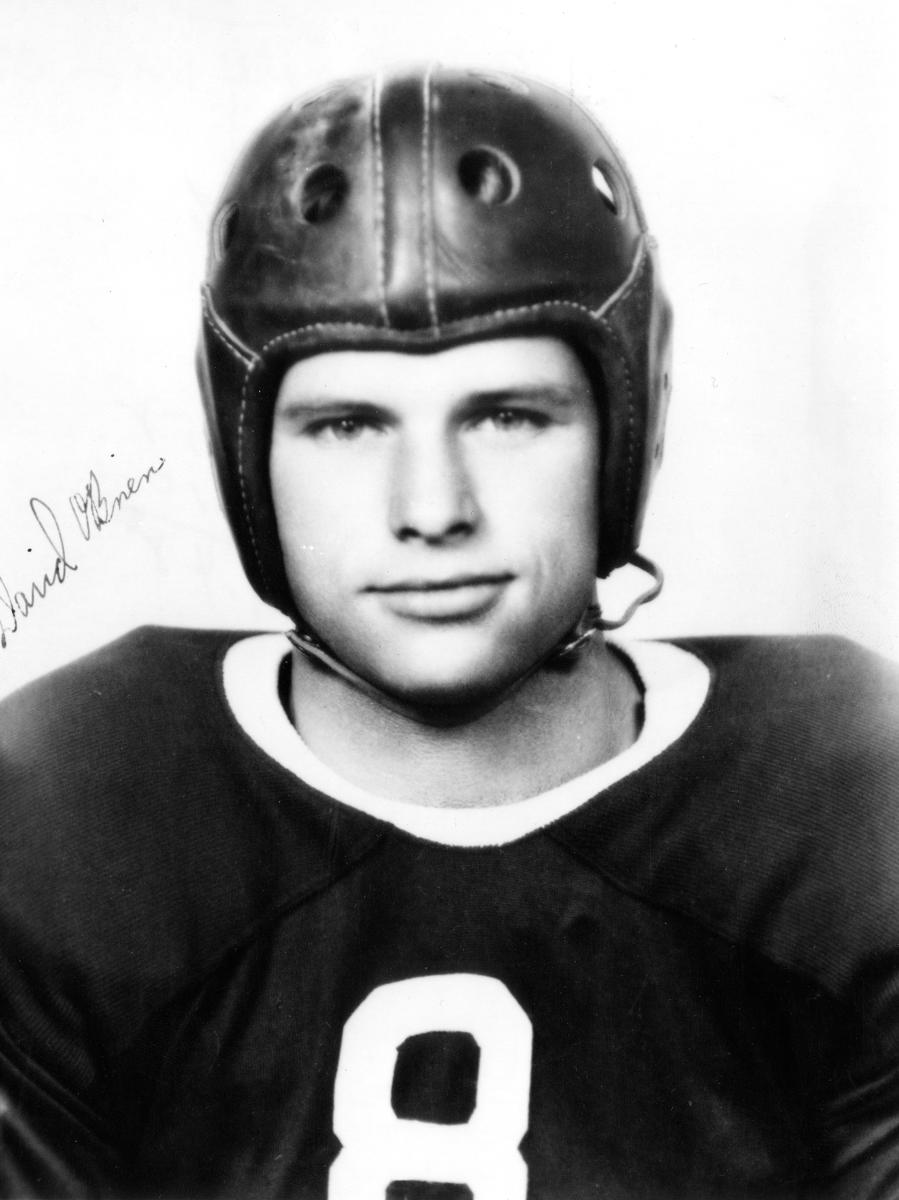

A Heisman life: Remembering Davey O’Brien ’39

For a time, he captivated a nation. The Frogs were voted National Champions for the 1938 season, and Davey claimed nearly every honor available, including the Heisman, the Walter Camp and a unanimous first-team All-American.

A Heisman life: Remembering Davey O’Brien ’39

For a time, he captivated a nation. The Frogs were voted National Champions for the 1938 season, and Davey claimed nearly every honor available, including the Heisman, the Walter Camp and a unanimous first-team All-American.

The aged pages in the two-inch thick binder crack with each turn.

The year was 1939.

Mr. O’Brien, I am scribbling a line to tell you of the surprise we had tonight when we went to the show. We were very bored with the News Reel when suddenly the announcer blurted out, “Watch TCU in this game!” We watched and there was David O’Brien tackling, carrying, passing and kicking that old football around like a real fellow. Dave, old pal, you’ve sure got something there . . . .

Dear David, By virtue of my position as Speaker of the Oklahoma House of Representatives, the high honor came to me yesterday of filling the Governor’s Chair of this State for two hours. During that time I appointed you as a Colonel on my staff. Your Commission is being sent to you under separate cover . . . .

Hello, Davey, I am a little Irish girl, about 5′ 1″. I have auburn hair, hazel eyes, am 19, and I talk about you in my sleep. I have just finished school and I like football players. Since you are such a good football player and are Irish, I have been keeping tabs on you.

The brittle book stays stored away in the home of Davey’s son, David O’Brien Jr., the oldest of Davey’s three children. Somewhere are at least eight more books, each filled with clippings, note and keepsakes from that moment in time.

In a way, they all say the same thing. For a time, Davey O’Brien ’39 captivated a nation.

“We gave the Davey O’Brien Foundation everything, but I wanted to keep this,” said the 55-year-old O’Brien. “By reading all the fan letters, you can tell what people really thought of my father.”

The younger O’Brien got his Daddy’s eyes, blue as sky after a good rain. And at 5 feet, 7 inches, he got every bit of Davey’s height, too.

Before a degree from Tulane and a few graduate courses at TCU, O’Brien ran track and led cheers for Fort Worth’s Paschal High School. He played football through junior high, then during a summer language camp in Monterrey, Mexico, he wrote a letter to father Davey, the letter buffering the tiny fear he felt of telling one of the greatest collegiate football players of all time that his son didn’t share the same passion.

“He wrote me back saying that whatever I decided to do, he would respect my decision,” said O’Brien, director of Housing Opportunities, a private not-for-profit Fort Worth firm providing housing counseling and education for the underserved. “He never put pressure on us to follow in his footsteps. In fact, he was a very modest person when it came to his achievements. If people wanted to talk about football, he’d talk about it, for hours if a person wanted. I’m sure he had some points of vanity, but his athletic prowess wasn’t one of them.”

Davey passed away in 1977, after a seven-year battle with cancer. He was only 60. That was too soon for most people. “He liked to think that anyone could do anything he or she wanted to; he really equated hard work with success,” O’Brien said. “With cancer, he thought if you fought hard enough, you could beat it. But the downside of that is he never got to the point where he said, ‘Look, I’m going to die, and here is what I want to say.’ ”

Davey O’Brien never really knew his father. The year was 1920. His parents had divorced when he was a toddler. His mother, Ella Mae Keith O’Brien, who ran a private school for public speaking, raised Davey and his older brother with the help of her brother, Dallas florist Boyd Keith, who also served as the financial director of the Juliette Fowler Home for boys.

The family was most likely upper middle class, living in a handsome two-story home in what was then the prestigious Lakewood section of Dallas. And while Davey attended public school, he found his best friends on a field behind the Fowler home.

There, he met I.B. Hale ’39, the future TCU All-American lineman, and Rusty Cowart ’40, both orphans from the home.

“You couldn’t tell him apart from the rest of us,” Cowart said in a 1977 Dallas Morning News interview. “We’d eat lunch together at school, and he knew that all a Home boy had was a peanut butter sandwich. He would split his Hershey bar and milk with me.”

Over time, the boys moved from playing on a sandlot Gaston Avenue Bulldog team to the Wildcats of Dallas’ Woodrow Wilson High School. The 150-pound O’Brien and the massive 220-pound Hale were good enough to star as sophomores in 1932, when the Wildcats lost in the state quarterfinals to Fort Worth Masonic Home, 40-7.

O’Brien committed one of the few mistakes of his football career that day. Masonic Home had exploded for two quick touchdowns to break open a close game, 27-7. On the ensuing kickoff, O’Brien allowed the ball to land in the end zone without downing it.

An alert Masonic home player covered the ball for a touchdown, making it 33-7 at the half. In later years, O’Brien said he never forgot the embarrassment of that day.

The Fowler Home, like TCU, had strong ties to the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). The players there usually moved on to Woodrow Wilson, a fact that didn’t slip by TCU’s football coaches. In the next two years, O’Brien developed into an all-city, all-state and all-Southern player, as did Hale.

And in their junior years, the two received a visitor from the TCU football program. It was Leo “Dutch” Meyer.

The eleven boys on the edge of becoming men had come from Breckenridge, Panhandle, Dallas, Sulpher Springs and other farther-out places.

The year was 1938.

They were all mostly poor. America was coming out of her Depression; they all felt grateful for the privilege of college, and playing football for Texas Christian.

The underclassmen among them lived in Clark Hall, where Sadler Hall now is, and the uppers roomed in Goode Hall, where the present-day Clark Hall stands. They cleaned offices in the Administration Building in the evenings and on weekends to earn room and board.

With no cars among them and little pocket money, there wasn’t much to do. To ride a bus into downtown Fort Worth and see a show was an exceptional day. Most hot afternoons, the teammates spent practicing for the weekend’s coming game.

To preserve what little grass there was in Amon Carter Stadium, scrimmages were held underneath the stands, where both horned frogs and sticker burrs were abundant. Two metal doors at the south end of the stadium gave way to the football locker rooms and offices. Above the doors were etched two Latin phrases, still there today.

The first is Mens Sana in Corpore Sano … a sound mind in a sound body. The second, Crede Quod Habeus et Habes … believe that you can and you will. On a still day, when the wind blows just right, you can almost hear Dutch Meyer firing up the 11 as they walk from the lockers to the field on game day … Put on your hats, boys. I want to see blood today.

It was here that the 1938 team laid the foundation for a national championship, and that Davey became a national hero.

Forrest Kline remembers those days. So does Connie Sparks. The two, along with Don Looney, are the only three left of the 11. Kline started at guard for the Frogs, the heaviest man on the squad at 248 pounds. Sparks started for the varsity squad “A Team” as a sophomore and led the conference in scoring with 60 points.

That 1938 team was loaded with great players, they both agree, but none more so than David.

“He was a tough little nut,” said Connie Sparks ’41, who played fullback for the 1938 team. “Dutch was pretty young and gruff then, and he never bragged much on Davey until his later years. But he must have had great confidence in Davey as a quarterback. Dutch gave us a game plan, and we always had some special plays. Then, on game day, he turned it over to David.”

O’Brien for his first two seasons at TCU played in the shadow of “Slingin’ Sammy” Baugh ’37, who had led the Frogs to Sugar and Cotton bowl victories — and arguably a national championship in 1935.

In 1937, O’Brien’s time came. He played all but 14 minutes of the season, yet the Frogs finished 4-4-2. There was a weakness in O’Brien’s game — the long pass.

“Up to his senior year, Davey was a fine short passer, but I guess you would call him mediocre on the long ball. But he worked like the devil on it between his junior and senior seasons,” Meyer said in one interview. “During his junior year, I made the statement that we would have had several more touchdowns if O’Brien could have hit the long pass. He did hit them his senior year.”

Along the way to 19 touchdown passes his senior year, O’Brien smashed almost all of Baugh’s records, throwing for 1,733 yards and catching the attention of typewriter ribbons across the nation.

Though he preferred to be called David by his teammates and friends, “Lil’ Davey” was born in newspapers, slaying a season of Goliaths and earning a spot in the Sugar Bowl against Carnegie Tech. At halftime of that game, the Frogs trailed, 7-6. Meyer asked if any of the players had something to say. Finally, Davey stood up.

“It was the only time Davey every did anything like that,” Meyer said years later. “He calmly told the kids to keep their poise and play like they knew how to play, and they’d win the game. That was all, but it was enough. We won, 15-7.”

The Frogs were voted National Champions for the 1938 season, and Davey would claim nearly every honor available: the Heisman, the Walter Camp, a unanimous first-team All-American.

After the Heisman was announced, Fort Worth Star-Telegram publisher Amon Carter — the school’s greatest community ally — phoned the award’s benefactor, the Downtown Athletic Club in New York, and asked, “What kind of parade you folks planning when Davey comes up?”

With no ticker tape parade in sight, Carter planned and paid for the next best thing. A troupe of mounted and whooping cowboys. A sparkling stagecoach pulled by six white horses. Paul Whiteman and his orchestra. And in the carriage, Carter and Davey, both in boots and 10-gallon hats.

The morning after the ceremony, New York newspapers praised Davey’s humble acceptance speech.

“I am certainly appreciative of the high honor,” Davey began, “but I feel I must give credit to the men who made me; to Coach Dutch Meyer who taught me all I know, to his assistants, to those great linemen, Ki Aldrich and I.B. Hale . . . . I am not much at speaking so cannot begin to tell you how much it all means. But I hope this will help.”

Yet, the most telling remark about Davey came from his mother, Ella Mae.

“At first I was afraid that Davey might be hurt, because he is so small compared with the other players,” she told the crowd of 1,200. “But gradually I came to realize that defeat hurt my boy more than any physical injury.”

Davey was hurting. The year was 1940. He was at the end of his second and last season in the NFL, playing for the league-worst Philadelphia Eagles. In two seasons, the team won only two games. Statistics show that Davey ran the ball, or ran for his life, 104 times in the 1939 season.

After that first season, Davey and I.B. Hale applied to and were accepted by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Training would begin the day after the 1940 season ended.

O’Brien’s last game occurred against the league-leading Washington Redskins, led by “Slingin’ Sammy” Baugh ’37. Papers predicted an unheralded battle through the air, as TCU had introduced the short pass to the football world.

The one-on-one shootout never really happened; Washington needed the game to clinch its division title and chose to play a conservative game on the ground. But that didn’t stop Davey. Washington led the game 13-0 in the fourth quarter. With little left to lose, O’Brien went solely to the air. The befuddled Redskins watched as the hapless Eagles went 98 yards for a touchdown, all on Davey’s arm.

One series later, Philadelphia again got the ball on their own 31. Again Davey marched down the field, throwing whenever possible. The fairy tale ended on Washington’s 22-yard line, with the Skins knocking down Davey’s final pass.

As Davey walked off the field for the final time, he was greeted with applause and ovation from Washington’s 30,838 home fans. Davey had thrown 60 passes, completing 33 for 316 yards. In a day of ground-oriented offense, he had set a world record.

“David just didn’t have the horses that year,” said Baugh, now retired and living on his West Texas ranch in Rotan. “But, hell, I knew he was going to come out and throw a bunch of short passes. Dutch had taught me and David how to pass at the same time. I just didn’t think he was going to throw that many.”

Davey left for the FBI the next day, trading a $10,000 salary and a share of gate receipts for a respectable $3,200 as a government agent. David O’Brien Jr.’s eyes seem bluer than when the conversation about his father began.

It’s a warm day in January, 23 years after Davey died, with the last part of his life less chronicled than the first. He worked for the FBI for 10 years, quickly gaining notice as a tops marksman and serving on its national pistol team. In 1950, he enlisted his TCU geology degree and entered the Texas oil industry, working for several Dallas oil firms before starting his own.

The list goes on.

He married twice, first to his TCU sweetheart, Frances Buster ’40. He left behind his second wife of 20 years, Janie; three children, David Jr., William and Sally O’Brien ’71; and three stepchildren.

O’Brien’s bout with cancer wiped out his savings and insurance and left his family with a large debt. Teammates say that Looney, a wealthy oilman and arguably O’Brien’s favorite receiver on that 1938 team, was one of the greatest contributors to a fund to help the family.

Still, Davey died a rich man.

“We used to always go to the games, and we went one time when the Frogs were losing 63 to zero,” O’Brien recalled. “My stepmother said, ‘David, we don’t have to stay until the end.’ My father replied, ‘I’ve stayed until the end when we were beating teams by three touchdowns. I can’t leave now when they’re getting drubbed.’

“I think my dad simply had leadership qualities and a certain charisma that wasn’t studied or strived for. “It’s just who he was.”

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related reading:

Sports: Riff Ram

Why Max Duggan Chose TCU

The quarterback from Council Bluffs, Iowa, led TCU to its first College Football Playoff appearance and is a finalist for the Heisman Trophy.

Sports: Riff Ram

Heisman finalist now a hall of famer

With 5,387 career rushing yards, LaDainian Tomlinson ’05 helped usher in a new golden era of TCU football. This fall, the College Football Hall of Fame enshrined him.