked about things like the decline of newspapers and how we’ve switched … to a situation where we’re so overloaded with news, we can’t sort it out,” he said. “What newspapers used to do is they were the curators of the news; they told us what was important. … Now everybody brings their own facts to the argument.”

Schieffer said journalists can combat that loss of confidence among audiences by avoiding mistakes and immediately correcting any that are made. But he remains concerned that people who can’t afford news apps aren’t getting the same information as those who can.

“This is probably the most dangerous period in American history since at least the Cuban missile crisis and maybe beyond that,” Schieffer said. “Making sure people are properly informed and understand if the information is correct or if it’s not — that’s one of the reasons journalism schools are so important now.”

Bob Schieffer subscribes to the print editions of the The Washington Post, The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal. He reads them in that order.

Journalism Then and Now

Schieffer learned how to be a journalist from on-the-job mentors. But today, he said, with fewer traditional newspapers and more digital jobs, that’s not always possible.

“A lot of these kids are coming out of college and headed to a job where the reporter will actually file the story before an editor has looked at it,” he said. “What journalism schools today do is critical and is, quite frankly, more important than it was when I was in school.”

Having TCU’s Bob Schieffer College of Communication named for him in 2013, he said, is his “single most treasured recognition.” The honor came nearly a decade after TCU’s department of journalism was named for him in 2005.

“I’ve won a lot of journalism prizes over the years, and that’s great, but that people would actually choose my name to put on their journalism school — sometimes I still don’t believe it,” he said. “I have tried to take as active a role as I can in helping people get to know about the school and what it does.”

He hosted the annual Schieffer Symposium at TCU from 2005 to 2015, bringing such media luminaries as Bob Woodward and Norah O’Donnell to campus. Schieffer reprised the symposium in honor of the 10th anniversary of the Schieffer College’s naming in November, returning to TCU with a panel of top national journalists, including Omar Villafranca ’00, a CBS News correspondent.

Schieffer credited Kris Bunton, dean of the college, for assembling the faculty and doing the work that has made the Schieffer College what it is today, and Chancellor Victor J. Boschini, Jr. for the university’s trajectory.

“We are proud as a college to be named for Bob Schieffer because he is a person of integrity who sets an example for all of our students who are training to be professional communicators,” Bunton said at the Schieffer Symposium in November.

In 2016, Bob Schieffer, an honorary Trustee, and Pat Schieffer, who served as a TCU Trustee for 30 years, endowed a scholarship in honor of Schieffer’s mother. The Gladys Payne Schieffer Scholarship covers all educational expenses for up to four students a year.

“During the 21 years I have been fortunate enough to observe TCU,” Boschini said, “Bob and Pat have both been stalwart supporters — making an impact on just about every area on campus.”

Processing Through Paint

At 87, Schieffer is still embarking on firsts. His debut one-man art exhibition, “Looking for the Light,” was curated by presidential historian Michael Beschloss. The New York Times covered its April opening at American University in Washington, D.C. The show features 25 of his 30-by-40-inch oil paintings, mostly of current events.

For the last few years, Schieffer has started each day with coffee and a paintbrush. Painting is not relaxing, he said, but helps him process the news. Schieffer compared his paintings to the commentaries he wrote for Face the Nation.

A lifelong artist, Bob Schieffer began painting in earnest during the pandemic. A portion of his dining room serves as a studio where he works on portraits, including this one of the late U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

“He gets very intense,” Pat Schieffer said. “These ideas sometimes flow so fast that he almost can’t get it all down.”

The lifelong artist’s devotion to painting deepened as the Covid-19 pandemic hit the U.S. The crisis became personal for Schieffer when Hartung, his former assistant on Face the Nation, contracted the virus in March 2020 while reporting in Seattle on the country’s first outbreak. Schieffer reacted by painting Americans being put into ambulances.

As the news cycle continued, Schieffer painted George Floyd. He depicted statues of Confederate generals plastered with Black Lives Matter posters, and he captured the events of Jan. 6, 2021.

“The Capitol is the center of our politics, and that people would treat it like that … that was a terrible day,” Schieffer said. “And I kept thinking, ‘What if my daughters were still working up there?’ ”

Some of Schieffer’s paintings offer historical context, including his composition featuring George Washington, Franklin Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln. “For all the difficulties of going through the Covid era, each of those presidents had far greater problems to resolve,” he said. “They didn’t try to change history or erase history or gloss over history. They just met the problems head on.”

At the center of the exhibition is “The Poet,” his painting inspired by Amanda Gorman’s reading of “The Hill We Climb” at the 2021 presidential inauguration. Schieffer was especially moved by the poem’s last lines — “For there is always light, if only we’re brave enough to see it, if only we’re brave enough to be it.”

His painting shows the youth poet laureate in profile, wearing a bright yellow coat against a purple background. The art bears the inscription, “And youth shall lead them.”

“The best and most useful gift we can pass on is an accurate history, which is why I think journalism is so important,” Schieffer said. “Free speech and an accurate history are as important to democracy as the right to vote, and we must never forget that.”

An exhibition of Bob Schieffer’s paintings, including this portrait of youth poet laureate Amanda Gorman, is on display at American University in Washington, D.C. He was inspired by her poem “The Hill We Climb,” which she read at President Joe Biden’s inauguration in 2021.

Your comments are welcome

2 Comments

I enjoyed the story on Bob Schieffer in the Summer 2024

TCU Magazine. Bob and I were TCU fraternity brothers

in Phi Delta Theta in the late 1950’s. I graduated in 1961 and Bob in 1959. He had much success as a radio and TV

reporter and turned into a great journalist. But what really impressed me about him was his friendly demeanor and

ability to relate to his friends and colleagues. So, thank you

for featuring him and I’ll try to reach out to him soon if

I can locate his phone number or text information.

Vance Kent Apple Frisco Tx

Always love hearing the Schieffert story. A true representation of wha and what defines Texas Christian University.

Related reading:

Features

Dance of Dynamics

Business management students learn that how you move sends a message.

Features

The Business of Buzz

TCU students are learning to craft social media strategies that win followers and build brands.

Research + Discovery

Deeper Compassion

Joe Hoyle’s capstone project examines the impact of empathy training on scuba volunteers.