Today’s Disciples continue to prize service, inclusion, justice and peace. TCU founders Addison and Randolph Clark were proud members of the Disciples of Christ church. Original art courtesy of TCU Library Special Collections | Engraving by J.C. Buttre | Designed by J.D.C. McFarland

The Promise of a Name

Ties to the Disciples of Christ have steered TCU from the start.

TCU’s middle name, from a historical perspective, is a nod to a North American church launched in the 1800s. Early pre-Civil War believers joined in hopes of transcending societal division and encouraging unity in a fragmented world.

The denomination known today as the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) was the faith tradition of TCU’s founders, Addison and Randolph Clark.

Soon after the Clark brothers established TCU, they gave the school to the Texas Disciples. Throughout the university’s history, its leaders have worked in partnership with the Disciples of Christ, but the denomination has never dictated what TCU could do.

Instead, TCU has been free to choose what to teach, whom to hire and how to manage its money in alignment with the university’s mission and strategic goals.

For much of TCU’s history, a sizable number of students, faculty and staff, as well as its chancellor, were affiliated with the Disciples of Christ. Today, Disciples constitute a small percentage of TCU’s enrollment and of the American population. The university maintains a covenant with the Disciples denomination and is shaped by values that the two entities share: inclusivity, intellectual curiosity, interfaith dialogue and a commitment to justice.

The Founders

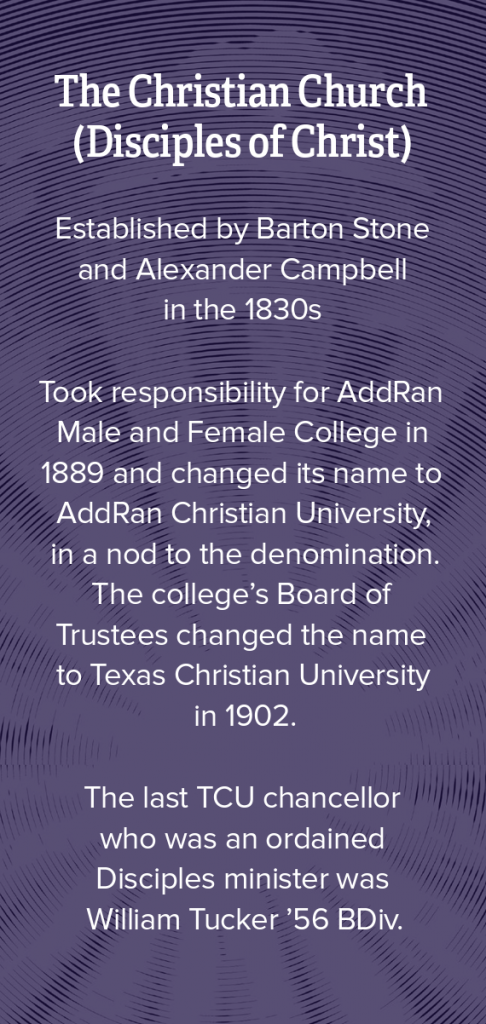

The Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) is a faith born on American soil. It arose from the merger of two 19th-century religious reform movements.

Barton Stone was inspired by the interdenominational fellowship he experienced at Tennessee revivals in the late 1700s. He and his followers hoped this spirit of unity could overcome sectarian divisions. Alexander Campbell of Pennsylvania wanted to emulate the early Christian church by emphasizing charity toward the poor and weekly observance of the Lord’s Supper. His movement was known as the Disciples, or learners.

The Rev. Chalmers McPherson, left, a Disciples of Christ minister, became a trustee of AddRan Male and Female College in 1884. He was instrumental in deciding to move TCU to Fort Worth from Waco in 1910. He became head of Brite College of the Bible after it was established in 1914. Here he is pictured with two other Disciples ministers in 1891. Courtesy of TCU Library Special Collections

In 1832, the groups joined forces. What came to be called the Stone-Campbell movement grew to an estimated 200,000 followers by the Civil War.

Campbell and Stone were educated — relatively rare for their time. They wanted both clergy and congregants to have the same opportunity for higher learning. In 1840, Campbell founded Bethany College in what is now West Virginia. He wanted to offer students from all religious backgrounds a classical education alongside study of the Bible. As the Stone-Campbell movement followed the frontier westward, its adherents established more schools. Disciples colleges emphasized reason, critical thinking and the liberal arts in addition to Scripture.

Unlike religious groups that felt threatened by science, Disciples tended to see faith and reason as complementary.

In Disciples’ view, “faith is not meant to either defeat or be defeated by the wisdom of the world,” said Tom Plumbley ’76, senior minister at First Christian Church, the Disciples of Christ church in downtown Fort Worth. “Rather, faith is meant to grow, and to grow because of its interaction with what God is doing everywhere and in everything.”

Addison and Randolph Clark, born in the 1840s, were raised in the burgeoning Christian Church and attended a school founded by a Bethany graduate.

When they launched a school in 1873, the brothers used Campbell’s model as inspiration. Its charter said that the school would promote literary and scientific education and be open to all students without regard to religious background.

The Clarks established AddRan Male and Female College as a private, family-run enterprise, though its connection to the Disciples was recognized from the beginning.

In its early years, the school struggled with construction debt, increased competition from new universities and a financial model that emphasized affordability at the expense of the institution’s sustainability. The college needed an endowment, and the Clark brothers saw the church as best positioned to provide fiscal stability.

In 1889, the Clarks donated their university to the Disciples, and it became known as AddRan Christian University. Thirteen years later, the school’s board changed its name to Texas Christian University.

“While we’re not governed by the denomination itself, we are intentionally in partnership with them. We are mindful of their values and what that means for us as an institution.”

Todd Boling, university chaplain

From Clarks to Covenant

When the Clark brothers gave their college to the church, the Disciples incorporated it as an independent entity governed by a board of trustees. The arrangement continues in the 21st century.

“The Disciples and TCU have that agreement that, while we’re not governed by the denomination itself, we are intentionally in partnership with them,” said Todd Boling, university chaplain. “We are mindful of their values and what that means for us as an institution.”

The university currently operates under a covenant offered in 2011 by the church to its 15 colleges and universities, which explains the relationship between the schools and the church:

“Each Disciples college and university is characterized by its own integrity, self-governance, authority, rights and responsibilities. … Consistent with Disciples’ identity as a movement for wholeness in a fragmented world, our colleges and universities model the welcoming table through their nonsectarian approach to learning and teaching.

“The core values of a liberal arts education are shared by the church: valuing the dignity of all people, acting with integrity and responsibility, viewing self as part of community, living life within a global context, providing service to others and pursuing lifelong learning.”

“The core values of a liberal arts education are shared by the church: valuing the dignity of all people, acting with integrity and responsibility, viewing self as part of community, living life within a global context, providing service to others and pursuing lifelong learning.”

TCU took the same covenantal approach when it established Brite College of the Bible, later Brite Divinity School, in 1914.

The university had wanted to establish a separate Bible college since the 1890s, and a donation from Marfa, Texas, rancher L.C. Brite finally made it possible.

TCU Chancellor Victor J. Boschini, Jr., who serves on Brite’s board, describes the two institutions as having a sibling relationship that ebbs and flows. “Sometimes there are really intense debates,” he said. “But in the end, we’re still part of the same family.”

Emphasis on Ethics

The covenant with the Disciples continues to shape today’s TCU experience. The denomination’s values are echoed in TCU’s mission statement — “to educate individuals to think and act as ethical leaders and responsible citizens in the global community” — and visible in the university’s emphasis on connection culture.

TCU’s core curriculum requires that all students take a course in religious traditions; classes include World Religions, the Bible, Christian Ethics, Buddhism and Native American Religions. This interfaith approach is central to Disciples theology, said Lea McCracken ’00, associate chaplain and church relations officer. She quoted Andy Mangum ’98 MDiv, regional minister and president of the Disciples Southwest region, who said the church does not have a “copyright on truth.”

“We’re always searching for truth,” McCracken said. “We want to be in dialogue and in conversation with those that are also on that journey of searching.”

When McCracken and Boling lead prayers before football games and other events, they use language that is inclusive and accessible to people from multiple faith backgrounds. “We’re mindful of how we pray, that we’re praying on behalf of people who believe a variety of things,” Boling said. “We pray in a way that everyone can access that prayer where they are.”

Self-Determination

The 2011 covenant articulates ways that churches and universities can best support the partnership. For universities, these steps include actively recruiting and financially supporting Disciples students and identifying and nurturing future leaders for church and society. Part of the process is to “engage in ongoing dialogue on the meaning of [universities’] partnership with the church.”

This dialogue becomes more complex as the number of Disciples students, faculty and staff at TCU declines. This shrinking number reflects the contraction of the overall church, which, like other mainline Protestant denominations, has steadily fallen in membership since the 1960s.

Today the church, which once ranked among the largest religious groups in the country, counts just over 500,000 members. TCU’s Trustees no longer expect to hire a chancellor who is an ordained Disciples minister and leader in the movement; Boschini is Roman Catholic, and his predecessor, Michael Ferrari, was Episcopalian.

In another demographic shift, Roman Catholic students are now the largest religious group on campus, making up nearly a fifth of the undergraduate population. Although Disciples on Campus is an active student group, the number of Disciples students at TCU has declined to less than 2 percent of the student population in 2023.

These days, students may come to TCU with no previous exposure to the denomination.

“Most of my friends who aren’t Disciples don’t know, or didn’t know before meeting me, that TCU was a Disciples university,” said Ella Johnson, a senior religion and political science major and a past president of Disciples on Campus. “Once they’ve learned that, they don’t know what Disciples of Christ is.”

Disciples ministers interviewed for this story said that some people unfamiliar with the denomination may associate “Christian” with a political expression of Christianity far removed from Disciples’ emphasis on inclusivity, coexistence and ecological sustainability.

“The Disciples denomination has done great work, and our job is to continue to do that great work. Regardless of what the future of the denomination looks like, the legacy of what it has accomplished is woven into the fiber of the university.”

Lea McCracken, university assistant chaplain and church relations officer

Thus students are likely to continue debating the nature of a Christian university in class and in student media.

Those conversations are healthy and constructive, Boschini said.

“I think if we stopped having that discussion, it would mean people don’t care about these issues,” he said. “I think it’s good that we’re having the exact same conversations we were having 20 years ago about: What does the ‘C’ mean? Because I think every kid that comes here ought to determine that for themselves.”

The shrinking size of the Disciples church is not the only religious phenomenon shaping the future of TCU. In the past two decades, the number of young people not affiliated with any religion has increased sharply. About 45 percent of today’s TCU students have not identified with a particular faith.

McCracken said these trends portend significant changes in American Christian practice.

“In the next 20 years, church in general and denominationalism are going to look very different,” she said. “And Disciples is going to look very different.”

She and Boling said that even without many Disciples in the student body or university leadership, TCU’s Disciples heritage will still be evident. It will manifest, they said, in the shared values of the church and TCU that shape the academic and extracurricular experience: critical thinking, justice, interreligious dialogue and unity even in the face of disagreement.

“The Disciples denomination has done great work, and our job is to continue to do that great work,” McCracken said. “Regardless of what the future of the denomination looks like, the legacy of what it has accomplished is woven into the fiber of the university.”

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related reading:

Features

Forgotten No More

TCU’s Race & Reconciliation Initiative shows the promise of the future through a face from the past.

Features

A Dream and a Prayer

Addison and Randolph Clark’s tiny coed Christian college on the prairie blossomed into TCU.

Alumni

Behind the Names

Two Burnett women have shaped TCU’s past, present and future.