He sang to me

Gary Blevins ’62 remembers the father who sang to him.

He sang to me

Gary Blevins ’62 remembers the father who sang to him.

When I was a child, my father sang to me while driving the car.

When I was a child, my father sang to me while driving the car.

Among his nonsense ditties was one about a “barefoot-boy-with-shoes-on sitting in the grass.”

Dad never failed to sing that song when he took me to and from stays at my grandmother’s house. He didn’t sing to entertain so much as to exasperate, and he always got a rise out of me: “Hey, would you stop it!” And Dad would lazily respond, “Hay? That’s what horses eat.”

Maybe this performing, if only for his son, predestined the few years Herb Blevins would work as a movies extra. It would also touch my life many years later.

Dad’s acting stint followed my parents’ divorce in Fort Worth when I was 11. Dad drove to Southern California with a Southside “starlet” named Darlene, who soon landed roles as a dancehall girl hanging onto Bob Hope in the “Paleface” pictures.

Did Dad sing for Darlene?

During the years 1950-1951, the letters from California advised me when and where to look for “Tex Price,” my father’s stage name, in a soon-to-be-released movie.

In most of the films, I had to be quick to find Dad hidden in the background. He wasn’t given a singing role, thank God, but he did speak two or three lines in one low-budget racetrack picture. That’s Tex under the grandstand, radio to ear, rooting for the hero’s horse to win the climactic race. He portrayed GIs in several war films, including The Halls of Montezuma, and he had a noteworthy role — all of 30 seconds? — in Humphrey Bogart’s The Enforcer. Dad is one of the two G-men holding Thompson sub-machine guns who ride an elevator with Bogey.

It was assumed that Tex Price knew his way around horses. But after being bitten and trampled a few times working on westerns, Dad took riding lessons at Los Angeles’ Griffith Park. He didn’t become a wrangler like the late Ben Johnson or the venerable Richard Farnsworth, but he faked his riding skills well enough to get work.

An extra’s life was “interesting and fun,” but Dad eventually realized that age and a late start were against him. Even if he did have Tyrone Power-Henry Fonda good looks (Don’t all kids think their parents are the best looking, the smartest, or the most fun?), it was time to find a real job. He ended Tex Price’s “career” the day an assistant director offered him a lift home after a shoot . . . and casually placed a hand on Dad’s thigh during the ride.

“I wanted to work in the movies, but I didn’t want it that badly,” he once said.

When I began spending summers with Dad in 1952, he was working for McDonnell-Douglas Aircraft in Santa Monica. He had remarried, although he said dropping Starlet Darlene wasn’t as easy as dropping Tex Price.

“I tried to ease out of that relationship,” Dad explained some 40 years later. “She got too wild for me, and I was trying to live a normal life. She finally got the message when I began changing the routes I used leaving the plant.”

One day Dad left work and found every window in his car smashed.

“Darlene’s reaction to my avoiding her hurt doubly because the car wasn’t mine,” Dad laughed. “It was my sister’s car!”

My mother, Eileen, also remarried, and I continued to live in Fort Worth and eventually graduate from TCU. But I spent parts or all of some 10 summers with Dad and my stepmom Judy in California: camping trips to Sequoia and Yosemite, long days on shoots at Corrigan Ranch and the MGM Studio, outings to Knott’s Berry Farm and Disneyland and seeing famous actors on the street and in their cars — Roy Rogers pulled up beside us not riding Trigger, but driving a Jaguar convertible.

Dad and I shared an exciting moment once when a red light saved us from being trapped when a hillside collapsed onto the Pacific Coast Highway. Three cars in front of us were buried, and among oceanfront residents coming to aid the victims were Burt Lancaster and Peter Lawford. By 1986, Dad had retired from McDonnell-Douglas.

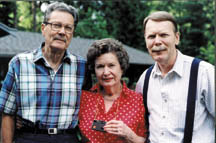

He returned to Fort Worth for his 50th reunion at Paschal High School, and he was alone. (Judy died in 1984, and my stepfather, Billy Joe Orren, had died in 1977.) Mother and Dad saw and spoke to each other for the first time in 36 years. My still-handsome parents hit it off so well that Dad sold his California house and joined Mother in her Meadowbrook-area home.

My parents traveled in Dad’s RV for about six years. They visited me and my wife JoAnne in the Seattle area four times. Dad continued to maintain the muscular, 190-pound body that served him as a deep-sea-diving Seabee during World War II. Alzheimer’s symptoms began to appear about 1990.

On a trip to Washington State, he asked Mother if she noticed all the Oregon license plates on the road around them. “Well, Herb,” she replied, “We are in Oregon.” While Mother could trust him to drive, Dad often forgot where he was going. He changed the battery in one of their two cars. The next day he didn’t know which car had the new battery.

Dad became increasingly confused and agitated. He couldn’t remember who was dead and who was living. He forgot Judy. He attended his brother’s funeral and asked Mother as she drove them home, “Now where have we been?”

He repeated the same questions again and again, every day. Dad forgot “those people who live in Seattle,” his son and the daughter-in-law he said was “nicer than an in-law.”

But he seemed to remember us when we visited the Old Folks at Home in Fort Worth. I wondered if he had saved his best acting job until the end, but as confused as he was, he welcomed us lovingly.

A man who was fastidious in his dress and grooming eventually stopped getting his hair cut. He no longer shaved. When Herb Blevins died on May 26, he weighed 150 pounds. Instead of projecting a Tyrone Power look, he resembled an unkempt Howard Hughes. He didn’t speak. He knew no one. And he was unaware that a tradition was continuing.

A man who was fastidious in his dress and grooming eventually stopped getting his hair cut. He no longer shaved. When Herb Blevins died on May 26, he weighed 150 pounds. Instead of projecting a Tyrone Power look, he resembled an unkempt Howard Hughes. He didn’t speak. He knew no one. And he was unaware that a tradition was continuing.

Our five granddaughters will tell you that I have sung to them all of their lives . . . in the car and on the hiking trail. They sometimes get exasperated with their “Pappy’s” singing. But when I’m hitting the right notes, they usually join in: “When I get to Heaven . . . tie me to a tree . . . Or I’ll begin to roam — and soon you know where I will be.”

Gary Blevins lives in Woodinville, a suburb of Seattle, Wash. He is a writer/editor with The Boeing Company in Renton. He and wife JoAnne have two sons and five granddaughters, all of whom live in Fort Worth. Gary says he flies the granddaughters to Seattle often.

Your comments are welcome

Comments

Related Reading:

Alumni

Horned Frog Foodies: Molly Wilkinson

From her home in Versailles, France, the alumna shares her love of baking with the world.

Alumni

Guy “Sonny” Gibbs, TCU Quarterback Legend and Hall of Famer Who Toppled No. 1 Texas, Dies at 85

The “Graham Giant” spent six decades as one of TCU’s most beloved figures, on the field and far beyond it.