In Deep Water

Environmental expert Becky Johnson forecasts the flow of water pipeline dollars into communities.

Installation of the 150-mile Integrated Pipeline began in 2014. (photo courtesy of the Tarrant Regional Water District)

In Deep Water

Environmental expert Becky Johnson forecasts the flow of water pipeline dollars into communities.

Becky Johnson ripped out the grass in her backyard and replaced it with artificial turf to conserve water. After working for more than two decades as an environmental consultant, she understands the severity of water scarcity.

“People don’t think about where water comes from,” said Johnson, professor of professional practice in environmental science. “They turn on their tap, and they expect it to be there.”

But the Earth’s potable water is limited, and delivering it to urban areas is becoming more complicated. In North Texas, water demands are surging to levels the current supply cannot sustain. In the next 40 years, the population in the Dallas-Fort Worth area is expected to double to more than 13 million people. Without aggressive expansion of water sources, what comes out of faucets will slow to a trickle.

To address the problem, the Tarrant Regional Water District and Dallas Water Utilities teamed to tap additional water resources in East Texas and build the 150-mile Integrated Pipeline to serve North Texas homes and businesses until at least 2060.

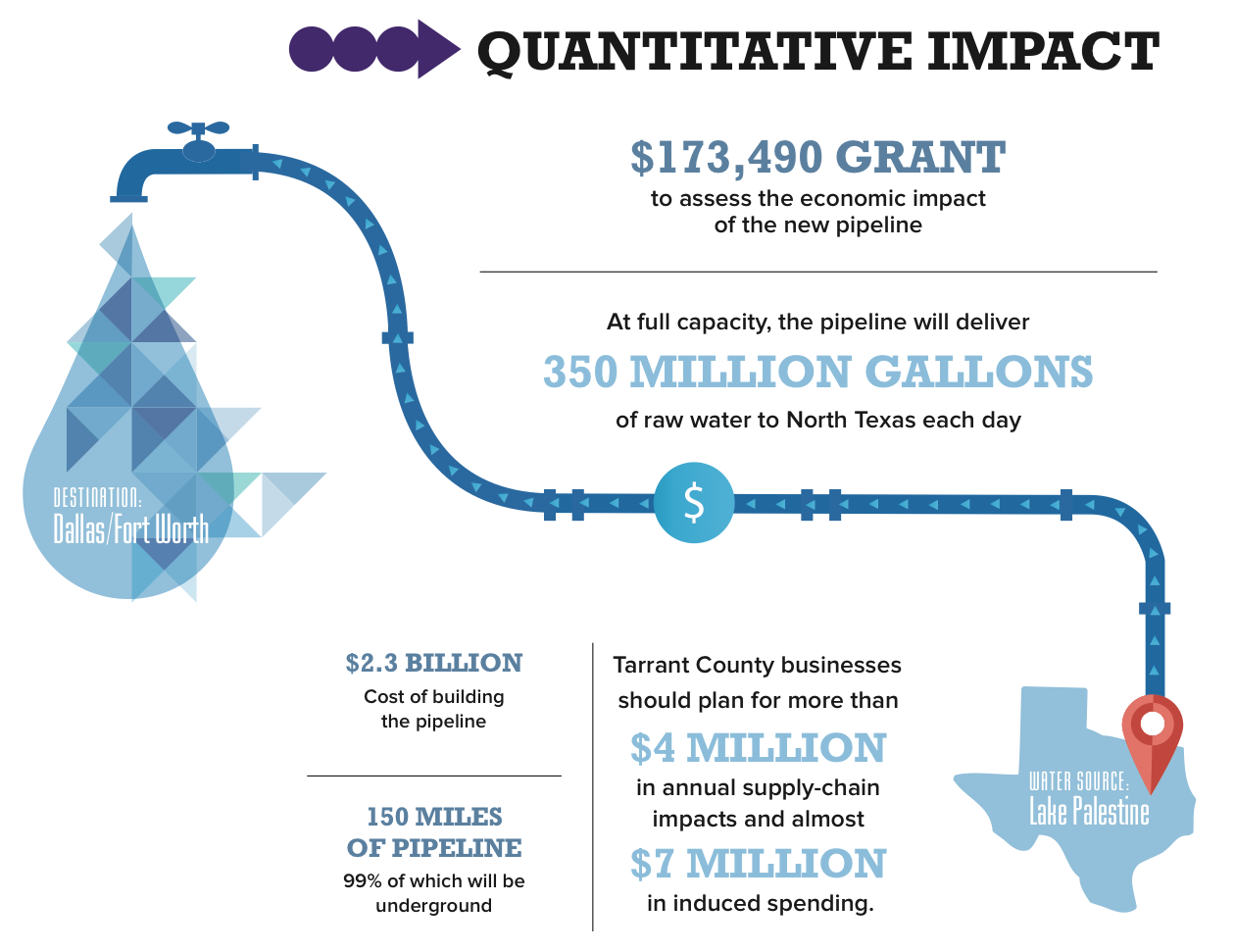

During the 20-year installation period for the $2.3 billion pipeline, construction will flow through six counties, bringing a temporary water-fueled economic boom. How much extra income can each county expect to gain? The regional water district awarded Johnson a $173,490 grant to run a comprehensive economic impact analysis to find out.

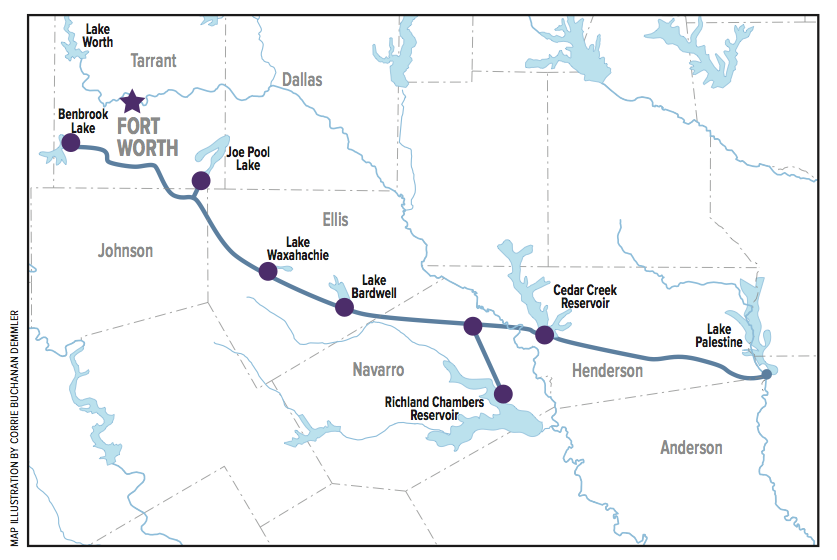

The Integrated Pipeline will deliver about 350 million gallons of water daily to North Texas. The purple dots represent pump stations that will move water from Lake Palestine to Lake Benbrook.

Oil and water

In 1985, Johnson had just received a bachelor’s degree in geology and was looking for work in the oil industry. Low crude prices meant few job opportunities. The environmental realm, however, was new and hiring. Johnson earned a master’s degree in environmental science to help launch a career specializing in soil and groundwater contamination cleanup. In managing numerous projects, she learned the intricate budgetary details of complex environmental undertakings.

Becky Johnson, professor of professional practice in environmental science. (photo by Carolyn Cruz)

TCU recruited Johnson from the industry to bolster classroom environmental theory with professional reality. She teaches groundwater hydrology, environmental compliance and environmental impact statements. When she tackles outside research projects, such as the pipeline analysis, she includes students so the aspiring environmental scientists benefit from practicing problem-solving and gain an insider look into the industry.

“In school, we get a little too hypothetical. We forget how [environmental theory] actually applies to real-world scenarios,” said Emily Ritter, who managed the seven-student team tackling the pipeline analysis before completing a master’s degree in environmental science in 2015.

Although running multifaceted economic models isn’t part of Johnson’s usual work, she gained experience by collaborating with Michael Slattery, director of the Institute of Environmental Studies and professor of environmental sciences. Johnson and Slattery have worked together since 2008 on the TCU-Oxford NextEra Wind Energy Research Initiative, for which she conducted a socioeconomic impact analysis.

Johnson’s familiarity with environmental economics led to the water district project. The nearly 100-year-old regional water district provides raw water to 98 percent of the residents in Tarrant County, which includes Fort Worth. About 80 percent of its water supply originates from the nearby Richland-Chambers and Cedar Creek reservoirs.

“We are actively finding ways to get more water back to the people who depend on it here in Tarrant County,” said Chad Lorance, a spokesperson for the water district.

Dallas Water Utilities has a contract to use the water in Lake Palestine in East Texas, which was created as a future water supply reservoir in 1965, although it has yet to be tapped for its intended purpose. The regional water district needed to expand its ability to pump water from the two existing reservoirs. So to achieve both objectives, save money and reduce the environmental impact, Dallas partnered with the Tarrant water agency to build the 150 miles of pipeline, 99 percent of which will be underground. Construction crews broke ground in 2014. At full capacity, the pipeline will deliver 350 million gallons of raw water, the equivalent of 530 Olympic-size pools, daily to North Texas.

Population on the rise

For the pipeline impact project, Johnson teamed with Bernard Weinstein, associate director of the Maguire Energy Institute at Southern Methodist University. His portion of the project plotted expected population growth against current water availability. Weinstein predicted water demand would grow almost as quickly as the area’s anticipated population. Without expanding the water supply, Weinstein found that the Dallas-Fort Worth area could suffer an estimated $6 billion economic fallout as soon as 2020.

Water sales revenue and $440 million in low-interest loans from the Texas Water Development Board will pay for the pipeline project. Much of the investment will spin off to areas east of Fort Worth and Dallas, stimulating the economies of the counties whose dirt is being disturbed.

“The whole intent was to go in and say, ‘Look, construction is going to be in your county for the next two years. Here are the kinds of industries that are going to be impacted the most, and here’s how you can take advantage of it.”

Becky Johnson

Johnson and her students quantified those economic benefits on a county-by-county basis. “The whole intent was to go in and say, ‘Look, construction is going to be in your county for the next two years. Here are the kinds of industries that are going to be impacted the most, and here’s how you can take advantage of it,’” Johnson said.

On Slattery’s wind energy project, Johnson used software dubbed JEDI, for Jobs and Economic Development Impacts, to model the monetary influence on four counties in arid West Texas. The development impact software is the “little brother” of IMPLAN, or Impact Analysis for Planning, a master spreadsheet used for the larger pipeline project.

Data Droplets

After a three-day software training session, Johnson and her students tested the pipeline economic impact model with random inputs and compared fictitious results during weekly meetings. “We had two different teams, and they would run the model and see if both teams got the same answers,” said project manager Ritter.

“Little details can throw off the results significantly. So we were figuring out where the program was sensitive,” Ritter said. “After that, our results ended up being consistent throughout, using the actual data.”

It was a valuable “step-by-step problem-solving experience,” said Nick Haber, the lone undergraduate student to work on the pipeline project for its duration.

When Johnson’s project team tackled the complex projections for the water pipeline, they asked questions. For example, does Navarro County have sand and gravel pits available for making concrete? Where is the closest place to Ennis, Texas, to rent 20 backhoes? Where will the construction workers live for the 83 months they spend in Henderson County?

Johnson said supplies purchased in one county would filter through other project segments differently. “In Tarrant County, there’s a big concrete water pipe manufacturer, so that money would propagate through the county very differently than it would propagate, say, through Ellis County, where Ellis County may have the sand and gravel pits, or the mines to supply the sand and gravel, to that pipe manufacturer in Tarrant County.”

Tamie Morgan, professor of professional practice in environmental science, provided Johnson’s project team the geographic information system expertise to map the construction route so costs could be apportioned based on tangible data.

After the two student teams ran the figures forward and backward until they arrived at identical outcomes, Johnson had numbers to share with the regional water district.

Filling wallets

The economic analysis divided the pipeline project’s impacts into three categories. First, total direct impacts, or actual construction-related costs, should generate the most economic activity, including more than $100 million each year in wages.

Second, indirect impacts involve supply-chain purchases, such as backhoes and welding supplies, and secondary employment increases. Using these forecasts, businesses along the pipeline route can prepare for the big customer headed their way.

Last, induced impacts show how unrelated industries in each area will prosper. “You’ve got all these extra people working in your county, and they’re buying more gasoline at the local store,” Johnson said. Gas stations, restaurants, hospitals and housing services should get prepared for the anticipated economic influx, too.

Armed with Johnson’s economic impact analysis, people in the counties involved in the pipeline project can strategize for the incoming economic activity. For example, Anderson County, which contains Palestine, can expect an additional 146 jobs each year for the 71-month duration of construction in the county as well as more than $4 million in induced annual spending. Tarrant County businesses should plan for more than $4 million in annual supply-chain impacts and almost $7 million in induced spending. (Dallas County will not see actual pipeline construction but will receive income related to pipeline planning and management.)

In aggregate, according to Johnson’s analysis, the pipeline project should generate a slight economic benefit, not including the expanded water supply. “The overall impact is a little bit more than the cost of the pipeline,” Johnson said. “But it’s having a pretty big ripple effect.”

Water shortages ahead

North Texans can rely on Lake Palestine to help provide sufficient water until 2060. But Johnson said the Integrated Pipeline is a temporary fix. “This was all prairie,” she said. “This landscape was never meant to support the number of people that it’s supporting in terms of water.”

Agriculture uses about 70 percent of the water consumed, and farmers can innovate, but they can conserve only so much. Municipal use swallows 20 percent of the total, and “about 40 percent of that is outdoor watering,” said Johnson, who gave up her backyard of St. Augustine grass.

Water shortages will be the defining issue of the future, Johnson said. “Historically as a nation, we have not had to pay much of a price [for water],” she added. “I think given our population, that time is over, and the price to be paid is coming, and it’s coming quickly. I’m not sure people are ready for it.”

Construction of the $2.3 billion Integrated Pipeline will deliver monetary benefits in addition to badly needed water

Your comments are welcome

1 Comment

Lake Palestine full pool level is 345’. How many feet below 345’ will be the considered the stop point in order to conserve the viability of the lake Palestine?

2022 summer season levels left most boats with dry land under them. Does your study consider water pull cutoff lake levels and or notifications to waterfront residents so boats can be trailered before they are stranded?

Related reading:

Features

Politics 101

Students appraise the political landscape

Features, Research + Discovery

Leading a Culture Change in Health Care

Faculty at the Harris College of Nursing & Health Sciences are helping fuse research with health care practice.