Songs of a Visionary

Deborah Simpkin King creates transformative concert experiences.

Choral conductor Deborah Simpkin King ’76 doesn’t remember a life without music.

King’s father, an aeronautical engineer, played piano all his life. Her mother, a writer and homemaker, studied cello in college.

As for her singing, “the story precedes my memory,” King said. “Apparently, I just always did [sing], even as a tiny child 2 and 3 years old.” She joined choir in junior high and never looked back.

King is artistic director and founder of the Schola Cantorum on Hudson, a nonprofit organization that brought Mending the Sky to stages in New York and New Jersey. Two years ago, King conducted the East Coast premiere of “Pietà,” an oratorio by John Muehleisen, with the Schola Cantorum on Hudson. Courtesy of Deborah Simpkin King

King is artistic director and founder of the Schola Cantorum on Hudson, a nonprofit organization that includes Ember, a semiprofessional ensemble that performs in Manhattan and northern New Jersey. She is also founder of a catalog of contemporary, post-premiere choral music.

The conductor began laying the foundation for her musical vision at TCU. “In order to be the kind of conductor I wished to be, I needed to understand the instrument,” King said. “My first degree is in voice, and I continue to love singing.”

Then King earned a master’s degree in music education and conducting, and a doctorate in musicology. The combination has given her a substantial reservoir of knowledge. “Whether it’s working with an individual voice or a collection of voices, when a problem presents itself, I just let it speak to me and I go to the reserve of what I know,” she said.

King has an affinity for new music. Her concerts often include compositions outside the canon that are difficult for singers and unfamiliar to audiences. Some pieces are “challenging to the ear … but I always try to provide the audience a way into the score and then a way out of it,” she said. She has added dancers to performances and invited audiences to tweet about concerts.

The conductor is partly driven by her love of voice, that “most human and God-given” instrument. But there’s also something else — her belief that music can transform the human spirit. As wonderful as music is as an end in itself, she said, “I also look at it as a powerful vehicle for reaching into our hearts and souls in ways that words cannot.”

From ‘brass tacks’ to ‘something greater’

Choral music is about passion and aesthetic, but it’s also about breath, pitch and enunciation.

“Just because we make musical sound doesn’t mean we make a transformative experience,” King said. She talks with her church choirs “about reporting the notes or delivering a message. There’s a real difference.”

Kent Tritle, organist and director of cathedral music at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City, knows King through his work in the New York Choral Consortium.

A person can have musical knowledge and musicianship, Tritle said, but King has several skills others lack: She’s “centered, serene — but capably energetic.”

“She believes what I believe: that you do not get the best from people by talking down, by berating, by yelling,” Tritle said. “You get the best sound from your people by being calm, being focused, being energized. You’re being positive, you’re giving positive images, speaking positively, believing they can do what you’re asking them to do.”

Part of music making is getting down to “brass tacks, and part is metaphysical,” Tritle said. “She creates a path [singers] can pour themselves into and become something greater.”

King has brought in composers to help smooth that path, creating what American composer John Muehleisen called “the triad of composer, conductor and performers.”

Ember performed Muehleisen’s oratorio “Pietà” a few years ago, and his involvement in rehearsals was “a mountaintop experience.”

“There’s a wonderful sort of thing that happens when you bring in a composer,” Muehleisen said. “Once you’ve composed a work and you’ve put it out there like a message in a bottle, whoever does it, it’s no longer yours. Whoever does it, it’s theirs to understand and interpret.

“One of the advantages for performers of having access to a composer is to get more of the composer’s intent.”

Last November, King performed Muehleisen’s newest oratorio, “Who Shall Return Us Our Children? — A Kipling Passion,” making her one of only two conductors to perform both works.

Message with might

King chooses music with a purpose and a message, said Laura Greenwald, director of vocal studies at Caldwell University in Caldwell, New Jersey, and a member of King’s nonprofit since 2009.

“And then she pays attention to the detail to make sure we are performing it as accurately and beautifully as possible,” Greenwald said. “I cannot look at the variety of the music she looks at and see what she sees in it. After we perform it, I can. But not before.

“Some people are leaders, and some are followers,” Greenwald said. “Deborah is a leader. She has foresight. … It’s not just the drive, but the ability to see a destination.”

Choral conductor Deborah Simpkin King ’76 is passionate about using innovate ways to bring audiences together with choral music and choral composers. Photo by Beatriz Terrazas

King’s repertoire includes messages of compassion, kindness, and social and environmental justice. A recent season themed “Our Mother Earth” focused on stewardship of the planet.

The first concert was called “Canopy of Life” and she commissioned a multimedia presentation about trees. When Hurricane Sandy wreaked havoc two weeks before the concert, the photographer included photos of tree damage.

“People were weeping,” King recalled.

The 2016-2017 season focused on human ingenuity and paid tribute to her father, Bill Simpkin, who invented and patented Simpkin HiEff Power, a clean energy technology. He died in 2016.

“The final concert in this season’s series is titled ‘All Things Possible,’ and it espouses the belief that when needs arise, the indefinitely renewable resource of human ingenuity always holds the capacity for producing the solution,” King wrote in a guest column for The Montclair Times in New Jersey.

Carol Sargent, a soprano with King’s nonprofit since its inception in 1995, recalled one rehearsal for this series. Two-thirds of the way through, “we got to a piece called ‘Do Not Be Afraid,’ and I couldn’t sing it,” said Sargent, explaining she was overcome with emotion by the “cumulative effect of the words and the music, how she had put it together. … It was remarkable.”

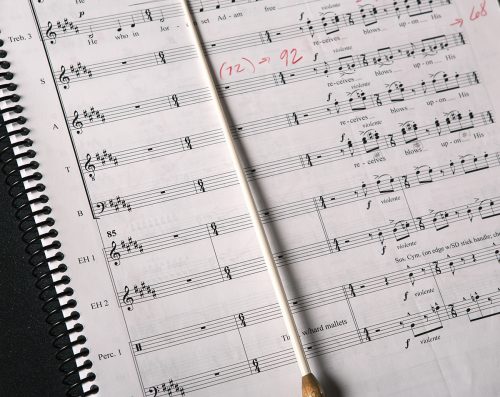

A page from the score for John Muehleisen’s oratorio “Pietà,” with annotations by choral conductor Deborah Simpkin King ’76. Photo by Beatriz Terrazas

‘Modern-day prophets’

King’s advocacy for living composers — those “modern-day prophets” with “the ability to vision and envision” — began as a lobbying effort for a composer whose work she had premiered.

For years afterward, King tried to help the composer get a second performance of the work with “not a nibble” of response. This, she said, is “the perpetual problem composers all know, and performers tend to be oblivious of. … There is a certain cachet to the first performance.” After that, compositions can languish.

In 2009, King launched a catalog of post-premiere works vetted by a pool of top-tier conductors. Conductors can see score samples online and purchase performance rights from the publisher or composer.

“Works can be submitted for Project : Encore if they have received their premiere and have not gotten significant attention beyond that,” King said. There is no fee to submit, and about half of all submissions are accepted.

Deborah Simpkin King is the founder of a catalog of contemporary, post-premiere choral music. Photo by Beatriz Terrazas

“It’s a whole new paradigm of music evaluation and promotion,” King said. “This is the one thing that I know will outlive me.”

Meanwhile, King continues to try to change the world, one choral performance at a time. “The arts can enliven those parts of us that we tend to disenfranchise,” she said, “those parts of the human condition, I believe, that connect all of us.

“There are some things that are the same within us, and when we come together in ways that are core to the human experience — I’m convinced … there would be no war,” King said. “That sounds very simplistic, and we’ll never totally get there, but I think that to move us in that direction is always a goal, and the arts can help. That’s why I do what I do.”

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related reading:

Alumni, Web Extras

TCU Magazine Podcast: Deborah Simpkin King

Deborah Simpkin King ’76 talks to host James Creange ’17 about the impact of music, its cathartic powers and the way it connects people.

Features

Frog Corps’ Spirited Singing

The all-male choral group aims to leave a legacy through song.

Features

Our Marching Band, the Pride of TCU

In its 111th year, the band still practices hard, relies on teamwork and performs with passion.