Finding the real child

A monumental research project at TCU’s Institute of Child Development may offer permanent healing to broken children and their families.

Finding the real child

A monumental research project at TCU’s Institute of Child Development may offer permanent healing to broken children and their families.

|

|

|

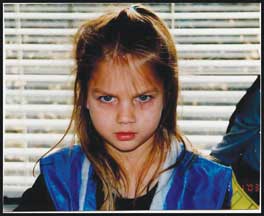

The physical changes in Kristen’s visage from age 4 (top) to age 6 (bottom) reflect the emotional and mental healing that therapy brought about. |

The breaking point for Stacie came when her 4-year-old adopted daughter, Kristen, shoved her 2-year-old sister down a flight of stairs, then ran down and repeatedly stomped on her.

“I called my husband and told him to meet me at the psych ward of Children’s Hospital (in Dallas),” Staci remembers. “I was afraid of what I would do, and I knew I could not handle Kristen anymore.”

Less than five years earlier, Stacie and husband had adopted two Russian babies, 8-month-old Kristen and 23-month-old Caleb, after giving up on having children of their own. The couple knew that children from foreign countries often came with emotional baggage, but they felt capable of handling any problems that arose. So capable that they adopted another girl, Ava, from Russia a year later.

From the beginning, baby Kristen would arch her back when rocked or held. She disliked snuggling, and only seemed happy when put down in her bed. Stacie chalked it up to attachment disorder, as is normal with newly adopted children, and determined to limit outings, over-stimulation and large gatherings like Christmas parties.

Soon after the toddler years, “handling” Kristen meant surviving outbursts of kicking, screaming and growling. It meant never leaving her alone with other children, not even her two siblings. Entertaining dreams of rocking the child to sleep was a waste of time.

Stacie accepted that her daughter was a statistic — the one in five adopted children diagnosed with behavioral disorders each year. Eventually the uncontrollable anger reached critical mass, and the desperate family considered institutionalizing the little girl.

There are thousands of families like Stacie’s — loving couples who just want to be successful parents to their adopted kids. And increasingly, these parents are passing the limits of their abilities.

The fortunate ones are finding TCU’s Institute for Child Development (ICD). Started in 1999 as a research project called Hope Connection by psychology Professor David Cross and then-graduate candidate Karyn Purvis ’97 (MS ’01, PhD ’03), the ICD is discovering groundbreaking answers to why children who suffer severe abuse and neglect in their earliest years have so much trouble developing normally.

It’s turning those answers into a therapeutic model that is drawing excited child development professionals worldwide to the small office suite in Winton Scott Hall where Purvis, now ICD director, and Cross are quietly creating miracles.

Kristen’s mother didn’t head for the hospital that day. She called Purvis, whom she had met when her son attended one of Hope Connection’s summer camps for adopted kids. Stacie saw miracles at the camp, life-changing moments that dramatically altered the fate of entire families. Now she needed one for Kristen.

|

Targeted Amino Acid Therapy: oral supplements taken under the supervision of a medical practitioner to balance inhibitory (those that relax the body, such as GABA, serotonin and glycine) and excitatory (those that signal fight or flight responses, such as epinephrine, norepinephrine, dopamine and histamine) neurotransmitters. It corrects neurotransmitter levels of the brain. |

When a newborn enters the world, the five senses are the baby’s only connection to this new existence. As the child is cuddled and fed, circuits in the brain known as neurons begin to connect, enabling the infant to make sense of his or her world. A dearth of sensory input causes the brain to wither or grow incorrectly. Over time, this developmental void can escalate and the chemical balance skew, triggering severe emotional and developmental problems.

Babies in foreign orphanages are generally laid in a crib with a propped bottle. Their only human contact is when a nurse changes a diaper or props a new bottle. Physical abuse is common. To compound the problems, prenatal care is likely nonexistent and many children arrive saddled with fetal alcohol syndrome or malnourishment, not to mention various forms of autism or other mental deficiencies. These babies eventually become that “one in five” as their crippled minds search for ways to cope. Without help, such deficiencies put children like Kristen on a clear trajectory: a life of mental illness that frequently ends with institutionalization or incarceration.

|

Sensory rich: An environment heavy in sensory experiences. Activities that are a natural component in a child’s first years of life – snacks, crafts, games, reading – are absent in most children who have suffered early neglect and abuse. |

To say the miracles started with the right connection is no cliché. A serendipitous meeting in 1998 between Purvis, Cross and an adoptive mom resulted in Camp Hope, a three-week day camp that focused on the special needs of behaviorally at-risk children. With a small grant from Fort Worth’s Child Study Center, the first camp was held in 1999.

Purvis, Cross and other participating professionals stood at the door of the downtown center as 10 children between the ages of 3 and 9 marched in.

“I thought we’d have a good time, learn from the children, find ways to chip away at some of their losses,” Purvis says today, “but I had no idea this chrysalis would open and we’d find what we call now ‘the real child’ hidden under all these maladaptive strategies that kids have when they don’t feel safe.”

The camp “bathed” kids in a structured, sensory-rich environment through therapeutic horseback riding, swimming, planting seeds, painting and role playing. For the Camp Hope kids, it was three weeks of fun. But to the professors, university students and local child advocacy professionals who staffed the program, it was a way to research therapies.

What happened astonished everyone. On the fifth morning, one mother arrived with tears streaming down her face, reporting newfound eye contact from her child. Another said her daughter asked to be held — a first. One parent told Purvis that his adopted child said “I love you” for the first time. Many of the adoptive parents had all but discarded these visions of “normal” family life.

“There was this amazing thing going on that was, at the same time, terrifying,” Purvis says. “I didn’t understand what happened and didn’t know how to keep it alive.” She consulted with experts at Harvard and other child psychology specialists. No one could explain what happened. “What we believe now is in this attachment-rich environment, the kids have brain chemistry changes, and with that, their language and behavior changes.”

Still another discovery: Staffers gathered saliva samples through “spitting contests” held three times during the day to test cortisol (a natural stress indicator). They found during the second week of camp that the high cortisol levels were down by half.

“These physiological data paralleled our behavioral data and confirmed our insight that as the children felt less anxious and afraid in the context of the camp environment, they had dramatic positive changes in social and attachment behavior,” Purvis says. After five days of consistent sensory activity and learning, their brains were making adjustments.

In this real-life laboratory, Cross and Purvis were able to impact most of the kids, though many regressed when camp was over. For Cross, director of TCU’s Developmental Research Lab, this was the catalyst for providing more learning opportunities for parents. The team began offering parent and professional seminars on “Helping the Hurting Child” so families could apply activities and techniques at home.

Meanwhile, word was spreading through the nation’s mental health system that something extraordinary was occurring under the Texas sun. Professionals from across the country came to camp to see this singular research for themselves. Medical names like Dr. Patrick Mason, director of the International Adoption Center at Inova Fairfax Hospital; Dr. Lisa Albers of Harvard Medical School; and Dr. Dana Johnson, director of the International Adoption Medical Clinic at the University of Minnesota, watched the history-making work unfold.

Purvis, who worked from the beginning with developmental neuropsychologist Ron Federici, director of Neuropsychological and Family Therapy Associates, expanded her research by helping Federici in intense home programs for families of at-risk children. She helped supervise the home program for a Fort Worth boy — a program featured on an award-winning Dateline NBC documentary in 2003. Since then she and Cross developed their own parent-coach therapy incorporating the structure portion of Federici’s program, yet focusing “just as much on nurture as on structure,” with a major emphasis on the parent-child attachment relationship. The first Hope Connection parent-coaching therapy study was Kristen.

“Our work has confirmed that these children’s aggressive behaviors are fear-based. We see the fear, the mental illness and anger disappear when they use words [instead of physical violence and anger] to deal with the pain and fear,” Purvis explained. “We think the greatest thing we can do is create an environment where they feel safe.”

Purvis also said that with every home program she has directed, the child has eventually disclosed the root of his or her fear, be it physical abuse, suffocation, starvation or sexual abuse. “You think a kid that young won’t remember, but every one of them do.” Kristin even told of being nearly suffocated as an infant.

In 2004, Gottfried Kellerman, director of Wisconsin-based NeuroScience, Inc., read the TCU findings. He furrowed his brow at the off-kilter levels of neurotransmitters such as epinephrine, norepinephrine, dopamine, serotonin and histamine — all crucial to brain development.

“I checked the neurotransmitters at random. I had no idea they were related to behavioral issues,” he said. “But I thought if a correlation to the behavior and the neurotransmitter levels could be confirmed, we might be able to facilitate the change of certain behaviors on a more permanent level.”

Kellerman was already developing and customizing amino acid supplements, also known as targeted amino acid therapy (TAAT), for some juvenile at-risk cases. Amino acids, which turn into neurotransmitters in the brain, can be bought at any health food store. These “foods” stimulate the brain in the same way as a drug, only in a more corrective, natural manner, with fewer side effects.

“Since the brain is maturing, amino acid therapy will help the brain outgrow the problem. It stops the deterioration,” Kellerman said. “If you do nothing, the problem will ultimately get worse.”

Kellerman was astonished at the changes in Kristen’s neurotransmitter levels after completing the intense parent-coach program.

“I flew off my chair,” he said, adding that supplements are always provided in consultation with a child’s medical practitioner. “For the first time, we saw chemical changes as a result of a behavioral therapy. It was fascinating to see something change in certain chemicals that could be related to behavioral issues and physical changes.”

Depending on the severity of a child’s behavior, the concentration of neurochemicals cannot always be altered. But Kellerman is sold on the combination of supplements and behavioral therapy as a prescription for families who have lost hope.

“Psychological intervention is an absolute must,” he said. “Things have to be worked up and out.”

Amino acid therapy coupled with sound parent coaching is like a diamond dropped in the hands of parents like the Kristen’s. Unlike drugs, supplements are not a permanent fixture in the lives of children who take them.

Purvis found Kellerman’s work so promising that camp was closed for the 2004 and 2005 sessions; priority No.1 became the neurotransmitter study — yet another project untouched by any known psychologists thus far.

The study, completed late last year, explored the efficacy of TAAT — an alternative to pharmacological approaches — with 78 adopted, behaviorally at-risk children. The subjects were divided into two groups; one received TAAT in a capsule form upon initial testing for two months, and the second group was tested, then waited two months before receiving the supplements.

The treatment group showed significant improvements on four of eight neurotransmitter tests — epinephrine, serotonin, GABA and PEA — and on six of 11 tested behaviors, including anxiety/depression, thought problems, attention problems and aggressive behavior.

“These improvements,” according to the study summary, “suggest that TAAT has promise as an intervention for behaviorally disordered children.”

So stunning were the study findings that the Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine is publishing them — a major step toward helping hurt children on a national level.

Visions of a world where children with behavioral problems are no longer just stamped with a prescription for Ritalin, Paxil or Zyprexa were coming into focus.

Today Kristen is a shy, athletic and sweet 7-year-old with striking blue eyes. She plays soccer and softball and attends school and birthday parties. She giggles with her sister and argues over electronic games with her brother, as typical children in a typical family do.

Following the intense parent-coaching therapy, Kristen made even greater progress after being put on Kellerman’s supplement therapy. She is now drug and supplement free.

Families from all corners of the world are now tracking down the ICD’s phone number and begging for help.

“We get maybe 200, 300 requests a month, and it’s just David and me,” Purvis noted.

Early last summer, her three-year post as director of the ICD was made official as part of TCU’s Vision in Action initiative. It provides for Purvis’ and a research coordinator’s Early last summer, her three-year post as director of the ICD was made official as part of TCU’s Vision in Action initiative. It provides for Purvis’ and a research coordinator’s salaries, and Purvis hopes to add a couple of full-time professional positions so they can provide more training to this troubled population of adoptive families.

So far, Purvis has monitored a home program for a Romanian child in Iceland, as well as a young boy diagnosed with autism in Scotland. Adoptive parents searching for answers can learn in various seminars and programs provided.

The ICD also collaborates with institutions such as the Chaddock Residential Treatment Facility in Chaddock, Ill., the Gladney Adoption Center in Fort Worth, Icelandic Children’s Hospital in Reykjavik and the Texas Association of Infant Mental Health, all of which provide research opportunities to TCU students through internships, mentoring at-risk children or graduate work.

With the help of a professional writer, Purvis and Cross are working on a book, The Healing Parent, which is expected to be released in November, and developed a Web-based course for adopting parents (see www.fosterparents.com). Also on their wish list: an online teaching module for families and professionals.

The ICD’s goals are threefold:

1) Continue to generate knowledge and information that helps parents.

2) Create a set of model programs to disseminate to other professionals and parents.

3) Put the project on a firm financial foundation, which can be done with an endowment.

In the past year a swell of publicity has resulted in new funding from private foundations and increased awareness in the field. Even Sen. Mary Landrieu, D-La., an adoptive parent and adoption advocate, has voiced support of the ICD.

“There are often many different issues, both cultural and circumstantial, that adoptive parents and their children must work to overcome,” Landrieu said. “The Institute for Child Development provides a basis for these children and parents to learn how to nurture each other and in turn begin to grow fulfilling, lasting relationships.”

In November, Kristen answered the door of her home wearing a huge inquisitive smile and plastic buckets on her feet, then she clomped away, giggling. Her mom emerged from the kitchen with a piece of paper covered with colorful drawings and stamps.

She flipped it to the back, where the formerly tormented child had scrawled in hot pink marker, Hi Mommy, I am so glad that you are my mom. I love you, Kristen.

“She brought this to me the other night,” Stacie said. “A year ago I never, never thought I would ever see anything like this. This is the real girl.”

TCU’s Parent-Coach Therapy

So far, Karyn Purvis, director of TCU’s Institute for Child Development, has only administered a dozen intense parent-coaching therapy programs, primarily to gather research. But the ICD hopes to add several professional therapists to its staff so more families can be helped.

The intense program is a serious commitment by the family and parents to go to extraordinary lengths to make the changes needed.

First, the family is screened. An Adult Attachment Interview provides both researchers and parents a look into psychological issues, specifically things that affect the parental role. “A parent can most accurately guide the child’s steps when they’re aware of their own,” Purvis explained.

Then the parents are provided with extensive materials on sensory issues, at-risk behavior and neurotransmitters. They’re given a list of supplies to have handy, such as an egg timer, poster board, puppets and bubble gum for saliva tests. Purvis then walks them through “war simulation.”

One parent must remain no more than arm’s-length away from a child at all times, including sleeping. There are no extracurricular activities (no school, playdates, video games). The days in Level 1 follow a strict routine: The morning may include going over the child’s rules (no screaming, no hitting, using your words), a sensory activity like jumping rope or a hula hoop, role-playing with puppets (the parent might use one puppet to portray a disrespectful person, while the child uses the other to relate respectful actions and words), a nourishing snack (required every two hours), household tasks or chores, and another activity such as practicing scripts or plays that teach cooperation and compromise, listening and obeying, and consequences for poor behavior.

The afternoon follows a similar routine, all geared toward teaching the child insight into his own behaviors and feelings. The parent and child “check engines” — is it running too low, too high or just right? — throughout the day to teach self-regulation. If the child is wound up, the parent might suggest a calm activity like deep breathing or a relaxation exercise. If a conflict occurs, the child “earns” a chore, such as cleaning the kitchen floor for one minute, which grows in minute-increments if the child continues aggressive or challenging behavior. The entire day is also filled with nurturing moments like reading together, taking walks, snuggling and doing crafts. This stage, depending on the child’s age, lasts about a month.

Level 2 of the program is relaxed; the distance is stretched, though the child must be in the same room as the parent. Planned outside activities are also allowed, with achieving a balance between structure and nurture the goal. After an average of six weeks, the child may show adaptation of new behavior skills, gaining the family a move to Level 3, which involves maintenance of the routine.

Purvis said a vital difference in the ICD’s therapy program is the importance of nurture. “In building attachment between the child and a parent, a trusting relationship drives change — not force,” she said.

ICD’s Staff

David Cross, PhD, is former chairman of the psychology department and current director of TCU’s Developmental Research Lab. A foster child raised in California, he received master’s degrees in psychology and statistics as well as a PhD in psychology and education from the University of Michigan.

Karyn Purvis ’97 (MS ’01, PhD ’03), director of the Institute for Child Development, is a former foster parent and mother of three grown sons. She has been published in numerous magazines and journals, and presented at child welfare seminars almost monthly for the past four years.

Jackie Pennings (MS ’05), research coordinator, transferred to TCU in 2003 to earn her master’s degree in experimental psychology. She has a younger brother who was adopted from Guatemala.

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related Reading:

Features

A Prescription for Success

TCU’s health policy program from the Neeley School of Business trains medical industry professionals in the business of health care.

Features

Campus of the Future

TCU’s Campus Master Plan builds on the university’s vision and values.