February 16, 2016

The Geography of Heart Disease

Two TCU faculty are showing how cardiovascular disease spreads across Texas.

Sean Crotty, left, and Kyle Walker are both assistant professors of geography. Photo by Carolyn Cruz

February 16, 2016

The Geography of Heart Disease

Two TCU faculty are showing how cardiovascular disease spreads across Texas.

Using geography and big data, Kyle Walker and Sean Crotty are showing how cardiovascular disease, which is the leading cause of death in Texas, spreads across the state.

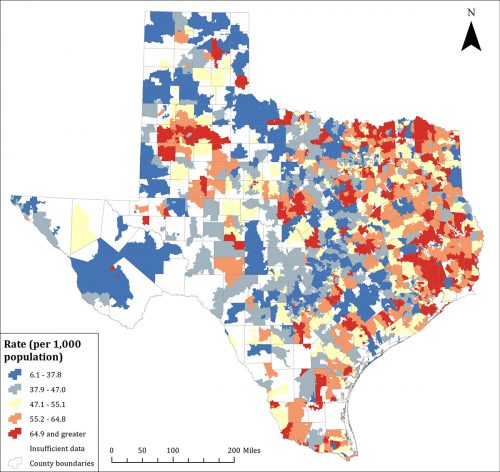

Texas Heart Disease Hospitalization by ZIP Code: Kyle Walker and Sean Crotty’s geographic distribution of age-adjusted hospitalization rates from 2006 shows high rates (red shades) in East and Northeast Texas, the Rio Grande Valley and West Texas, while lower rates (blue shades) are found in parts of Central and Northwest Texas. Courtesy of researchers

Drawing from the Texas Department of State Health Services’ collection of hospital discharge records, Walker and Crotty — both assistant professors of geography — are mapping high-prevalence neighborhoods for cardiovascular disease. Their research also analyzes how these neighborhoods vary demographically and geographically.

The American Heart Association projects that by 2035, cardiovascular disease will account for almost $1 trillion in direct health care costs each year.

“Traditionally [with heart disease], the emphasis has been on treatment, but a growing emphasis within the health sciences is on prevention,” said Walker, who is also director of TCU’s Center for Urban Studies. “How do we look at factors within one’s residential environment, or certain behaviors, that might influence high rates of cardiovascular disease?

“Treating someone is expensive,” said Walker. “If you can prevent someone from getting sick to begin with, that has the potential to have significant financial implications on health care costs and also just general public health implications.”

Walker and Crotty published their findings in Applied Geography. The researchers’ results found considerable economic variance in high-hospitalization areas, which included lower-income communities in core cities, rural areas and middle-income areas on the outskirts of large cities.

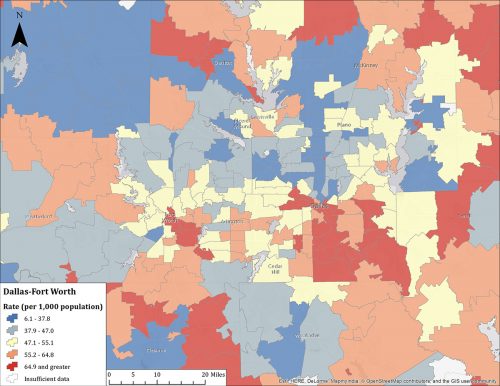

Dallas-Fort Worth Heart Health at a Glance: Applying geographic techniques and analysis to public health research, geography professors Kyle Walker and Sean Crotty are examining the relationships between neighborhood characteristics and social outcomes as they relate to cardiovascular disease. By zooming in on the DFW area, this map gives a more neighborhood-specific view of age-adjusted hospitalization rates for heart disease, based on 2006 hospital records. Courtesy of researchers

“The findings themselves speak to how complicated neighborhood effects can be,” said Crotty, noting that higher income often correlates with better health outcomes. “There are some neighborhoods in Texas, that by any measure would be considered high-income neighborhoods with high education, that also fall into this very high incidence of cardiovascular disease. That’s something that we haven’t seen anywhere else in the literature.”

Down the road, Crotty said the researchers want to go into communities — “particularly the ones that don’t fit what existing literature says should cause higher cardiovascular health problems” — and do more qualitative work to see what is going on.

But the biggest challenge has been wrestling with the enormous amount of data. “We’re working with extremely large data sets. A year’s worth of data has upwards of three million records,” said Walker. “We’ve had to figure out computational approaches — ways to get our computers to work with massive data sets and try to comb through the data to produce insights.”

Walker and Crotty started their research in 2013 with a TCU junior faculty fellowship and a small university grant. The two researchers now are seeking larger grants to extend the project.

“The ultimate goal,” said Crotty, “is to help create policy recommendations for the American Heart Association or Texas Department of Health.”

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related reading:

Research + Discovery

Practice Mindfulness for Less Stress and Better Sleep

Students and faculty go with the flow of meditation and mindfulness.

Campus News: Alma Matters

Yoga for Musicians

Music majors learn to improve focus, build strength and relax.

Research + Discovery

Kristen Carr Studies Coping through Communication

A sympathetic ear can support healing after a stressful event.