Pioneering Treatment

Psychologist Saul Sells showed treatment could cut drug use.

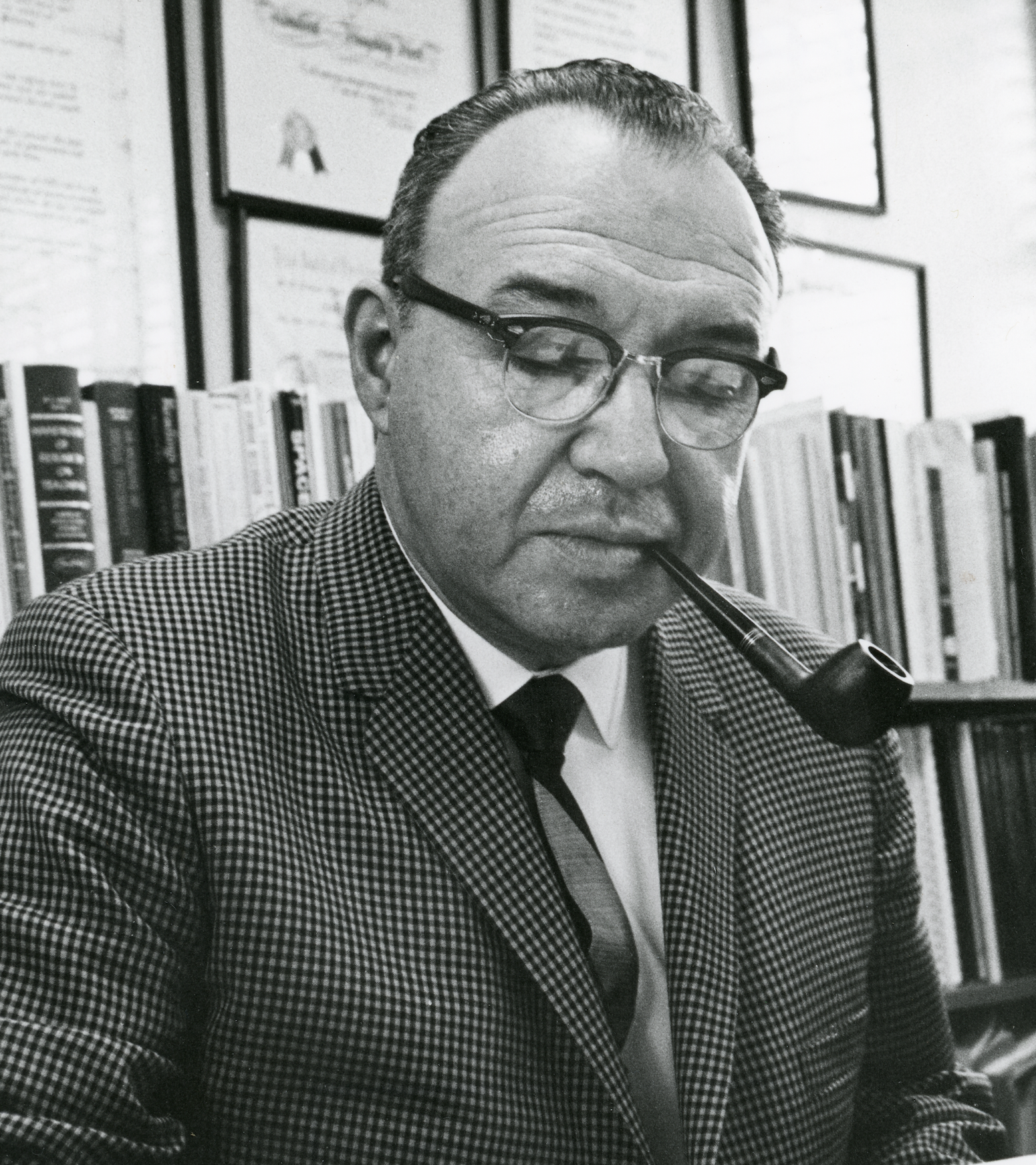

Saul Sells believed that human behavior was a function of many influences, including background, environment and social surroundings. TCU Magazine Photo Collection

Pioneering Treatment

Psychologist Saul Sells showed treatment could cut drug use.

A 1968 TV commercial for Richard Nixon’s presidential campaign begins with ominous music and transitions to Nixon’s warning: “At the current rate, the crimes of violence in America will double by 1972. We cannot accept that kind of future.”

The ad capitalized on the desperation many people felt as drug use and crime, often tied together, had risen through the 1950s and ’60s. The government had been oscillating between treating drug abuse as a disease and sending users to prison. In the late 1960s, nothing seemed to work.

Saul Sells, the founder of TCU’s Institute of Behavioral Research, proved that treatment did work. From 1969 to 1973, he and TCU colleagues surveyed 44,000 people admitted to drug treatment programs — the biggest, most ambitious project of its kind. The results showed that some treatment approaches could lead to rehabilitation.

As a result of those studies, the U.S. government began investing heavily in treatment programs. Today, the federal government spends billions of dollars on drug abuse prevention and treatment efforts.

“The current substance use treatment field has been largely shaped by that early work that Sells did,” said Kevin Knight ’91 PhD, the current director of the institute.

Renaissance Psychologist

A Columbia-trained psychologist, Sells came to believe that human behavior was a function of many influences, including background, environment and social surroundings.

He reasoned that results from a lab study wouldn’t necessarily apply in everyday life, because there were so many environmental variables, said Dwayne Simpson PhD ’70, who directed TCU’s institute after Sells. “He was a scientist who was determined to do research that had real world, practical applications.”

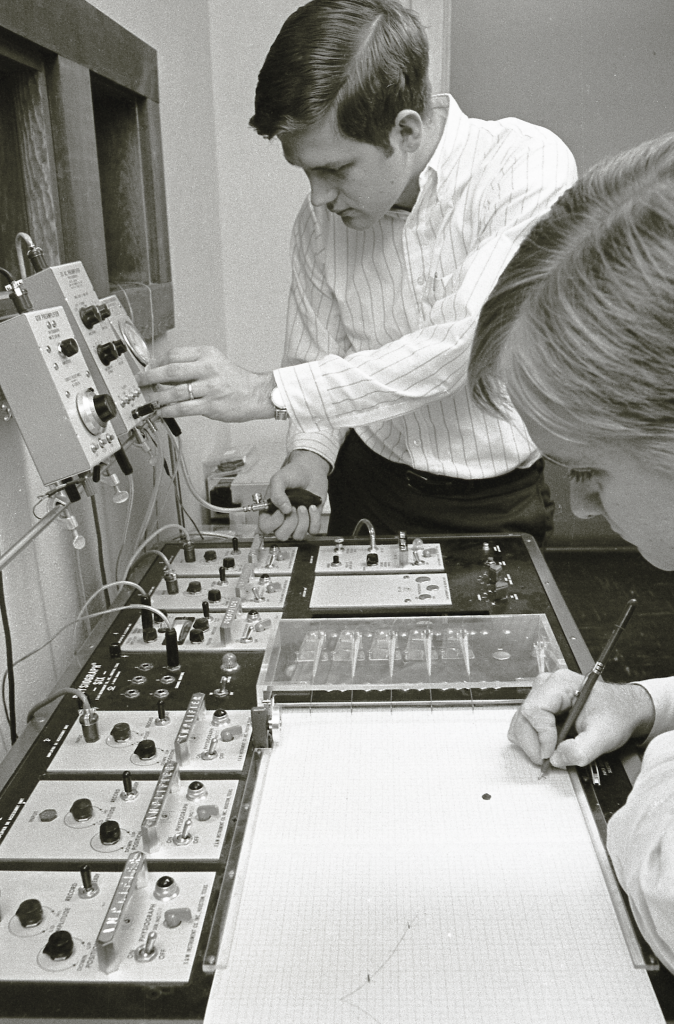

Students in the Institute of Behavioral Research helped Saul Sells undertake a massive project that looked at the success of drug treatment. TCU Magazine Photo Collection

After working as a government statistician during World War II, Sells led the department of medical psychology at the U.S. Air Force School of Aviation Medicine. There, he tested pilots during their training and compared the results with how they performed during combat in the Korean War. His research helped the Air Force select the top pilots.

The mathematical models he developed included multiple data points — demographic information, personality factors, scores on skills tests — and information about the situations pilots encountered in combat. The models were too complex for hand calculation, so Sells ran them through enormous mainframe computers that used punch cards.

Sells joined the psychology department at TCU in 1958 and started the Institute of Behavioral Research four years later. There, he developed analyses to help airlines hire pilots and NASA choose astronauts.

Sells’ colleagues at TCU said he was formal and serious but had a dry sense of humor. He preferred to edit students’ papers with the author sitting in his office, watching silently as he marked through passages and wrote notes.

A Billion-Dollar Question

In 1968, the National Institute of Mental Health tabbed Sells and his institute to assess whether drug treatment was effective. That year, Congress passed the Alcoholic and Narcotic Addict Rehabilitation Act to fund community-based treatment programs. These programs would treat people where they lived, which advocates hoped would reduce the relapse rate — about 70 percent in the two existing federal rehabilitation hospitals.

Sells began by classifying the community treatment programs into four categories: short-term detox; long-term methadone maintenance; outpatient treatment, primarily counseling; and long-term residential therapeutic communities. The psychologists organized data about the 44,000 people participating in treatment. They followed up with 80 percent of those people after they completed their program to measure longer-term success.

His study, formally called the National Drug Abuse Reporting Program, found that, with the exception of short-term detox programs, treatment could work; the longer someone was in treatment, the more successful the treatment was.

Studies led by Sells and others at the institute “demonstrated over time that treatment led to substantial reductions in drug use and crime,” said Barry Brown, a clinical psychologist who worked with Sells as a leader in the National Institute on Drug Abuse. This proved “that an investment in drug abuse treatment was a very worthwhile thing to do.”

A Profound Legacy

In 1983, Sells turned 70 and retired from TCU, and the Institute of Behavioral Research temporarily dissolved. Simpson had been invited to launch a similar program at Texas A&M University. In 1989, TCU invited Simpson and his team back to reestablish the institute.

Psychology experts at the institute have continued to research public health and safety. Much of their work focuses on the criminal justice system and its programs for people with substance use problems.

Under Patrick Flynn, director from 2009 to 2020, scientists studied substance use and HIV services among adolescents in juvenile justice systems. The institute also tested a program designed to help HIV-positive adults who had been incarcerated stay on antiretroviral medication after their release.

Assessment tools such as the TCU Drug Screen are today serving as useful guides across the country for identifying individuals who need treatment and tracking their progress. Sells died in 1988. He had shaped the fields of psychology and drug treatment.

“His impact was about the research making a difference in the real world,” said Knight, formally TCU’s Saul B. Sells Endowed Chair of Psychology. “And he did so at a scale that received a lot of national recognition within the scientific community, in addition to the community impact.”

Your comments are welcome

3 Comments

One of my most memorable experiences at TCU (1959 or 1960) was Dr.Sells personal encouragement. That conversation is somehow still vivid. Cyndy Macnider Roomy

In 1976, I began work on my psychology doctorate and eventually I landed a fellowship at the IBR. Dr. Sells designed the IBR as a model for training applied psychologists. Prior to joining the TCU Psychology Department, Sells had a background in applied research for the Defense Department (Air Force and Navy especially), the Department of Transportation (Federal Aviation Administration), and the Department of Health and Human Services (National Institute on Drug Abuse). Doubtless due to Sells’s influence, I wound up working in all three federal departments at one time or another during my career. In fact, Dr. Sells was an influence, directly or by reputation, in every position I ever held.

As the founding editor of the journal “Multivariate Behavioral Research,” Sells also made TCU a leader in the field of applied multivariate measurement and analysis. IBR training heavily emphasized student mastery in applying cutting-edge statistical techniques. He saw to it that IBR students were involved in the design of organizational surveys, participated in on-site data collection, conducted data analysis, drafted reports, and even sat in on client briefings. That OJT helped us learn how to present findings in ways that top executives could immediately apply to improve the performance of their organizations.

During my career (32 years of which was as a Navy officer), I taught at the UT Southwestern Med School in Dallas, managed a community psychology treatment research laboratory in Fort Worth, had numerous leadership positions providing direct support to the Chief of Naval Operations and the Joint Chiefs of Staff at the Pentagon. I even did a 7-year detail to the Clinton White House before joining an IBR classmate, Dr. Bennett Fletcher, at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda during the last 12 years of my career.

During my career both the Navy and NIH regularly loaned me out to various Federal agency directors in the Department of Health and Human Services, the Department of Transportation, and the Office of Personnel Management. While at NIH I had the opportunity to provide direct support to several foreign governments, including serving as NIH liaison to the EU’s Research Council to help them develop a grants program modeled after that of the NIH. Saul Sells and his IBR staff enabled me to have an amazing career. Doubtless Dr. Knight and his team will continue preparing psychologists for exciting and fulfilling careers.

Great article! I was a graduate student in psychology and worked in the IBR on several research projects with the IBR faculty and staff. Dr. Saul Sells and the IBR faculty, especially Dr. Robert Demaree, made it possible for students to develop skills in applied research. When I completed by PhD, I worked as a staff member in the IBR on several projects. These experiences were essential in my preparation for a career in psychology as a teacher and researcher.

I remember a meeting with Dr. Sells to go over his edit of an IBR technical report that I was first author. I remember him going over his edits as I listened to him explained to me how to improve the report and my writing. The session was very valuable in my developing better scientific writing. I grew to understand that a paper can always be improved to make for clearer communication.

Thank you Dr. Sells.

Related reading:

Research + Discovery

Learning to Avoid Risky Behavior

Probationers use an app developed at the Institute of Behavioral Research to model better decision-making.

Features

Someone to Listen

TCU students counsel children and adolescents through a partnership with Fort Worth schools.

Features

Researching the Answers

Bettering the world drives today’s TCU students toward solutions.